By 1963, Richard Burton’s tempestuous affair with Elizabeth Taylor had made him the subject of scandal and concern both to the tabloid hoi polloi and to the theater’s talentocracy. “Make up your mind,” Sir Laurence Olivier wired him. “Do you want to be a great actor or a household word?” Burton cabled back: “Both.”

The maelstrom of conflicting titanic ambitions came together the following year on Broadway in Burton’s Hamlet, directed by the most revered of England’s Shakespeareans, Sir John Gielgud, who had played the part more than 500 times in six productions between 1930 and 1946. The production was a portentous theatrical occasion, made all the more sensational when Burton chose that moment to become Taylor’s husband No. 5.

Gielgud’s concept for Broadway was to strip away the period folderol and to stage Hamlet as a rehearsal in modern dress. Jack Thorne’s slick, shrewd The Motive and the Cue (at the National Theatre, elegantly directed by Sam Mendes) uses the Gielgud-Burton production of Hamlet and repeats the conceit of rehearsal. But this time reconfigures it to dramatize the jousting of the two theatrical dynamos, who are on opposite sides of the seismic cultural shift in British public taste wrought by the welfare state.

A new kind of postwar working-class hero was being called onto the English stage and screen, with new kinds of actors, new values, new energies. Caught in the slipstream of these ferocious changing social crosscurrents of the late 1950s, West End grandees such as Noël Coward, Terence Rattigan, and Gielgud—who had dominated the boulevard for two decades—found themselves suddenly denigrated and deposed. “I am yesterday’s stale toast,” Gielgud says in the play. And indeed he was.

In hitching his vast experience to Burton’s rising star, Gielgud was trying to stay relevant. Conversely, in his bid to establish himself as the greatest Shakespearean actor of his generation, Burton wanted to go to school on Gielgud. As Taylor, the zaftig and improbable swami of Thorne’s tale, puts it, summarizing the stakes of the play, “The classicist who wants to be modern, meeting the modernist who wants to be classical. That’s where the fireworks begin.” But, in the Mendes production, that’s not where they end.

Gielgud and Burton may have been joined in a transactional theatrical purpose, but their personalities were dramatically at odds. Gielgud was a buttoned-down gay man of 60, all eloquence and restraint. (“I have always felt that Sir John Gielgud is the finest actor on earth, from the neck up,” the English theater critic Kenneth Tynan once said.)

By contrast to Gielgud’s mind and voice, Burton was all impulse and excess. He was 39 at the time, a whip-smart Welsh roaring boy, the 12th of 13 children, whose coal-mining father was, according to Burton, a violent “twelve pint a day man,” who, after his wife died, abandoned their three-year-old son to the care of one of his daughters.

“I am yesterday’s stale toast.”

Out of this roiling emotional deprivation, Burton emerged a prodigious boozer, womanizer, reader, spendthrift, smoker (100 a day), possessed of great physical and vocal powers. “He carries his own cathedral with him,” Tynan said of Burton’s generational talent.

So when the curtain comes up on The Motive and the Cue at the production read for Hamlet, Gielgud and Burton are at either end of the long rehearsal table with a star-studded Broadway cast between them. This staging foreshadows the battle of opposing forces: old order versus new; privilege versus working-class; gay versus heterosexual; repressed versus profligate; head versus heart. To a director as beady and successful as Mendes, these combustible ingredients also suggest the makings of a commercial hit.

Thorne’s narrative challenge is to give the large cast a wash of personality, while drilling deftly into the carapace of charm of his two extraordinary protagonists. It is inevitably a slow run-up to a powerful conclusion, which alternates between public rehearsal and private moments, which show Burton carousing at home with the cast and “Miss Tits,” as he called his wife, as well as a few scenes of Gielgud in agitated solitude.

If Thorne never quite gets Taylor (Tuppence Middleton)—he gives her respect but not dimension—or clinches the bonhomie of the sublunary theatricals, he nails the important central thing: the process of the actor’s struggle to claim the character’s meaning for himself. In this battle of wits, Thorne’s substantial accomplishment is to trap the sinew of both elusive theatrical giants.

As Gielgud, Mark Gatiss is an extraordinary incarnation of the theater director’s steely but hesitant aplomb. Tall and balding, Gatiss pads around the stage as erect, alert, and cautious as an egret stepping through marshes. He manages to make Gielgud’s silences as eloquent as his word horde. Gatiss doesn’t have all the good lines, but he has a lot of Thorne’s good writing. He gives a barnstorming performance of Gielgud’s strategic high-camp diffidence. “My only remaining ambition is to do an underwear advertisement … with me—sat in my intimates,” he confides to Taylor. “Saying, ‘At my time of life, all is quiet on the Y-front.”’

