I had only been working for Andy Warhol for a year when I found myself at Eothen, Andy’s 30-acre estate overlooking the Atlantic Ocean in Montauk, Long Island, during the delightful summer of 1971.

In August 1969, I was driven to New York City with two friends from my hometown of San Diego, California, and ended up in the back room at Max’s Kansas City, where I met Andy Warhol. He hired me to work full-time in January 1971.

Andy and Paul Morrissey purchased Eothen (Greek for “from the morn, at earliest dawn”) a few months later for $235,000, at a time when Montauk was still a little fishing village. That was all about to change with the arrival of Andy and the seemingly endless stream of artists, rock stars, and other celebrities that followed him wherever he went.

Eothen comprised four individual cottages, a five-bedroom main house, a stable, a three-car garage, and nearly a kilometer of uninterrupted coastline. The compound was built in 1931 for the Church family, heirs to the Arm & Hammer fortune, who used it for two weeks in September when the striped bass were running.

Princess Lee Radziwill was the first to rent the main house in the summer 1972 (Andy believed the property should try to pay for itself). Lee—we always called her Lee, never Princess Radziwill—was having an affair with the photographer Peter Beard. And what an attractive couple they made.

I don’t remember how it was conveyed to me, but it was understood by everyone around Andy, that no one could ever mention the affair, since Lee was in the process of divorcing her second husband, Prince Stanislaw Albrecht Radziwill, the scion of the Polish-Lithuanian princely House of Radziwiłł. The divorce wouldn’t become final until three years later. By then Peter Beard had moved on, but he and Lee remained friends for the rest of their lives.

Lee’s second marriage produced two children, Anthony and Tina Radziwill, aged 13 and 12 in 1972, who played with their cousins, John-John and Carolyn Kennedy, whenever Lee’s sister, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, came to visit. Bob Colacello, the editor of Interview magazine, said Andy joked about erecting gold plaques above the Kennedy beds saying, Jackie slept here.

Besides Mrs. Kennedy, there was also Mick and Bianca Jagger, who came to stay with Lee in the main house for rest and relaxation during the Rolling Stones’ 1972 North American tour. That’s when Mick fell in love with Eothen, and also became closer to Peter Beard, whom he had hired, along with Truman Capote, another frequent guest, to join the tour. Peter Beard was the official tour photographer, and Truman the official tour diarist. For security reasons, Peter and Truman were code-named “Peter Radish” and “Trudy,” respectively, although Keith Richards insisted on calling Capote “Truby.”

In the 1950s, Andy had been a huge fan of Truman’s, writing him so many letters that Capote claimed, “When [Andy] came to New York, he used to stand outside my house, just stand out there all day waiting for me to come out. He wanted to become a friend of mine, wanted to speak to me, to talk to me. He nearly drove me crazy.” It was Truman’s mother who convinced Andy to stop stalking her famous son. Eventually, through Lee Radziwill, Andy and Truman became friends.

Andy joked about erecting gold plaques above the Kennedy beds saying, Jackie slept here.

At Eothen, Truman was constantly soused on vodka while the rest of the crowd usually enjoyed a decent rosé from France (not that sweet Mateus Rosé, virtually the only rosé you could find in those days). Though Truman was always marinated, he usually made the drive from Montauk to his home in Sagaponack—in his convertible, with the music blaring—without incident. Of course, Montauk was less populated, but that was about to change—thanks in part to Andy and to the Stones, who would return to Eothen in 1975, using the main house as a rehearsal space.

The talk-show host Dick Cavett was our closest neighbor, and he usually walked on the beach to the edge of Andy’s property and waited until he was invited in, usually by Lee. One day, Fred Hughes, Andy’s business manager, came into Boomhauer Cottage from the beach and urged us to come down. Cavett was standing on the beach, watching the waves, wearing nothing but a cap, a scarf, and shoes. Andy, who turned bright red, was speechless.

On Andy’s 44th birthday, Lee decided to give Andy a flagpole for the compound. Fred, Jed, Paul, and I drove Andy to Herb McCarthy’s in Southampton for lunch to keep him distracted while it was being installed. But our ruse did not succeed. As Andy noted in his diaries, “It was supposed to be a secret, so the first thing Paul [Morrissey] did was tell me about it and tell me that I should act really surprised.”

