At Abba’s central London HQ, Bjorn Ulvaeus, 77, sits on a sofa, dressed head to alligator-skin, cowboy-booted toe in black. He is a picture of health, wealth and contentment. On the surface. In reality, he says, he wakes regularly in the wee small hours. Why? Oh, just the small matter of the opening of “Abba Voyage,” in two weeks’ time.

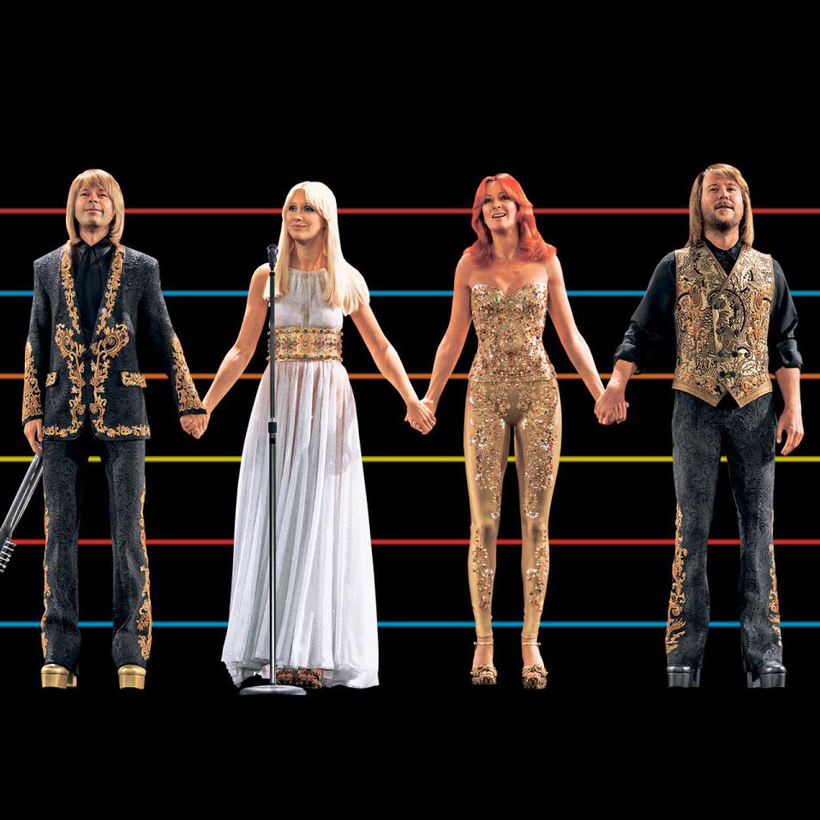

It is an immersive, “360-degree concert experience” where the band’s biggest, most popular hits will be staged in a custom-built, 3,000-seat venue at the Olympic Park in London. “Abbatars” — avatars of the band’s younger selves created with George Lucas’s visual effects company — will stand in for the septuagenarian original members and the 100-minute concert is booking until December 4, with multiple shows a week.

At an estimated cost of $18.5 million, the production is a significant risk, even for an act as commercially colossal — 385 million records sold, almost $4.9 billion in gross revenue for the musical Mamma Mia! and the two subsequent films — as Abba.

“No, it’s an immense risk,” Ulvaeus corrects me, “and most people I talk to don’t appreciate that. They say, ‘Oh, it’ll be fine.’ Sometimes I wake up at four in the morning and think, ‘What the hell have we done?’”

What they have done is devise a way of reinventing “live” music that could provide a template for heritage bands whose record sales have long since dried up, but who still haul themselves round the world, playing to crowds who only want to hear the hits they made in their twenties, in the Sixties, Seventies or Eighties.

The Throwback, Re-Invented

Speaking from his waterfront office and recording complex in Stockholm, Ulvaeus’s co-songwriter, Benny Andersson, 75, is acutely aware of what a game-changer “Abba Voyage” could prove to be — and how closely other bands will be watching to see if it is worth imitating (particularly those of a certain vintage or those who can no longer bear to be in the same room as each other).

“Lots of artists are going to be studying us, definitely,” Ulvaeus says. “I won’t name names, but I can think of a few. I wonder who’s going to be first.” The Stones, Led Zeppelin, surely, I say. Ulvaeus’s look is pure “I couldn’t possibly comment”. What about those bands known for their tempestuous relationships? “Oasis,” Andersson and Ulvaeus say.

Abba are known to have hated life out on the road. Anni-Frid (Frida) Lyngstad, 76, speaking from her home in the Swiss Alps, sees the “Abba Voyage” concert as a chance for them all to get some perspective on what they achieved at their height — without the tedium and fatigue that made touring an often miserable experience. “Our situation was so odd. Not in the studio, which was our second home, but going on tour, where we were more or less prisoners in our hotel.” No wonder the idea of Abbatars appealed.