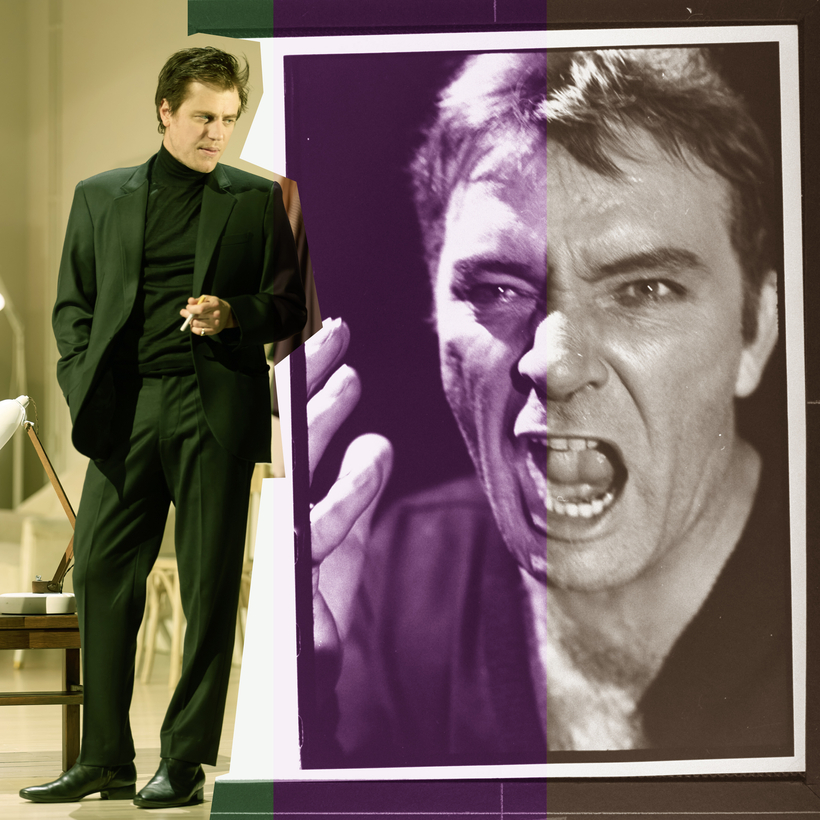

Johnny Flynn as Burton does well to stay toe to toe with Gatiss’s fancy footwork. He is in the unenviable position of having to portray a movie star whose image and charisma live in the popular imagination. Flynn has looks, swagger, articulate energy. But the coarseness that gave Burton his whiff of danger and rough allure, that tormenting shadow that is part of his particular voodoo has been bred out of Flynn’s polished being. Nonetheless, his portrayal has sufficient candlepower to make him a credible and effective adversary.

“We are all bullfighters,” Burton says to the company at the table read. At first, Gielgud turns out to be the bull who keeps knocking down Burton’s performance with his intruding notes. “Don’t you dare give me a line reading,” Burton says, smiling with cold teeth at his director. But behind Gielgud’s tentativeness is a tenacious attention to the text. He tries to tamp down Burton’s stentorian delivery and to get him to parse Shakespeare’s dense sentences more slowly so the audience can understand the progression of Hamlet’s gradual decision to take action against Claudius. “We must make sure all the passengers are in the carriage before driving it off the cliff,” he tells his balky star.

Gielgud presses for clarity, Burton for spontaneity. The result is percolating fury. “You’re not directing me, you’re directing yourself,” Burton blurts out to Gielgud, who drops his decorous politesse and socks it to his star. “You are going on the stage and giving them nothing but your bloated ego,” Gielgud snarls.

At the end of Act I, the tension has been built more or less expertly to a Mexican standoff when Burton arrives drunk to rehearsal, proffering scotch all around. “I’m so sorry to inform you of this, but I am afraid I am a professional,” Gielgud says, declining a sniffy put-down that allows the soused Burton to throw a show of coruscating cruelty. He taunts Gielgud as “note-giver,” does a limp-wristed parody of him acting Hamlet’s speech to the players, and tops his gross bully-boy display with a grace note of class hatred. “No need to get sensitive, John. Sorry. Sir John. Did I get the emphasis right? Sir John. SIR John,” he brays.

