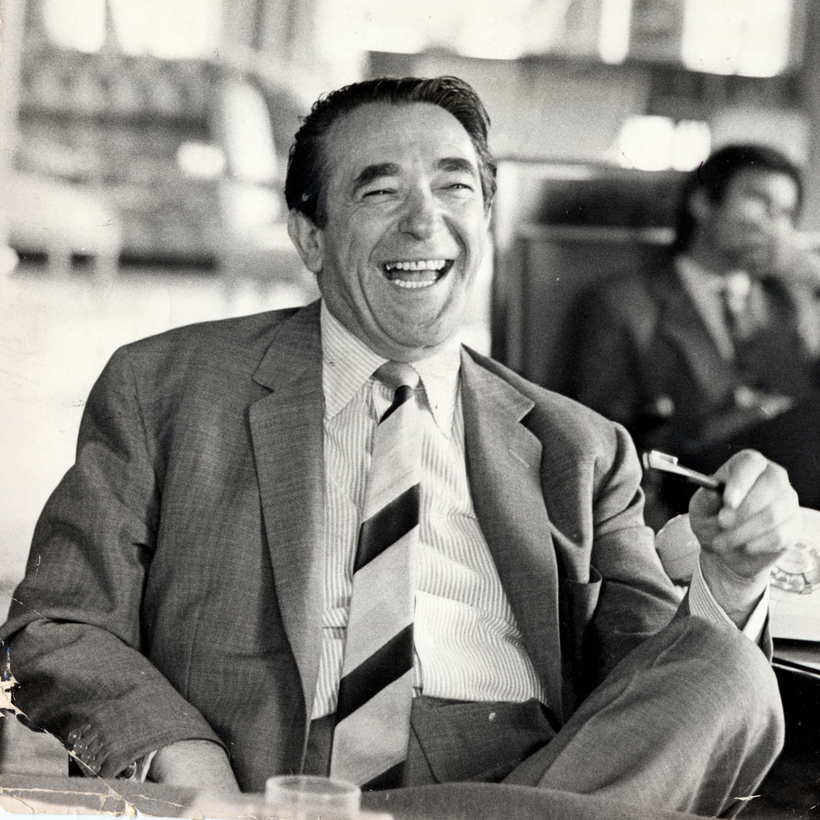

Walking into Robert Maxwell’s bedroom late one night, his son Ian was surprised to see the tycoon bending down with his nose almost touching the glass of his enormous television. On the screen was a documentary showing newsreel footage of Jews arriving at Auschwitz on trains and then being divided into two groups – those deemed fit for work and those who were to be sent straight to the gas chambers.

‘What are you doing?’ his son asked.