We made sure the American flag was raised and lowered on most days, which was also a signal to Dick Cavett, notifying him when there was somebody staying at Eothen that he might want to interview for his television program. One of our guests that Cavett “borrowed” to appear on his TV show was Mick Jagger. Cavett went backstage at Madison Square Garden and talked to Jagger moments before the lead singer went out to perform. “If anybody was to see me just before a performance like this, I’d be furious,” Cavett said. “I am furious,” Mick said.” “Really?” Cavett asked, and Mick said, “No, not really.” But was he telling the truth?

Andy was more at ease with the kids at the compound during the 70s, claiming, “I love Mick and Bianca, but Jade [Jagger’s] more my speed. I taught her how to color and she showed me how to play Monopoly. She was four and I was 44. Mick got jealous. He said I was a bad influence because I gave her champagne.”

I was accused of being a bad influence, too, when John-John and Caroline and Anthony and Tina Radziwill convinced me to drive them all into town—undetected—to get ice cream. When I returned from our mission, the Secret Service agents in their Hawaiian shirts were furious, but it was Jackie who reprimanded me, when she called me to the main house. Actually, she was very nice, but very firm, as she explained the dangers of the paparazzi, though none of the kids were recognized in town.

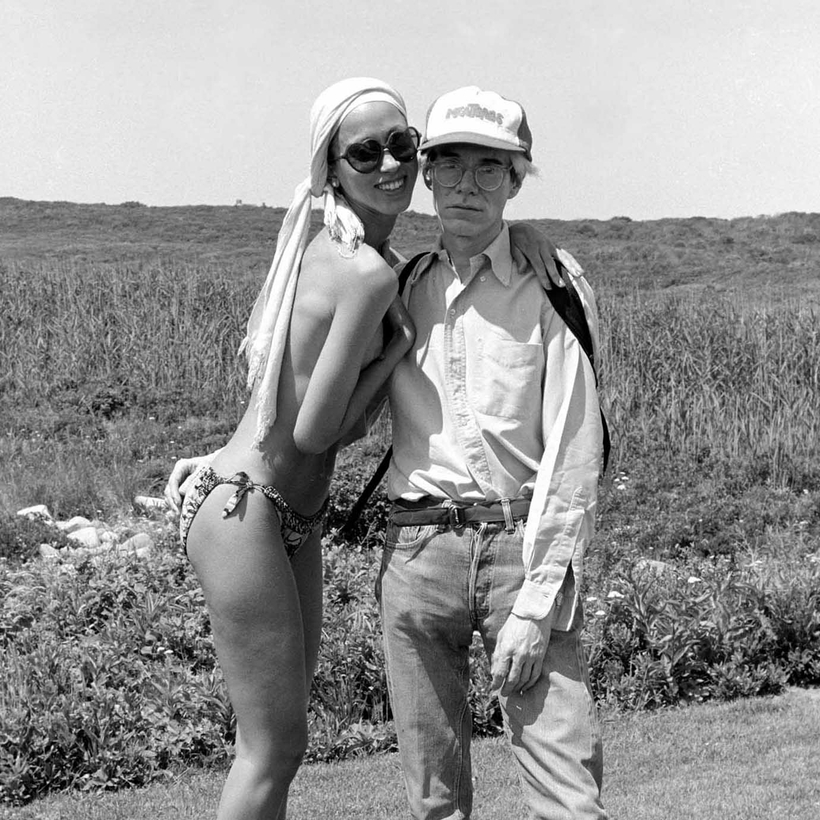

On those boiling August days, when everyone was playing in the surf, Andy would show up on the beach dressed in jeans and a long-sleeved shirt with a hat pulled down tight, protecting his translucent skin from the sun. I never saw him in a bathing suit, ever.

It might’ve been his embarrassment over the scars he received from Valerie Solanas when she shot him in 1968. The bullet went through his spleen, stomach, liver, esophagus, and lungs, leaving him severely wounded. But I believe Andy was simply protecting himself from the sun. “If someone asked me, ‘What’s your problem?,’” Andy was quoted as saying, “I’d have to say, ‘skin.’”

During that magical summer of 1972, Lee Radziwill and Peter Beard had the idea to visit Lee’s aunt, Edith Bouvier Beale, and cousin, Edith “Little Edie” Bouvier Beale, at Grey Gardens, their dilapidated, overgrown mansion in East Hampton. Both Edies were wonderful, eccentric ladies, oblivious to the present, and to their squalid living conditions. Lee and Peter felt the Beales would make fantastic subjects for a documentary. For some reason unknown to me, Lee and Peter’s documentary was never completed, and the footage was lost. But not long afterward, Albert and David Maysles’s Grey Gardens became an unexpected hit, as well as a cottage industry of Broadway plays and an HBO special on Big and Little Edie.