Gielgud clears the room. He stands alone in the large space, covered in humiliation and confusion. And in a finely devised moment, played by Gatiss with poignant restraint, Gielgud performs Hamlet’s great soliloquy—“Speak the speech, I pray you”—intended for Hamlet to the players, but now directly to us. The words, which have echoed down the ages, speak to the unresolved and brutal struggle in the rehearsal room. The last sentence—“They imitated humanity so abominably.”—hangs in the air like a curse as the curtain falls on Act I with Gielgud standing in silence and in tears.

Burton emerged a prodigious boozer, womanizer, reader, spendthrift, smoker (100 a day), possessed of great physical and vocal powers.

Directing is about timing and tact, and Gielgud can’t find the words or the way to capture his bolshie star’s imagination. (During rehearsals for the original Broadway production, Gielgud is on record as saying to Burton, “I’m sorry, Richard, shall I come back when you’re better—I mean, when you’re dressed?”)

Gielgud’s slips of unconscious aggression—known as “Gielgoodies”—were legendary; they point to the strategic psychological issue of tact in the theatrical process, which The Motive and the Cue expertly dramatizes. Enter Taylor, whom Thorne describes in the play’s cast list “as from another world”—the world, it seems, of literary devices. The louche sex machine of Act I turns out in Act II to be some kind of svelte deus ex machina, neatly providing the transformative clue to the flummoxed Gielgud. “He’s a miner’s son. A drunk’s son. He doesn’t understand diffidence,” she tells him over a breakfast meeting, adding, “You need to find a new way.”

Instead of arguing with Burton, Gielgud plays him like a fish, angling for Burton’s imagination by casting his disabusing thoughts lightly under Burton’s nose. “Your Hamlet is a bugle,” Gielgud says, slyly planting the notion that Hamlet might be ambivalent rather than furious about this father. “Could it be, have you considered—that your Hamlet does not like his father? … He was a cuckold. A weak man. You loved him, but he never gave you what you truly wanted in a King,” Gielgud says.

Burton toys with the bait, which Gielgud makes more tempting by first admitting his mixed feelings about his own father. “He was deeply average. Not the man I wanted to grow into. I was indifferent to him. But I loved him …,” he confides.

Gielgud’s admission of his own paternal bag of rocks winkles out into the open Burton’s punishing shadow: “My father was a bully, a drunk, and he left me,” he says. This moment of shared hauntedness, beautifully judged and written, ignites both their relationship and Burton’s attack on the role. When Burton attempts to recite Hamlet’s opening soliloquy, shading the words with ambivalence instead of fury, his character takes on a new gravity and grace. A lesson is being learned; a baton of craft being passed from one generation to another. The transformation happens before our eyes. Burton has found his way into the role and into himself—a moment as thrilling for the audience as it is for him.

When Thorne is dramatizing actors in rehearsal, he has a field day; in the private wisecracking scenes of the Burton-Taylor marriage, the writing occasionally hits still water. The propulsive rhythm of Mendes’s directing style—a fluid cinematic storytelling in which the scrims expand and contract, changing the size and intensity of what’s onstage—distract the eye and hurry the play over its narrative bumps. (The fluidity plays as “the passage of time” and also allows a fascinating overlap where the actors instantly shift from rehearsing Shakespeare’s words in private to playing them in the hubbub of the rehearsal room.)

Intimate moments are directed like a two-shot; rehearsals like a wide-angle; and, at the powerful finale, on the Broadway opening night, Mendes surprises the audience with a reverse angle: Burton launches himself upstage into the glare of spotlights. “Theater is bravery,” Gielgud tells Burton on the day of their last rehearsal. And in the play’s final beat we get a sense of the actor’s terror and elation—a leap every night into the unknown.

The moment is big magic: it brings the audience to its feet, from the stalls to the farthest reaches of the balcony. How can you explain a drama landing with this kind of wallop? It seems to go well beyond the expertise of actors. You could say that the play is a love letter to the commercial theater, or to the great stars who made it, or to the theatrical process of making meaning itself. All true enough. But it seems to me that the exhilaration and gratitude for The Motive and the Cue signal something else. The play honors actors as technicians of the spirit. The evening is a demonstration of something essential in theater’s enterprise: proof that the greatest show on earth is the show of human emotion.

John Lahr is a Columnist at AIR MAIL and the first critic to win a Tony Award, for co-authoring Elaine Stritch at Liberty