“Abba Voyage” is a venture into the unknown. It could be a game changer, or a disaster, but given the band’s enduring global popularity who’d bet against them? The songs Abba released between their victory at the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest with “Waterloo” and their unofficial split in 1982 still soundtrack the lives of millions. With the exception of the Beatles, it’s arguable that no band’s back catalog has burrowed quite so doggedly beneath the collective skin.

And last year, after decades spent dismissing talk of a reunion, the band added to that catalog with Voyage, their first album since The Visitors in 1982. Full of harmonies and chord progressions that might have come from their heyday, it topped the charts in 17 countries, including Britain.

“The financial risk is not really only ours; there are other investors,” Andersson says. “Artistically, though, what are the risks? What are the possible criticisms? ‘Well, the band aren’t really there, are they?’ That’s the whole point. Will people accept that? Will they enjoy the environment, the great sound system? Above all it needs to involve emotions, and to me it does.”

The Sweet and Sour

Ah, emotions. I was at a wedding recently, and to watch a multi-generational crowd lose the plot when the introductory glissando heralded the arrival of “Dancing Queen” was to be reminded of just how ruthlessly effective Abba’s songs are at negotiating our neural pathways and penetrating our hearts and minds. Forests have been felled by scientists in their attempts to explain this.

Folk memory, emotion, repetition and communicative directness are known to trigger various hormonal shifts in our brains: a happy song induces a rush of dopamine, a sad one an infusion of prolactin. Abba manage to do both at once; the sweet and sour, the addictive salted caramel of music.

They have made their way into British politics too. When a party allegedly took place at the prime minister’s Downing Street flat last November, on the night of Dominic Cummings’s defenestration, guests reportedly danced the night away to “The Winner Takes It All” by Abba (an odd choice of song, given that it is about a breakup). Carrie Johnson, born in 1988, six years after Abba stopped performing together, loves the band.

Andersson’s eyes twinkle with mischief. “The media was calling it an Abba party. How could it have been? We weren’t even there. But anyone can play our music whenever they want to. What can we do? It takes all kinds.”

Agnetha Faltskog, 72, who scarcely ever talks to the press and declined to take part in this interview, once remarked, when asked what it was like to be on top of the world: “The air is cold up there.” Lyngstad acknowledges that she got the easier ride. “Agnetha had a lot of focus on her as the blonde, the angelic one with the beautiful behind. I was a bit in the shadow of that. But also I had the ability to lead a private life alongside my professional one. I’m not easily impressed by the glamour side of fame.”

Faltskog’s reaction to fame, especially after her divorce from Ulvaeus, with whom she has two children, led some to label her, inaccurately, as reclusive. She lives in Sweden, as do Andersson and Ulvaeus. Lyngstad, who rejoices in the title Princess Anni-Frid Reuss, Dowager Countess of Plauen, lives in Switzerland with her partner, Viscount Hambleden (a descendant of the family that founded WH Smith).

Lyngstad describes the period after Abba’s unofficial split in 1982 as “a case of finding new incentives in my career, and also in my private life, which was kind of daunting because both had come to an end after a decade. It was a very lonely process, a lot of soul-searching.”

Nonetheless, she didn’t hesitate when Andersson called her five years ago to get the band back together and record again for the first time since 1982. “We know each other so well. When we entered the studio we instantly fell back into the group dynamic.”

“We’ve always stayed friends,” Andersson says. “We’ve never had any arguments about anything in the past 40 years, I think. So that made it quite easy. Coming into the studio again, with everyone slipping back into their roles, it was like time had stood still.”

Ulvaeus says that they played the backing tracks a few times and went through the lyrics. “Then [Frida and Agnetha] went into the main room, put the lyric sheets on their stands, with the two mikes, in front of each other, as they always had. We wondered, ‘What will come out?’ They started to sing. Benny and I looked at each other. And there it was: the ‘sound’.”

But what about the aesthetic? The Abbatars will be wearing a succession of newly created costumes by Dolce & Gabbana, inspired by rather than recreating the fabulously outré and bizarre outfits the band were famous for in the 1970s. “The white dungarees are not there,” Ulvaeus says. “You can stay calm.”

“Coming into the studio again, with everyone slipping back into their roles, it was like time had stood still.”

“Actually,” Andersson says, chuckling, “I think Bjorn’s worst one was that Superman-style outfit.”

“He had those weird body stockings too,” Lyngstad says. “But there are some really over-the-top costumes in the show too. Why not? It would have been odd to transform our flamboyant side into something safe. That wouldn’t be us, would it?”

She and Faltskog have yet to see the show. “We’re waiting until the premiere. I want to be surprised, to be happy and sad and all of those things, all at the same time.”

It has been a 40-year wait, but it will be worth it to come as close as possible to experiencing Abba live (if not quite in the flesh), performing some of the most perfect and imperishable music of all.

“Pop,” Ulvaeus says. “Pure pop. That’s what we strived for. Every note, every word where it should be.”

The world awaits. To paraphrase the immortal “Dancing Queen”: we will dance, we will jive. But will we have the time of our lives?

“Abba Voyage” opens on May 27 at the Abba Arena, in London

Dan Cairns is a music editor and features writer for The Sunday Times