The only thing more subjective than individual taste in writing is that of the Swedish Academy. The Nobel Prize in Literature, out of wisdom or whimsy, has often favored esoteric writers, such as the African-born novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah (2021) and the Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek (2004). So it should come as no surprise that this year’s Nobel has gone to the French writer Annie Ernaux, who has emerged from out of the mists of relative obscurity (other than in France, where she has written best-sellers, and on these shores, where she has a cult readership) to take her place in the literary limelight.

Except that it does come as a surprise, if only because one thinks of the Nobel Prize as being conferred on writers who have carved out a terrain that is particularly their own, such as Alice Munro, but one that also functions as a comment upon the larger world. In some ways Ernaux has deliberately—and, one might say, daringly—turned her back on the whole issue of relevance; she writes quietly, almost without dramatic effect, as if into a journal (if one happened to be a uniquely talented journal keeper).

Someone who writes as autobiographically as Ernaux does naturally inspires curiosity about the life behind the scattershot information provided by her deliberately elliptical prose. Those readers eager to know more about her now have access to the ups and downs of her domestic life—her “family fiction,” as she calls it—and her beginnings as a novelist (she wrote in secret) with the release of a new documentary, The Super 8 Years.

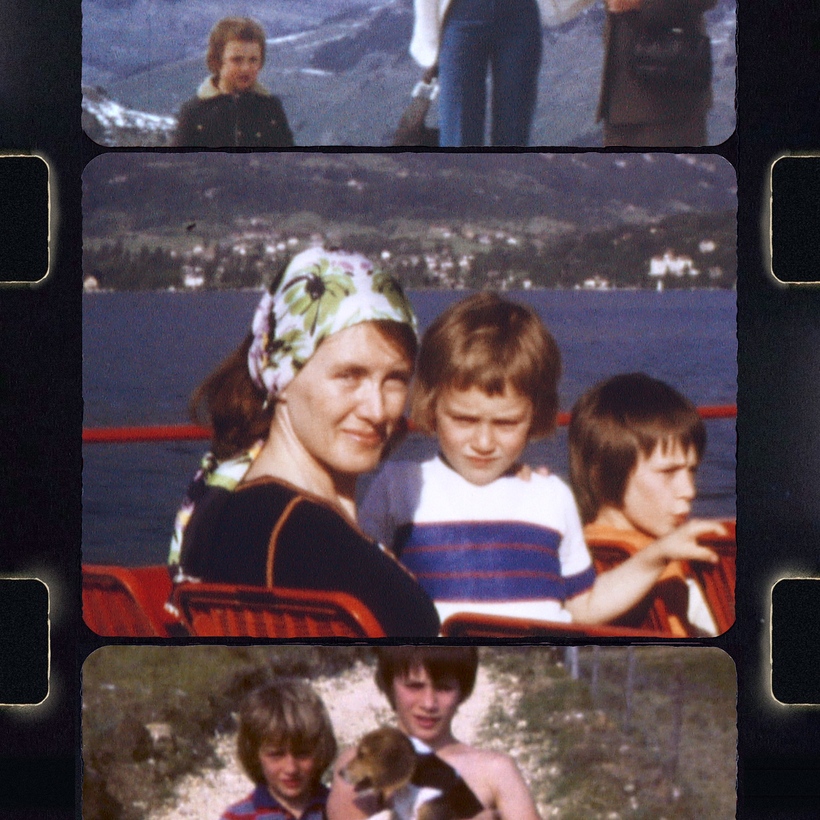

Made by Ernaux and her son David, the film is compiled from home movies shot by her spectral ex-husband, Philippe (who barely appears in the film), between 1972 and 1981, after he bought an 8-mm.—or “Super 8”—camera, which he began compulsively using. Ernaux supplies her own introspective voice-over, narrating both the frequent trips the family took abroad to Albania and Egypt, Spain and the U.S.S.R., in an effort to broaden their two sons’ perspectives, as well as the birthday parties and the bouts of chicken pox (or possibly measles) that mark their seemingly bourgeois existence.

“That summer Sunday, three-quarters of the way through the 20th century, in the shade of an amusement park,” Ernaux comments in her flat, uninflected way, over footage of a game of miniature golf, “time stands still before a rolling ball that you needed to position just so. In these silent images, bodies speak for themselves.”

