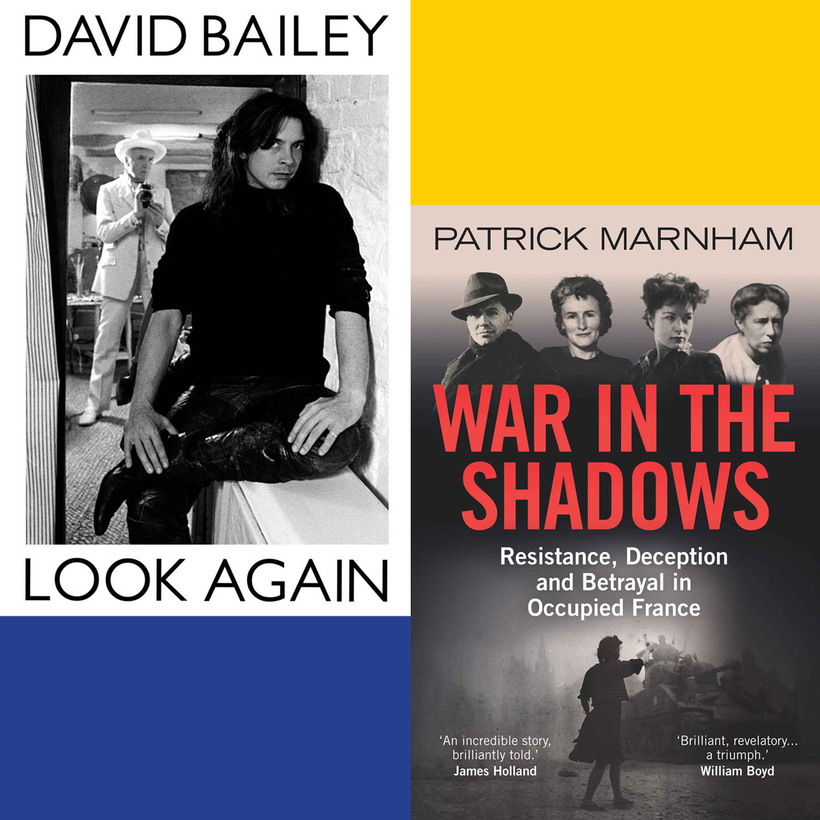

Photography, said David Bailey, is sex. He made it that way.

The man who styled the 1960s, changing the way we looked at women and helping to create celebrity culture, was a shameless priapic who thought nothing of a quick one in the studio with almost every model he worked with. He was married to, or lived with, some of the most beautiful women in the world — Jean Shrimpton, Catherine Deneuve, Penelope Tree, Marie Helvin — but was incapable of being faithful. Often he had three girlfriends at the same time. From the age of 14, Bailey was a hard-drinking tough nut from London’s East End, and his chat-up line at dances was: “Do you want to f***?”