There was pandemonium inside the Waldorf Astoria’s grand ballroom on January 31, 1978, the day Andy Warhol helped introduce the Polaroid 20x24 camera to the world.

More than 700 journalists, Wall Street analysts, and assorted gawkers had crowded excitedly into the room to watch the disciples of Polaroid founder and prolific inventor Edwin H. Land—“Dr. Land,” as this college dropout was universally known—unveil his latest technological miracle: an 800-pound, wood-and-metal behemoth, part camera, part darkroom, part instant printer, that could produce life-size, high-resolution color portraits, 20 inches wide by 24 inches high, in a few blinks of an eye.

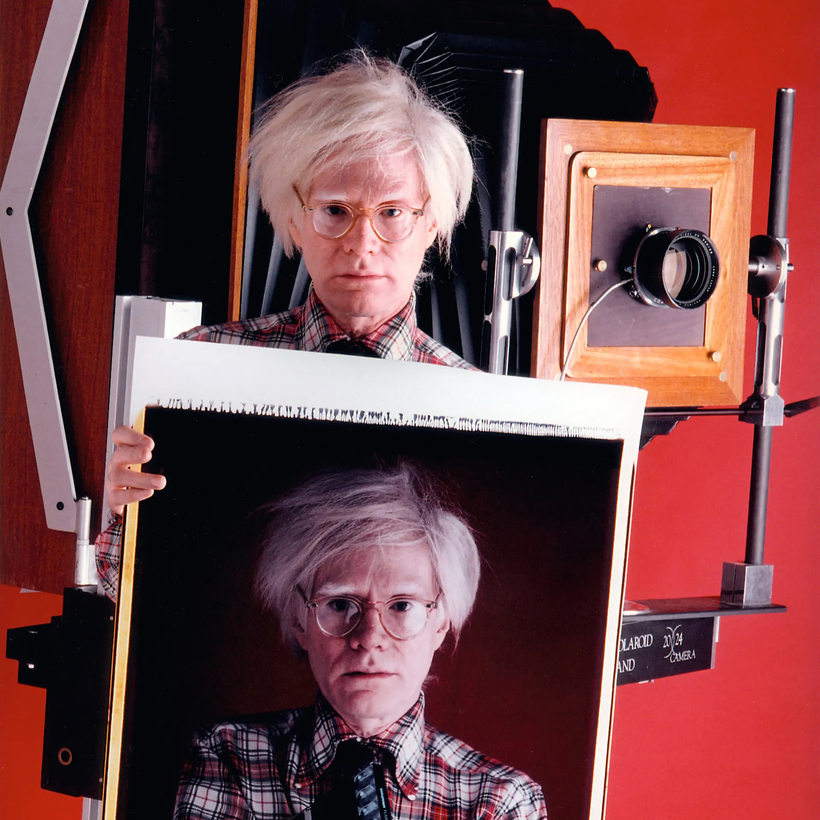

“Selected guests were ushered to the stage to pose before the giant camera, among them a white-haired, bespectacled artist [Warhol] who stood out in the crowd of conservative businessmen and women,” former Polaroid executive Barbara Hitchcock wrote decades later. “The shutter clicked, the strobes flashed and the negative was exposed. Exiting from the camera’s back, the PolaColor film was hung on an easel. Sixty seconds later, the negative portion was peeled away and a brilliant color portrait was revealed,” an image that was so stunning and minutely detailed—the photographic equivalent of cloning—that it “pitilessly display[ed] his mottled skin.... Warhol posed with his ‘replica’ for the crowd of photographers and television crews that pressed toward him.”

Photographic artist JoAnn Verburg, who was in the audience with her friend Peter MacGill, later the co-founder of New York’s Pace/MacGill Gallery, remembers the circus-like spectacle as “a debutante ball for the camera.”