Ernaux, who looks effortlessly chic in every scene (French women really do know something we don’t when it comes to tying a scarf and other fashionable touches), also looks distracted, almost absent. “The woman in the image,” she observes of herself, “always seems to wonder why she’s there.” Ernaux’s fine-boned face never shows much emotion other than a rare smile or two. (Then again, it must be noted that humor is not her strong point.) She is as merciless about herself on-screen as she is in her writing. About the gradual erosion of her and her ex-husband’s 17-year-long relationship, she says: “I’m superfluous in his life.” And she quotes a sharp admonition from her diary: “You mustn’t think about these things, old age and death, or you’ll lose all hope.”

In her fiction, Ernaux’s distilled and informal voice keeps circling her own life and the events that have marked it, particularly in the realm of obsessive erotic longing—which she calls “craving through absence” in Simple Passion, an early memoir in which she describes the aftermath of a love affair with a diplomat, a subject she returns to in her most recent book, Getting Lost, filling in some of the details.

Although one can read social commentary and political turmoil into her memoirs—or autofiction, as her work might be characterized (finally, a reason for this buzzy and vague term to exist!)—she is in the end incurably subjective, even solipsistic, someone who casts her net deeply rather than widely, in the belief that the treasure lies inside rather than outside the self.

I first read Ernaux in 1993, when I wrote a long essay about her for The New Yorker. I contrasted the diamond-hard, reticent prose of Simple Passion—her third book to be published here, after two short, unsentimental, but infinitely touching memoirs about her mother (A Woman’s Story) and her father (A Man’s Place), and still one of her best, along with The Years—to Robert James Waller’s The Bridges of Madison County and its equally schmaltzy follow-up, Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend.

In some ways Ernaux has deliberately—and, one might say, daringly—turned her back on the whole issue of relevance; she writes quietly, almost without dramatic effect, as if into a journal (if one happened to be a uniquely talented journal keeper).

Both of Waller’s mass-market books sold in the millions. Ernaux’s book, which was published by a tiny press called Four Walls Eight Windows, had evidently caused a stir in France, where it became a best-seller; although it sold fairly well here (in part, I was told, as a result of my essay), it was a succès d’estime rather than a commercial one. But then again, her books are too cerebral, too conscious of their existence as “texts,” and too interested in the ontological connection between different sorts of activities—sex and writing, say—to lure in a large American audience.

In the stories Ernaux tells, a woman is always waiting—for a phone call or a letter, or, as it may be, a visit. The passivity is deliberate, a prelude to the appearance of the real yet dreamlike lover, who eventually shows up, but always on his terms. There is something about waiting, the anticipation of what is to come, that stokes the flames of desire. “I’ve never written, though I thought I wrote, never loved, though I thought I loved,” declares the unnamed narrator of Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, “never done anything but wait outside the closed door”.

The women who write novels or memoirs about such characters—Ernaux, Duras, Edna O’Brien, Edith Templeton, Jenny Diski, and Jean Rhys, among others—are consciously depicting the women who are stand-ins for them in some way or other as impelled by a kind of willed helplessness, a wish to be the object of lust rather than the originator of passion. It speaks to the longing to be overcome, a position that is refuted and essentially disallowed in contemporary culture, where women are supposed to have put such power discrepancies—and particularly the longing for their enactment—behind them.

Ernaux’s Nobel Prize citation referred to “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” In both her writing and in The Super 8 Years, radical nostalgia—the memory of memories, an eternal redux—is what prompts Ernaux, a sense of the inherently conditional nature of things, their “will have been” quality. Her impulse is Proustian, although she doesn’t directly take on the society in which she lives so much as suggest it.

What interests her is who she once was, what the house looked like, the replacement of grocery stores by supermarkets, the smell of the sheets after sex—everything ending in a present that will do because it must. So Ernaux is not such an unlikely choice for the prize after all, because what she has to tell us in her slightly melancholy fashion is that everything, including the extremes of pleasure and emotional pain, passes, leaving behind the snapshots, home videos, and diary entries that can reveal, if one pays close enough attention, a fleeting glimpse of the truths that inform all our lives.

Daphne Merkin is the author of numerous books, including the memoir This Close to Happy: A Reckoning with Depression and the novels Enchantment and 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love