What could be simpler than steam? Yet the global spa industry has found seemingly endless variations on hot-water vapor. There’s a Turkish hammam in Zurich and a Korean jjimjilbang in Sydney. Russian banyas can be found in New York, Paris, London, and Berlin. There’s even a banya in Buenos Aires that exiled Russians opened earlier this year. The extravagantly priced Aman hotel in New York has a banya “experience,” complete with a steam room and and birch-twig beatings, which costs $6,200 for three hours. (The upsides: you can bring one friend for no extra charge, and the hotel throws in a “personalized healthy lunch.”)

Steam rooms are no longer populated only by old men on The Sopranos. Younger generations are turning away from alcohol and bar culture and seeking out new places to socialize. There’s growing evidence, too, that heat therapies, especially sauna, can soothe joint pain among the elderly and even support cardiovascular health. A 2015 study by the University of Eastern Finland followed 2,000 male sauna users over 20 years and found that they had significantly lowered the risk of Alzheimer’s, strokes, and cardiac events.

I visit Porchester Spa, in West London, which costs all of $30. It’s not exactly high luxury. Each entrant must bring his own towel, and its depths are inhabited by strange and peculiar characters. Pass through the large wooden doors of the ticket office and you’ll discover an echoey hall with marble columns and checkered floors, illuminated by a plunge pool smack-dab in the center. Above is a brass statue of an Art Deco go-go dancer, her knee lifted to her elbow, a glowing orb in her right hand. The steam rooms and tepidarium, a relaxation area based on ancient Roman baths, are lined with cracked, aging, green-and-white tiles, some stained by the rusting pipes.

Steam rooms are no longer populated only by old men on The Sopranos. Younger generations are turning away from alcohol and bar culture and are seeking out new places to socialize.

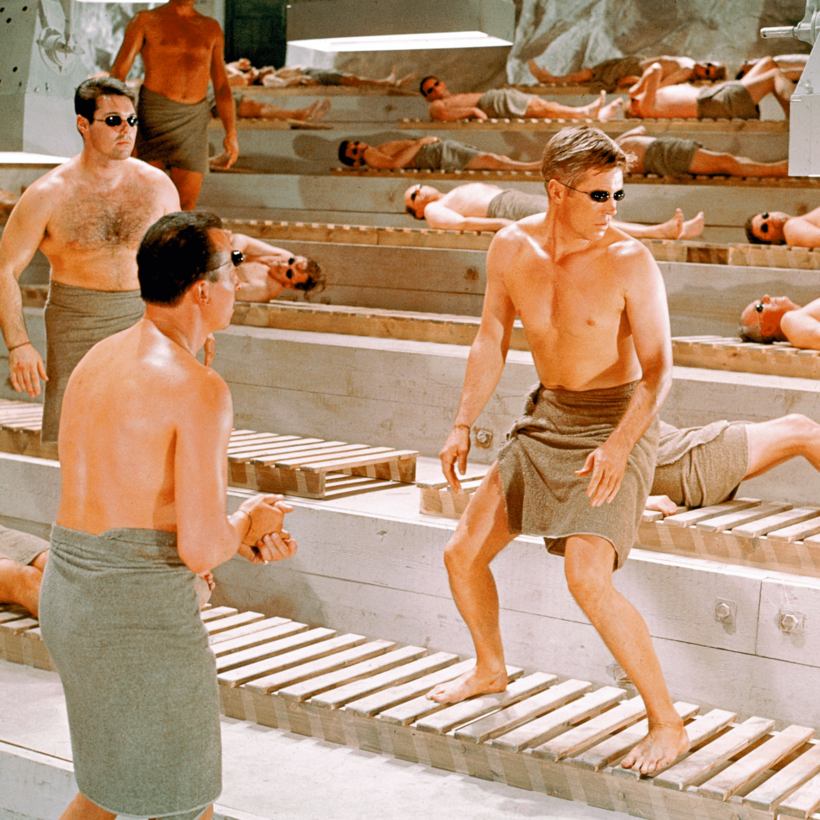

Men in robes, swim trunks, or nothing at all recline on wooden sun loungers, reading newspapers or snoozing. They are construction workers, retirees, police officers, lawyers, academics, and journalists. I’ve spotted the host of a BAFTA-award-winning television show in the plunge pool, and was told by one regular that Keir Starmer, Britain’s new prime minister, used to visit. Everyone here is both exposed and anonymous, sweating almost naked in front of strangers and yet often hidden within the steam.

The first time I visited Porchester, a regular called Mr. Ahmed handed out satsumas in the steam room. I once consoled a man whose girlfriend had just left him—he’d taken her to his flamenco lessons and she fell for another dancer. He was distraught twice over, mourning the woman and the pastime. There is a kind of intimacy in the building, a jokey camaraderie between bathers who often don’t know each other’s names.

Ruth Kaplan, a Canadian photographer who spent the 1990s documenting bathhouses around the world, told me men and women tend to behave very differently under the heat. She was especially struck by a segregated seaside spa in Copenhagen, which was entirely nude. “The men were all drinking and smoking…. Then they went into the sea, held hands in a circle, and sang a song,” she says. “Things were completely different on the women’s side—they were all exercising and talking about their health.”

Bathhouses have a bit of a reputation for seediness, but there is little evidence of illicit practices at Porchester beyond a commitment to exhibitionism. In the main hall, I’ve observed a naked man pour boiling water from a thermos into a pot of instant noodles. The regulars strip down and take turns lathering the branches with soap, and then use them to beat each other, covering themselves in the suds. It is, they told me, a technique they learned from Jewish immigrants. Anyone can join in, provided they supply a bar of Dove soap—for some ancient reason, it has to be Dove—and $7 for the straw brushes.

Porchester attracts a few oddballs. A gangly older gentleman was once escorted from the premises, insisting that he would sue after a staff member accused him of taking furtive pictures of fellow bathers.

The hammam-curious might want to start with a mixed-gender day, when bathing suits are required. The crowd is generally younger, and it includes more couples and groups of friends. And what could be more therapeutic than sharing your troubles—and a satsuma—with a sweating stranger?

Gus Carter is the deputy features editor at The Spectator