The 20x24 was the physical embodiment of Dr. Land’s ambition to always be at the intersection of art and technology. At his direction, Polaroid’s design teams, comprising dozens of scientists, engineers, woodworkers, and metalworkers, built five production models in a slimmed-down, 225-pound version. With a corporate culture that disdained bean counting—“The bottom line,” Dr. Land famously declared, “is in heaven”—Polaroid then established its Artist Support Program, in which dozens of celebrated photographers and painters were invited to experiment, free of charge, with the new large-format technology.

Dubbed the Giant Polaroid, the camera eventually became a favorite medium of expression for such notable creators as Robert Rauschenberg, William Wegman, Jim Dine, Chuck Close, Elsa Dorfman, Mary Ellen Mark, David Levinthal, Ellen Carey, Peter Beard, Natalie White, and naturally Warhol, an early adopter of all things Polaroid.

Many of these artists—including Warhol, Close, and Wegman—were featured among the 300-odd Polaroids in a recent major exhibition at the Fundación Barrié in A Coruña, Spain. Meanwhile, the Fox Talbot Museum at Lacock Abbey—named for one of the founders of photography, William Henry Fox Talbot—is currently exhibiting “Light-Struck,” a selection of 20x24s by Ellen Carey, inspired by Fox Talbot’s genius. And opening July 22, at the Ethan Cohen Gallery at the KuBe Art Center in Beacon, New York, is “The Last Shot,” a collection of Natalie White’s 20x24 portraits of artists, curators, politicians, and other community leaders.

Wegman, who made frequent use of the camera from 1979 until 2007, often to stage strikingly oddball scenes with his Weimaraner dogs, was at first skeptical that the Giant Polaroid would fit his stringent aesthetic sensibility. “I wanted my photographs to look like they were in a magazine or in a book, rather than on a wall,” Wegman, 78, told me. “I begrudgingly went [to the 20x24 studio in Cambridge] and I immediately became fascinated with it. It really changed my whole way of thinking about photography.” During Wegman’s first 20x24 photo shoot with his dog Man Ray, whom he posed in chiaroscuro against a black drop cloth, he flouted his no-color rule by painting one of Man Ray’s toenails with bright Revlon Red nail polish. “It really broke apart my rigid manifesto, and it opened me up to an amazing amount of directions, with or without the dogs,” he said.

The much younger artist Natalie White has continued to use the 20x24 camera to make double-exposed self-portraits since her breakout 2013 exhibition at New York’s Rox Arts Gallery, “Who Shot Natalie White?” “There’s this magic,” White says, “to double-exposing a Giant Polaroid where you just give up all control to the camera.”

“I don’t want that control.... Having too much control over what the final image looks like is not a good thing, because you overthink yourself, you make it too perfect,” she says. “Life isn’t perfect, and art shouldn’t be perfect either.”

David Levinthal—whose 20x24 art features toy soldiers, cowboys, Barbie dolls, and other children’s playthings to create a haunting, occasionally disturbing, world of American mythos—began using the camera prolifically in the early 1980s, shooting as many as 70 images in a single session. “The 20x24 has such a significant and unique place in photography, as does Polaroid in general. That’s always going to be there,” Levinthal says.

Not every artist was sold, however. David Hockney declined an invitation to work regularly with the 20x24 after experiencing the technical traumas of an even larger experimental Polaroid camera, the room-sized 40x80. “Big cameras, big problems,” he said by way of begging off (although Hockney did end up making at least one 20x24 print, a portrait of his mother, Laura).

“The bottom line,” Dr. Land famously declared, “is in heaven.”

It turned out that the 20x24’s “debutante ball,” at the Waldorf Astoria in January 1978, was the Polaroid Corporation’s high-water mark as a thriving, publicly traded company with a global workforce of 21,000, multi-billion-dollar revenues, and the visionary leadership of a creative, scientific, and (it must be said) public-relations genius.

