Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present by Ruth Ben-Ghiat

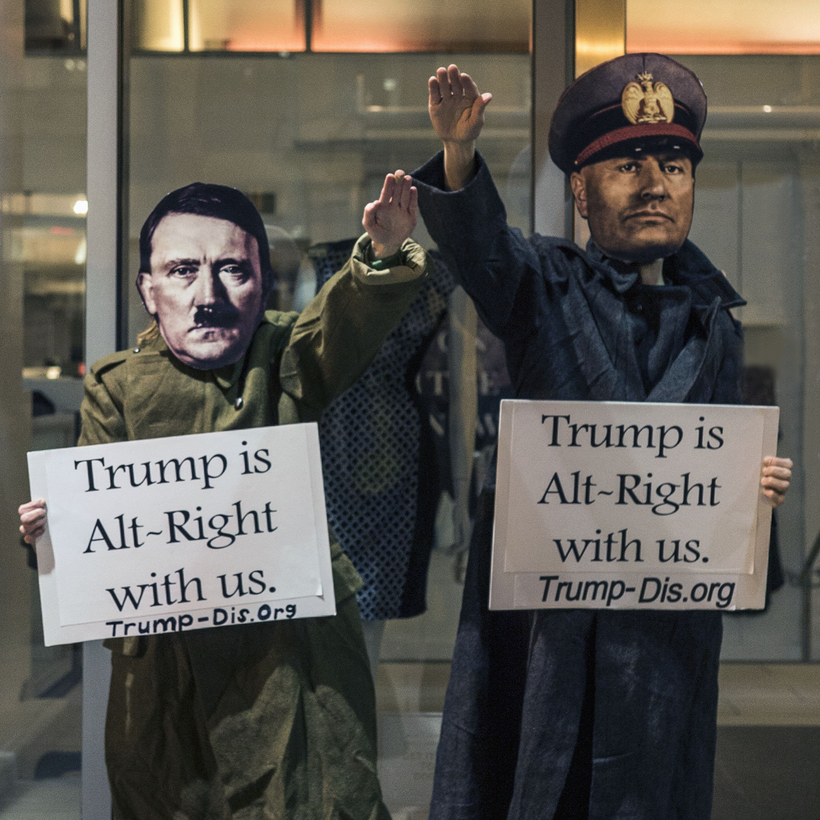

Since the day in 2015 when Donald Trump rode down the Trump Tower escalator and started blaming “Mexican rapists” for national problems—and then sent his ex-N.Y.P.D. private-security goon onto Fifth Avenue to beat those who protested—people have been comparing him to Adolf Hitler. And in the more than five years since Trump launched his appeal to white identity, the Trump-Hitler comparisons have only grown louder and more common, from social-media memes to op-eds.

They are not wrong: one can simply go back and watch his rally performances in black and white with the sound down to be reminded of 1930s Germany. But, critical as it is of the president, the mainstream media has been reluctant to go full-on Adolf when covering Trump.