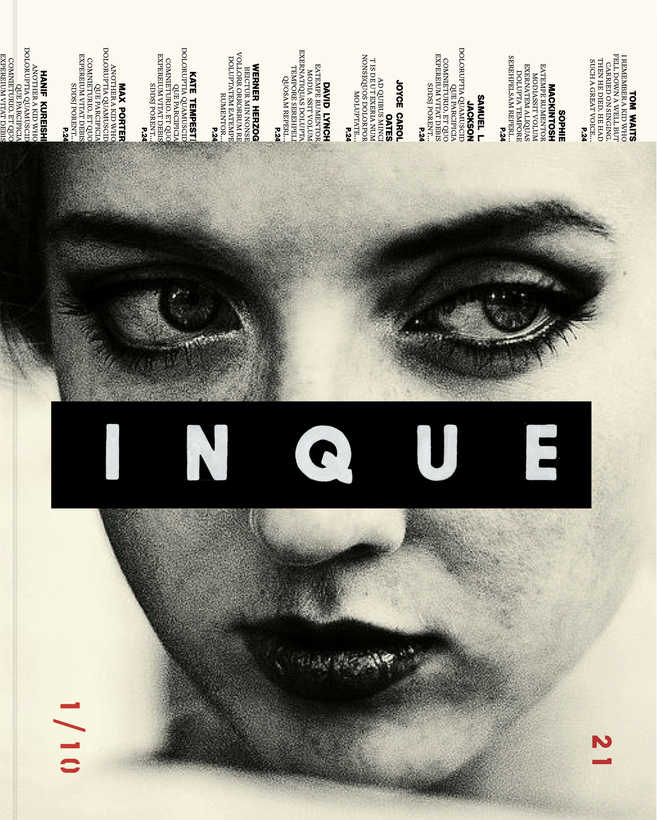

“We love making magazines and hate being told what to include in them,” goes the thinking behind Inque, a large-format, print-only literary publication that will publish yearly for 10 years starting next fall. Doing away with advertising and an online presence altogether, the magazine is relying on a Kickstarter campaign to fund its issues, putting the focus entirely on a beautifully-designed product and the creativity of the writers, photographers, and illustrators within its pages. Already on board: Joyce Carol Oates, Tom Waits, Samuel L. Jackson, Kate Tempest, David Byrne, and Ben Lerner. Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie has been tasked with discovering young African writers, while Jonathan Lethem will write a novel over the magazine’s 10-issue run. Adam Moss, formerly the editor of New York magazine, is the latest-announced recruit. Ash Carter spoke with Dan Crowe, the magazine’s founder.

Ash Carter: How did you get into magazines in the first place?

Dan Crowe: I sort of accidentally fell into magazine publishing in the late ’90s. I was the publisher and editor of a magazine called Butterfly, which famously got Zadie Smith, who was pretty much unknown then, to write “The A to Zed of Zadie Smith.” I just completely fell in love with how you can connect a group of people with a magazine.

I also figured out pretty early on that one of the important things in magazines is getting a great designer on board.

I went on after Butterfly to do a magazine called Zembla. The idea with Zembla was to make it a literary magazine, but sort of super accessible. I had the idea to get famous authors to interview dead authors—Rick Moody interviewed Jimmy Hendrix, Geoff Dyer interviewed Friedrich Nietzsche. It was just really, really fun and addictive reading. I liked the idea of making a literary magazine really fun. Zadie Smith reviewed her own books, actually, for that magazine.

Then, I realized that doing magazines in that way wasn’t really sustainable in terms of being able to pay for shelter and food and stuff. The whole advertising thing didn’t really work for literary magazines. Therefore, I launched Ports magazine with Matt Willey, who was, up until very recently, the art director of The New York Times magazine. I launched that almost exactly 10 years ago, and it’s still going.

Where did you get the idea to start Inque?

It’s really hard to build a magazine and make enough money to pay all the wages, and continue to push your own creative boundaries. Matt and I decided we were going to do another magazine that only had the things in it that we love, and got rid of all the things that we don’t like. One of the other things we don’t like is the ludicrous rising distribution costs for magazines, so we got rid of that. We got rid of the advertising.

Inque is a sort of hybrid magazine-book. We’re pricing it at a point whereby it’s accessible, but it’s still quite expensive: £45 ($60), if you get it on Kickstarter this month, or £55 ($70) on newsstands at about 10 locations globally, including in New York, L.A., Berlin, London, Milan, and Paris.

There will be no digital iteration of it at all; it’ll be sent direct to subscribers.

What will the first issue look like?

You’re going to have brand new writing from people like Tom Waits, and Kate Tempest, and Joyce Carol Oates, which won’t be writing that will appear anywhere else before or after. Jonathan Lethem is writing a novel throughout the 10 issues of Inque. That will be a new work of American fiction that you can only get inside of Inque. And there’s going to be a lot of hybrid collaborations. Ben Lerner is writing an original piece in collaboration with an artist. The British author Max Porter is doing a bizarre project with Pez.

Like the candy?

Yeah. He’s asking scientists and anthropologists and philosophers how they feel about certain Pez’s. We’ll photograph them all, and have them in this huge format magazine. It’s going to be nuts.