Andy would show up on the beach dressed in jeans and a long-sleeved shirt with a hat pulled down tight, protecting his translucent skin from the sun. I never saw him in a bathing suit, ever.

It was also during that summer that Andy told me he wanted me to learn to use the Sony Portapak, a handheld video camera. It became my job to learn how to operate the equipment, which quite a few artists had been experimenting with. Video was a new, inexpensive way to film people and events, perfect for Andy’s purpose. As Sony’s own video manual confirmed, “The portable video system represents the essence of decentralized media: one person now becomes an entire TV studio, capable of producing a powerful statement.” It also satisfied Andy’s need for instant gratification.

One powerful statement I videotaped during Lee Radziwill’s late-afternoon cocktail parties was Truman Capote explaining why he dropped out of the Rolling Stones’ 1972 North American tour before he completed his assignment for Rolling Stone magazine.

“It was boring,” Truman insisted. Lee Radziwill and Peter Beard, who had accompanied Capote on the Stones tour, laughed at his explanation.

“Oh, I enjoyed it,” Truman continued. “I just didn’t want to write about it, because it didn’t interest me creatively, you know?”

Later, I learned that Truman had an incident with Keith Richards at a hotel somewhere in Middle America. According to Stones tour publicist Carol Klenfer, Keith did not “enjoy snobs,” and “basically hated what Capote stood for,” and was furious that Truman was on the tour. As the guitarist stated in his 2010 autobiography, Life, “I remember, back at the hotel, kicking Truman’s door. I’d splatter it with ketchup I’d picked up off a trolley. Come out, you old Queen. What are you doing round here? You want cold blood?” According to Klenfer—this part is not in the book—Keith then said, “I’m going to beat the shit out of you.” Needless to say, Truman did not come out of his room. He left the tour shortly afterward.

Of course, it was Andy who came to Truman’s rescue, as he would throughout the late 70s and early 80s, when Interview published a series of articles by Capote, which were later collected in Music for Chameleons. Capote had made a deal with Rolling Stone to publish his tour diaries, but he hadn’t written anything, and he was no longer on the tour. Andy assured the magazine’s publisher, Jann Wenner, that he would interview Truman about the 1972 tour so the magazine would have something to show for Capote’s expenses. So one summer morning, Andy, Truman, and I met at the Oak Room at the Plaza Hotel and wandered around Central Park while Andy interviewed Truman.

Jann Wenner was satisfied, and the interview was printed in the April 12, 1973, issue of Rolling Stone magazine as a cover story with the headline, “Sunday with Mr. C., An Audio-Documentary by Andy Warhol, STARRING TRUMAN CAPOTE”:

Andy Warhol: “Then the next question was, ‘The Plane Fuck.’”

Truman Capote: “They had this doctor on the plane who was a young doctor from San Francisco, about twenty-eight years old, rather good-looking… It developed that he had a super-Lolita complex. I mean thirteen-, fourteen-year-old kids. He would arrive at whatever city we would arrive at, and there would always be these hordes of kids outside and he would walk around, you know, like a little super-fuck and say, ‘You know I’m Mick Jagger’s personal physician. How would you like to see the show from backstage?’

“…The one I remember most was a girl who said she’d come to the Rolling Stones thing to get a story for her high school newspaper, and wasn’t this wonderful how she’d met Dr. Feelgood and got backstage…

“Anyway, she got on the plane, and she sure got a story, all right [laughs], because they fitted up the back of the plane for this. You know Robert Frank? He was on the tour. Robert Frank got out all of his lights, the plane was flying along and there was Dr. Feelgood screwing this girl in every conceivable position while Robert Frank was filming.”

Andy kept trying to help Truman, but it was probably already too late.

“He’s like a different person now,” Andy said of Truman in 1980, four years before the author’s death. “He’s very distant, not friendly.... It’s strange, he’s like one of those people from outer space—the body snatchers—because it’s the same person, but it’s not the same person.”

Vincent Fremont is the former vice president of Andy Warhol Enterprises and the former manager of Andy Warhol’s studio, The Factory. He is currently an adviser to ARTnews

Legs McNeil is the co-author of Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk and The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry