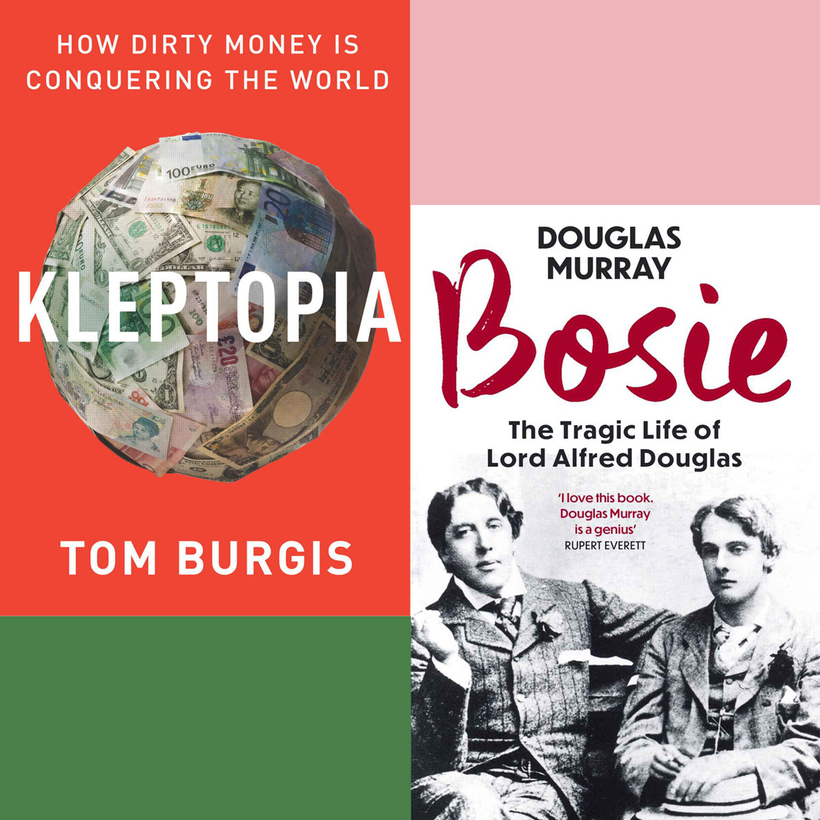

Taste in physical beauty evidently changes over time. Oscar Wilde rhapsodized about his lover Lord Alfred Douglas’s “slim gilt soul”, cried out for “those red rose-leaf lips of yours” and said he was “gold-haired like an angel”. Yet in photographs Bosie rather resembles Stan Laurel or Alec Guinness in a character role. It is the brilliance of this biography to view Bosie’s “tragic life” through a comic prism — he was in Douglas Murray’s words such a “terrible, partially deranged, infuriating person”, the only possible attitude left is laughter.

Bosie’s family, who held the title of the Marquess of Queensberry, for a start, were cartoonish in their grotesquerie. The Douglases were mad, and flying into “fits of rage, gibbering and snarling” was an inherited trait. Cannibalism (one ancestor in 1707 impaled a cook’s boy on a spit and roasted him), dramatic shooting accidents, suicides, explosions and mountaineering mishaps beset the clan. Incest was not unknown. Bosie’s uncle was “deeply attached to his twin sister” and was heartbroken when she married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, known as Sir ABCD. He drank himself into a deep depression. One of Bosie’s aunts kept a pet jaguar, obtained in Patagonia, which annoyed Queen Victoria by killing deer in Windsor Great Park.