Just four years later, Polaroid’s fortunes disastrously began to reverse. Dr. Land left as chairman after ordering the ill-advised investment of hundreds of millions of dollars into the development and marketing of “Polavision,” an instant—but soundless—home-movie system that could produce less than three minutes of film at a clip. Unfortunately, the product was scheduled to be introduced just as user-friendly videotape cameras were entering the consumer marketplace.

At a 1977 meeting at the company’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, headquarters on Technology Square, Dr. Land proudly showed off his latest marvel to his dear friend Akio Morita, the co-founder and chairman of Sony. “I was there to demonstrate … so I demonstrated it, and there was a long silence in Land’s office,” longtime Polaroid communications executive Eelco Wolf recalled. “Land was actually a very shy man, by the way, but he looked at Morita and he said, ‘What do you think?’”

Morita said, “It’s a fantastic scientific innovation, but it’s past its time.” Land didn’t say anything, Wolf recalled.

“It was too late to bail out—as if Land would even consider doing so—and the marketers did their best,” Christopher Bonanos wrote in Instant, his entertaining history of the company, noting that Land’s friend and adviser Ansel Adams, Warhol, and even John Lennon had tried using the contraption to make short silent movies. Bonanos estimates that Polaroid sold about 60,000 systems—a fraction of the 200,000 they had projected. Polavision, which cost some $500 million to develop, was discontinued in 1979.

Three years later, Dr. Land, who holds more patents—535—than any American inventor with the exception of Thomas Alva Edison and one of Edison’s associates, was either coerced or persuaded to step down by his handpicked leadership team and corporate board. He ultimately distanced himself from the company he created in his own image, not even bothering to attend Polaroid’s 50th-anniversary gala in 1987, and died in 1991, at age 81, having instructed an assistant to shred his personal papers.

It was a shocking dénouement. Land, who grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, the son of a Russian-Jewish scrap-metal dealer, had withdrawn from Harvard in 1927, at age 18, to move to New York City and pursue his own innovations in the polarization and filtration of light, climbing onto a window ledge to sneak late at night into a locked Columbia University lab in order to conduct his experiments. He launched his company in 1937, never getting a college degree, and marketed the first instant Polaroid camera in 1948; a decade later, Harvard awarded him an honorary doctorate. By 1978, Polaroid was an iconic brand name alongside Coca-Cola and Mickey Mouse.

Among Dr. Land’s many admirers was Apple founder Steve Jobs, who made the pilgrimage to Cambridge to commune with Polaroid’s creator; Barbara Hitchcock recalls that one of their sessions, scheduled for a brisk hour, lasted more than four. Dr. Land is frequently cited as the Steve Jobs of his era. However, Polaroid’s former communications chief for the United States, Sam Yanes, argues that it should be “the other way around.” Yanes recalled that when, in 1985, “Steve Jobs did a Playboy interview … and he compared himself to Land, Land asked me to get on the phone and tell him to cut it out.”

“I think I just left a voice message or talked to Jobs’s P.R. person,” Yanes recalled. “The issue for Dr. Land was that Jobs says that he was forced out of Apple in the same way that Land was forced out of Polaroid, which bothered Land no end, because a) it wasn’t true and b) he didn’t want to be compared with Jobs.”

That was understandable: although Jobs was a high-concept design virtuoso and brilliant pitchman, Dr. Land was a builder and scientist who liked to roll up his sleeves and plunge into the gritty details of physics, engineering, and chemistry.

Nor would Dr. Land have been thrilled with Jobs’s claim in the Playboy interview that Polaroid was no longer “one of the five most exciting companies in America,” a decline that Jobs felt Xerox was also experiencing. “Companies, as they grow to become multibillion-dollar entities, somehow lose their vision,” Jobs had said. “The creative people, who are the ones who care passionately, have to persuade five layers of management to do what they know is the right thing to do. ”

Jobs’s comments proved prophetic. Polaroid filed for the first of its two bankruptcies in 2001. The company Dr. Land had led for 45 years then changed hands several times, at progressively lower valuations, before succumbing to a second and final bankruptcy in late 2008, a few years before that of its chief competitor, the once mighty Eastman Kodak.