We just want to know what a magazine would look like when there’s no rush and you can commission your favorite artists, musicians, thinkers, philosophers to write whatever they want, and then see what happens. We’ll also have people like Wesley Morris of The New York Times, trying to perhaps articulate the year that we’ve just lived through.

How did you decide on the name? It’s a nod to tradition, but spelled in a nontraditional way.

In a playful way, we wanted to point very much to the physicality of this—that there isn’t going to be a digital iteration of it. If you want to buy it, you will have to get inky fingers.

What can you do with print that you can’t do in digital?

Similar to what’s happening here, or if we were in a park, sitting down, listening to each other, looking at each other, concentrating on each other, when you’re focusing on print you’ve got an exclusive, and very intense, connection with the author. The kind of writing by authors like Ben Lerner, or Joyce Carol Oates, or Max Porter, who have a very urgent and interesting agenda in terms of wanting to write intellectually, but also emotionally, is very powerful when it’s print. It’s less powerful when it’s digital. Now, I’m not saying it’s not possible. Reading Ben Lerner in The New Yorker online is great, but it’s definitely not as powerful as reading him in a book that you’re holding, when you’re sitting in a park—when you can concentrate on it, when you’re focused on it.

Another thing that print is able to do, and this might raise some eyebrows, is have hybrid collaborations. Print magazines are great environments to experiment in. Take the early Verve or Blast magazines of the 20th century—they were just incredible places for writers and artists to experiment. That has really fallen by the wayside.

Doing something that’s print, and print only, is going to ask people to slow down for a minute and consider it. Even having something like the Jonathan Lethem model only available in Inque over a 10-year period—I mean, you’re going to have to wait 10 years to finish this book. I think with digital, there’s a schizophrenia that is really hard to avoid. If something goes wrong, you can suddenly change it. One of the things that drives me nuts about digital is that I’ll be listening to one of my favorite albums, and then I’ll listen to it again two months later and they’ll have included a new track, or a track is suddenly longer. I’m like, “What are you talking about? This is an iconic record from the ’70s. You can’t just go back and change it.” It’s nuts. That’s what I like about print.

Port has a big digital iteration, and that’s really important. I think with Inque it’s really important to not have that.

I’m thinking, more and more, that Marshall McLuhan does not fully get his due as somebody whose ideas anticipated the world that we’re currently living in. I think that it’s not just digital technology, but social media that really changed the nature of publications. The relationship that you are proposing with your subscribers is one of mutual trust. Whereas, with the social model, there’s a constant pressure to change the content to suit what the hive mind wants that day.

The culture changes so rapidly, and it’s a bold move, I think, to commit to publishing something that’s commenting on the culture in this form so far in advance. Really, you’re committing not just to the contributions of these people, but also to the people themselves. You never know these days, who’s going to run afoul of the mob, for one reason or another. Basically, you’re going to be stuck with them for better, and worse. Is that something that you have thought about?

There’s a couple of people that we’re not promoting at the moment, in terms of being contributors to Inque, who I admire greatly. But I’m definitely against responding on a minute scale to things on a daily basis. I stand by all of the contributors that we’ve got up at the moment. I have a sort of diverse and interesting bunch of folks that are going to help us make something incredible.

Part of the toxicity issue is that whenever anyone does anything wrong, it seems, everyone gets terribly excited about it. People just tend to get destroyed online, and they’re not given the chance to apologize. But I’m really happy with the contributors we’ve got. I don’t mind at all projecting into the future and wondering what they might be writing about. I think it’s going to be wonderful.

How did that group come together?

Getting the contributors was my job. It’s something that I’ve just been doing, really, for 20 years or so, since my first literary mag. In fact, even before that. Growing up, I wrote to David Byrne. I was a really big Talking Heads fan, and I was just amazed to find him respond to me. The same happened with the artists Gilbert and George. I just couldn’t believe it—that you could actually reach out to people and they might write back. I guess, as an adult, that’s what I’m really doing. I’m just writing to people.

A lot of the writers involved—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jonathan Lethem, Joyce Carol Oates—need no introduction. Are there younger or emerging contributors that you’re excited about?

Actually, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s job is to bring in completely unknown African writers that she knows but we don’t, which is really exciting. Then there’s younger authors like Naoise Dolan, who’s just published in the U.K.

Inque isn’t going to be this beautiful book full of famous writers and really cool people. That’s not what it’s about. It’s certainly going to have some very established writers in it, and artists, but it’s about creative writing and how that interacts with art and design. There’s going to be some translation from foreign languages into English that hasn’t been done before, and a lot of new authors next to it. Obviously, I don’t even know who these authors are yet. They need to be new this time next year, and emerging. It’s a constant conversation with agents and editors, and just talking and listening to writers—who they’re excited about, who they want to read.

So there won’t even be a website?

We do need a website in order for people to pre-book. You can only go so far in terms of not being digital—it’d be like some guy in a forest selling issues of Inque, with ale, and cigars. There’s going to be a website, but the content isn’t going to be available online.

It’s just: if you like the idea of Inque, buy it.

Ash Carter is the Features Editor for AIR MAIL