October 16, 2022, was a seemingly typical night at Beckett’s, the short-lived and much-lamented downtown literary salon. The crowd at the rambling town house in New York’s West Village was the usual mix of writers, artists, Off Off Off Broadway actors, techies, and “young bourgeois professionals,” recalled Mike Crumplar, who chronicles the scene in his newsletter, the Crumpstack.

The host of the event, Beckett Rosset, the 53-year-old writer, former heroin addict, and son of the late Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset, was surrounded by his usual retinue of twentysomething women. “There was a lot of cigarette smoke, people doing lines of coke, and building violations,” according to the critic and Air Mail contributor David Yaffe. “It was a totally decadent, bacchanalian ambience.”

But tonight, the buzz at Beckett’s was cut with something rich and strange. No, it wasn’t an S&M orgy, or some stomach-churning piece of performance art. That would have been par for the course at a modish downtown gathering. Instead, this group of assorted bohemians were lining up to listen to a debate on a subject even more timeworn than the building they were gathered in: the Shakespeare authorship question.

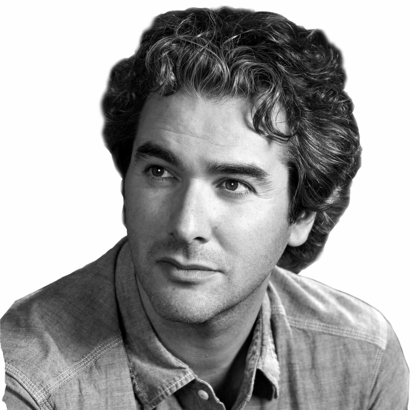

On one side, arguing the mainstream view that William Shakespeare was the author of Hamlet, was Matthew Gasda, 34, from Brooklyn. A guerrilla playwright best known for his scene-defining play, Dimes Square, Gasda came to fame during the pandemic for thumbing his nose at coronavirus regulations and, in true “show must go on” fashion, putting on performances in people’s living rooms. With a dramatist’s devotion to the Bard, and a former champion college debater’s rhetorical skills, he was not to be underestimated.

Against him, arguing the “Oxfordian” position (about which more in a moment), stood Curtis Yarvin, 49, a software engineer turned political gadfly out of Berkeley, California. Yarvin has won a sizable following in recent years for his dizzyingly garrulous blog posts—first under the nom de guerre Mencius Moldbug, more recently on his Substack, Gray Mirror—filled with contempt for the liberal consensus. His writings, and his friendship with the libertarian tech billionaire Peter Thiel, have made Yarvin a leading figure of the New Right—and a bogeyman of the online left. Able to talk the hind legs off a donkey, he was ready for a scrap.

This group of assorted bohemians were lining up to listen to a debate on a subject even more timeworn than the building they were gathered in: the Shakespeare authorship question.

Proponents of the Shakespeare authorship question believe that William Shakespeare did not write the timeless tragedies and comedies for which he is renowned. So who did? At one time or another it was thought to be the philosopher Francis Bacon. Others have suggested it was Shakespeare’s contemporary the playwright Christopher Marlowe. But for the last 100 years or so, the prevailing view among Shakespeare skeptics—and the one being propounded by Yarvin at Beckett’s that evening—was that the plays were the work of Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I, a grand patron of the arts, and an all-round Renaissance man.

Believers in this theory, known as Oxfordians, don’t deny that William Shakespeare existed. However, they hold that it would have been impossible for the son of an illiterate glove-maker, living in a provincial English town, with a grammar-school education at best, to create works of such distinction. They point to the paucity of documentary evidence about him; to the fact that there are essentially no manuscripts written in his hand; and to the absence of any references to plays, poetry, or even books in his will.

The aristocratic de Vere, on the other hand, was one of the most educated men in Europe, a court insider, and a poet and playwright. Shakespeare, say the Oxfordians, was simply a pseudonym the earl used to publish his sometimes politically daring plays, the name being a pun on his crest: a lion shaking a spear.

(Up until his insertion into this debate in the early 1920s, de Vere was best known for having broken wind in front of Queen Elizabeth I. Ashamed at his faux pas, he exiled himself to Europe hoping time would erase the memory of his transgression. On his return to the English court, a full seven years later, the Queen welcomed him with the words, “My Lord, I had forgot the fart.”)

The idea that Shakespeare was just a pseudonym has had a number of well-known advocates. Mark Twain thought Shakespeare’s threadbare biography was like “a Brontosaur: nine bones and six hundred barrels of plaster of Paris.” Sigmund Freud was convinced that “the man of Stratford seems to have nothing at all to justify his claim, whereas [de Vere] has almost everything.”

In more recent times, actors such as Derek Jacobi, Mark Rylance, and Keanu Reeves all seem to have been driven to the Oxfordian side of the argument after performing in the plays. Anonymous, a 2011 film with a 46 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, presents the thesis as fact. Even Hilary Clinton has doubted what is known as the Stratfordian consensus, proving that being the subject of a conspiracy theory does not preclude you from believing in one.

“Take the de Vere Pill”

It is perhaps unsurprising to learn that the latest revival of this debate came amid the febrile early months of the pandemic, as rumors swirled around the Internet that the coronavirus was caused by cell-phone towers and that vaccines had tracking microchips in them.

“It was 2020, and I had a lot of time on my hands and was feeling pretty down and out,” recalls Phoebe Nir, a 30-year-old playwright and filmmaker. After watching a YouTube video made by dyed-in-the-wool Oxfordian Hank Whittemore, an 81-year-old actor turned author, Nir said she felt “jolted by electricity.”