The Polaroid brand name lives on, however, in cameras, instant film, and other products, largely due to a group of European true believers working to raise it from the dead. They include Dutch engineer André Bosman, the former managing director of the Polaroid’s Netherlands film factory, Austrian businessman Florian Kaps, and Polish investor Wiaczesław “Slava” Smołokowski, who since 2017 has been the majority owner of the new Polaroid company run by his son Oskar.

A Handful of Elders

Practically alone among Dr. Land’s magical machines, the 20x24 camera lives on. Barely.

The fact that it continues to exist at all is due to a photographer, artist, and documentary filmmaker named John Reuter. Fresh out of graduate school in 1978 with an M.F.A., Reuter (pronounced “rooter”) was hired as a Polaroid research photographer but initially resisted an offer to also run the company’s newly established 20x24 studio in Cambridge. He preferred Polaroid’s SX-70. Pocket-sized, massively popular, and beautifully designed, the collapsible steel-and-leather SX-70 racked up more than a billion dollars in sales. (This writer was among the millions of Americans who owned one.)

By 1980, Reuter was having a change of heart and finally took on the job of working with the Giant Polaroid, aiding the various creators who’d been invited to use it by JoAnn Verburg, who ran the company’s Visiting Artist Program. “My role was to be like a D.O.P. [director of photography] for others,” Reuter says.

“It’s really more like a Panavision film camera in that it needs a crew,” Reuter adds. “It needs a lot of staging. It can be very fussy. It’s mechanical. It’s subject to all kinds of physical challenges—how you pull [the sheets and negatives from the camera after exposure], what the humidity is in the room, how warm it is. People who try to do it on their own end up getting frustrated and give up.”

The camera has taken Reuter, who’s working on a documentary about the Giant Polaroid, on adventures all over the world, including a January 2020 trip to China to meet with new clients three days before the coronavirus locked that country down. Reuter also assisted Chuck Close, who died in 2021, in shooting 20x24 portraits of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama during their presidencies. Over the course of 2013, Reuter and Close made 20x24 portraits for the 2014 Hollywood Issue of Vanity Fair, including one of its then editor, Graydon Carter, now a Co-Editor of Air Mail.

“John’s getting older, and without John, nothing will happen,” says Eelco Wolf, who relocated the 20x24 Studio in 1986 from Cambridge to New York’s SoHo neighborhood, where it would have a better chance at breaking even and be more accessible to artists willing to pay for studio time (these days, a prohibitive rental fee of around $2,000 a day for studio time with the camera, plus $200 for each printed image).

At one point in the early 1980s, Polaroid quietly sent a 20x24 camera to Saudi Arabia, along with a full complement of executives and technicians, in order to make portraits of the Saudi royal family. Reuter didn’t go. “They were at the beck and call of the royal family and treated like servants,” he heard from a colleague, who was “particularly annoyed because there was no booze for the whole trip.”

More promising as a moneymaker in the 1990s was “this side racket of bar mitzvahs,” says Reuter, who recalled hauling a 20x24 camera to nearly a dozen such soirées at New York’s finest hotels, not only for various 13-year-old members of the Tisch family but also for their close circle of friends, including the financier Leon Black.

“I gave them such a high estimate [$8,000 a night], I thought, surely they wouldn’t do it, but they did it,” Reuter says. “Money was no object. We would shoot, like, 160 portraits of party guests. The funniest thing was you would have all these elites standing on line for 45 minutes to an hour to get a Polaroid done, and these people never stand on line. And sometimes the party planner would make us break, because they had to be seated for dinner, and people would refuse to move. I’m not moving till I get my picture!”