Nir, who had studied Shakespeare at college, found herself scurrying to read everything she could about de Vere. Soon she was making TikTok videos laying out the many claims—at once simple and convoluted—for the Oxfordian thesis. Her wide frame of reference—for instance, comparing de Vere to Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator, “Satoshi Nakamoto”—quickly won her a following. The tiny world of de Vere scholarship had never seen anything like it.

In her TikToks, Nir speaks with a machine-gun patter directly at the camera while her disembodied head floats over Elizabethan imagery and Shakespearean quotations. One of her favorite techniques is drawing out a hidden subtext in a play, such as in her 56-second-long foray into the character of Bottom, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, who Nir suggests was based on the French duke of Alençon, one of Queen Elizabeth’s suitors—proof, she asserts, that de Vere wrote the play. “Once you understand that Lord Edward de Vere … was commenting around the controversy of Queen Elizabeth’s marriage, you start to get what the real joke was,” she tells her followers.

Last August at Alger House in New York’s West Village, Nir hosted the De Vere Ball, which she calls “the Big Bang of Oxfordianism.” There was a zine titled “Take the De Vere Pill,” and a lutist played Elizabethan music as around 100 people—Whittemore among them—mingled and talked Shakespeare. A follow-up was planned: the debate at Beckett’s.

In her TikToks, Nir speaks with a machine-gun patter directly at the camera while her disembodied head floats over Elizabethan imagery and Shakespearean quotations.

That October night, as pictures of Shakespeare and de Vere were projected on the walls, Gasda launched forth to attack the Oxfordians, and Yarvin parried.

“It’s obviously, factually, a very, very corrupt theory,” Gasda tells me of his opponent’s position. “[De Vere’s] timeline doesn’t even come close to matching Shakespeare’s. It takes a massive stretch of the imagination to even make it work.” Gasda notes that “there are many, many allusions to the Gunpowder Plot in Macbeth,” which, he adds, is problematic considering it took place in 1605, the year after de Vere’s death.

Yarvin remains equally assured. “Being an Oxfordian is just the ineluctable consequence of taking the Elizabethan period seriously,” he says. “There’s a lot of things that people use against the Oxfordian hypothesis that remind me of the Johnnie Cochran school of legal reasoning. When people say The Tempest must have been written after 1604 because it refers to this specific shipwreck, I’m like, you know a lot of shipwrecks were going on at the time, right?”

No vote was taken at the end, but according to Crumplar, Gasda seemed to have persuaded more people in the audience, while Yarvin got more laughs. Both participants described the night as “fun,” but the hidden subtext of the debate was brought to the fore by Gasda in an article published in March on the Web site Compact.

“Oxfordianism has taken on a meaning that transcends its roots in fringe scholarship,” he wrote. “De Vere has been reborn as a rallying point for, and signifier of, a certain kind of unorthodox conservatism.” Gasda’s belief was that the Shakespeare debate was being used as a Trojan horse by Yarvin and his followers to challenge the liberal political order. Or, as the writer John Ganz put it on Twitter recently, “Stating that [de Vere] was Shakespeare is a fascist dogwhistle.”

Gasda’s claim is something Yarvin freely admits to. For him the Shakespeare debate offered a gateway to get people doubting much bigger social constructs—like democracy. “Once you find these holes in the fabric of what you thought was reality,” says Yarvin, “you don’t take anything for granted.”

It seemed only right at this point to turn to Sir Jonathan Bate, one of the world’s leading Shakespearean scholars. His most recent book, Mad About Shakespeare, a personal “bibliomemoir” about his life with the Bard, includes an entire chapter on the authorship question. In it, he recalls a conversation in 2007 with then Prince Charles during the interval of a performance of Henry V. Charles complained that his family always fought at Christmas because his father, Prince Philip, didn’t believe that Shakespeare wrote the plays. Bate provided him with a page of facts with which to rebut the cantankerous Philip.

Bate himself was an Oxfordian as a young man, although he has since recanted. Oxfordianism was, he says, a “dalliance with heresy,” something to make you “a bit distinctive, a bit clever, if you’re a bit of a show-offy teenager, which I guess I was.” He says he stuck with the theory “for as long as I could, even trying to convince my college tutor.” But at some point he took a hard look at the various claims and realized they didn’t add up. “The real question,” Bate writes, “should be: how could anyone but a glover’s son have put in his plays so much accurate technical detail about leather manufacture and the process of glove-making?”

“My view of Shakespeare is that he is the absolute exemplar of meritocracy and social mobility,” Bate says. “For anybody with a liberal disposition, that’s an inspiring story.” The idea that a normal, middle-class tradesman could write such plays is, in Bate’s view, a direct challenge to the New Right’s idea that liberalism is a failure.

The fabric of reality is exactly what Bate is concerned about. “If you start denying the evidence that we do have about the identity of Shakespeare, where do you stop?” Bate says. He mentions Joseph Sobran, a noted Oxfordian who became a Holocaust denier. “I think at a time when we have all this cultural turmoil and political division, just keeping a grasp on the importance of historical truths really does matter.”

Thinking back to that night at Beckett’s, Yaffe has a more sanguine take. “Frankly,” he says, “I was just glad to see young people caring about Shakespeare.”

George Pendle is an Editor at Large at AIR MAIL. His book Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons became a television series for CBS All Access. He is also the author of Death: A Life and Happy Failure, among other books