“I don’t know if I could do 160 pictures in a night again,” says Reuter, who had a knee replacement in December 2021 and underwent radiation treatments for highly curable stage-two prostate cancer last year. His work has taken a physical toll that includes carpal-tunnel syndrome and multiple surgeries. He also went under the knife for spontaneous nosebleeds, the result of decades of exposure in claustrophobic environments to irritant developer chemicals. Reuter’s former partner in the production lab, who recently retired, is 82. “I do have a younger former Polaroid guy coming in. He’s 65. I’m 70. So what we’re left with is a handful of elders.”

In 2007 Polaroid stopped making cameras entirely, and in 2008, the company stopped making instant film, previously Polaroid’s profit center. The 20x24 camera, which Dr. Land conceived in the mid-1970s as a way to wow the folks in the cheap seats at the annual shareholders’ meeting, was always a corporate reputation-enhancer, never a viable commercial product.

Minnesota businessman Tom Petters, whose holding company had bought the stripped-down Polaroid Corp. in 2005, had zero interest in the 20x24 camera, much less the “photographic arts, or imaging technology,” as Christopher Bonanos wrote in Instant. “What he wanted was the real estate, the art collection, the trademark, and the right to convert all those things into cash.”

When, in 1985, “Steve Jobs gave a Playboy interview and compared himself to Land, Land asked me to get on the phone and tell him to cut it out.”

“He was—pardon me—an asshole,” a Polaroid finance executive told Bonanos, by way of describing a bizarre team-building exercise. “When he first came to the headquarters, he called a meeting of senior Polaroid management in the cafeteria, and he had people climb up on tables and made each one sing a song. Then he’d give them ten dollars.”

In September 2008, Petters was arrested by the F.B.I. for financial crimes and is currently serving a 50-year prison sentence at Leavenworth for orchestrating a $3.7 billion Ponzi scheme that he’d hatched years before the Polaroid acquisition. “He looked good in orange,” says Barbara Hitchcock, who during her 29-year career at Polaroid diligently contributed to the company’s employee stock-ownership plan, only to see her retirement nest egg plunge from around $30 a share to nine cents a share.

Equally distressing, a bankruptcy court in Minnesota ordered that huge swaths of the Polaroid Collection—the Hitchcock-curated collection of around 1,200 photographs including many 20x24 prints donated by prominent artists in exchange for their use of the camera—be sold at auction to compensate creditors.

“It’s an amazing body of work,” Chuck Close said at the time, after attempting to rally fellow artists to the quixotic cause of keeping the collection intact. “There’s really nothing like it in the history of photography.... To sell it is criminal.” (Also lucrative: the Sotheby’s auction in June 2010 fetched more than $12 million.)

After the company went belly-up, Reuter spun off the 20x24 Project as an independent enterprise and acquired, with the financial help of philanthropist Daniel Stern, the chairman of Film at Lincoln Center, around 500 cases of remaining 20x24 film that had been sitting in a Polaroid warehouse, and which is now years past its expiration date.

With supplies of the company’s reagent—the delicately complex cocktail of nearly 20 chemicals that activates the instant-developing process—dwindling rapidly, Reuter collaborated with a retired Polaroid chemist to duplicate and even tweak the proprietary formula to make new reagent pods compatible with the gears and rollers that process the negatives and sheets inside the camera.

“Material-wise, there’s enough for another five years, I think,” Reuter predicted. Eelco Wolf told me his former colleague’s estimate is probably “too generous.”

Pure Magic

Reuter maintains two of the original five Polaroid-made 20x24 production models. One is stationed in western Massachusetts, where Reuter lives, and the other on Manhattan’s West Side at Film at Lincoln Center, thanks to Stern. Stern is helping to bankroll the mission largely for sentimental reasons—his close friendship with Giant Polaroid artist Elsa Dorfman, the subject of a 2016 documentary by Errol Morris.

The three other original 20x24s, all made between 1977 and 1978, are stationed, variously, at the Harvard Museum of Scientific Instruments (an inactive model); an arts complex in Berlin; and at the site of the former Polaroid film production plant in Enschede, Netherlands (also inactive). A sixth, prototype camera is in the collection of M.I.T.

In addition, a tiny San Francisco outfit, Mammoth Camera Company, the brainchild of Reuter’s former assistant Tracy Storer, has painstakingly hand-made three 20x24 cameras—each taking more than a year to produce and costing in the $150,000 range, according to Reuter—that closely hew to the original Polaroid design. Storer, says Reuter, is currently completing his fourth camera for a buyer in Shanghai.

To get a look at an actual 20x24 camera, I traveled from my home in southern France to Berlin, where Markus Mahla, an ebullient entrepreneur, restaurateur, and former Polaroid marketing executive, keeps one of the original Giant Polaroids along with a Mammoth Camera facsimile at the massive Soviet-built Funkhaus Berlin compound on the River Spree.

Erected from cannibalized Nazi architecture after World War II, the place was the headquarters of East German radio propaganda during the Cold War; the mammoth Bauhaus structures still look a tad Orwellian. But these days Funkhaus Berlin is better known as an early champion of techno music and a pop-cultural mecca featuring a concert hall with wonderful acoustics as well as state-of-the-art film, music, and video facilities.

“The whole Polaroid process is maybe still the most complex chemical process on the planet Earth,” says the 56-year-old Mahla. “What Edwin Land has invented is still a wonder. The film is developing with that chemistry—all these elements, all the dyes, all the developers that go onto the two surfaces between negative and positive—and then this development process stops at the right moment. That’s pure magic.” You have to be careful because the acids in the chemical pods are very toxic, he added. “It can burn your skin.”

Mahla suggests that he take my 20x24 portrait using the Mammoth Camera facsimile in his second-floor studio, because the original 1978-vintage camera was being operated that day by an artist in Amsterdam. He adds a warning: “I have people crying in front of me,” he says, when their picture comes out.

“You’re not going to get that from me,” I say.

“The camera can be scary—when you haven’t stood in front of such a camera before,” Mahla goes on. You take it to film festivals and meet “those big, big names, and they get very respectful and different in front of that camera, even though they stand in front of a camera all day.”

Mahla recalls the emotional responses of several members of the public when he made their portraits a few years ago during a Berlin photography exhibition.

“You do the picture, and the picture comes out, but still the negative is on it—it’s black,” he says. “So you stare at that black backside, and you wait and you wait. And that curve of being excited is going higher and higher and higher. And then you suddenly say, ‘O.K., let’s peel it off.’ Sometimes I ask the customer to peel it off, and they have shaking hands and they can’t do it. And the moment you peel it off, you see yourself life-size. I have very rarely seen people not being excited in any way.”

In his studio, Mahla neatly tapes two chemical pods together and loads them into a socket in the wood-encased rear compartment where, after an exposure of around a quarter-second, the rollers will explode their contents and, if all goes well, spread the emulsion evenly between the negative roll and the positive sheet.

Mahla positions me standing in front of the gigantic machine, which he slides back and forth to adjust focus, draping his head with a black cloth while gauging my upside-down image in his viewfinder. I hold a cell-phone flashlight in each hand aimed at my face so Mahla can play with the lighting. The experience is something like getting a dental X-ray—less physical discomfort, of course, but far more intimidating.

Finally, Mahla is ready to take the picture. I concentrate on not blinking or smiling, and reflexively lift my head in hopes of avoiding turkey neck as he pushes the button and the flash goes off. Mahla pushes another button to activate the roller and coaxes down the sheet, slicing across the top with an X-Acto knife. He lays the sheet on the floor and after letting it marinate for a minute, carefully peels off the negative.

The result, which will need overnight to dry, is a one-of-a-kind, unreproducible analog image—in a different universe from digital, and with a texture more like a painting than a photograph. I don’t cry, but I have to admit, it looks pretty cool.

Lloyd Grove is a France-based journalist. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, and the Daily Beast, among other publications