I arrive at the front door of Bono’s art-filled house in Dalkey, South Dublin, the city where we first met as teenagers, brandishing a gift: a first edition of The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov’s dissident Stalin-era satire about the Devil trailing fire and chaos through Moscow.

“How did you know? It’s my favorite,” enthuses the black-jeaned, rose-tinted-spectacled icon, whizzing me off to admire another recent acquisition, a portrait of the poet Seamus Heaney by Colin Davidson, before we set off for a late afternoon Guinness at his local pub, Finnegan’s.

Sundays chez Bono are open house and not for the faint-hearted. The last time I was here, before the pandemic, lunch for eight around his lengthy dining table (it could comfortably fit a UN delegation), overlooking his tousled garden and the gray-green sea of Killiney Bay, morphed into an all-day conversational orgy at Finnegan’s. There, we built up a salt ’n’ vinegar crisp mountain: 30 empty packets, counted out painstakingly by Bono and my husband between pints.

At some point our bored kids had to be rescued and dropped back to our hotel by the ever-responsible U2 guitarist Edge and his wife. (“Who was that nice man in the beanie?” they asked the next morning.) We, the dregs, lingered until closing time solving the world’s woes to our inebriated satisfaction.

Two years later I’m back to celebrate the imminent release of Bono’s literary debut, his memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story. Normally he can move around his neighborhood with ease, although this time our meander down the hill to Finnegan’s is interrupted by a fan requesting a selfie. Bono is effortlessly charming, smiling for the camera with no indication that it’s possibly the millionth time he has been asked.

In the snug of the pub, he’s free from the glare of the big wide world — and perhaps that’s the reason he has remained on the “small rock in the North Atlantic” on which he was born, married to a girl he first asked out in 1976. The 62-year-old star lives in his hometown with “the love of his life”, Ali Hewson, née Stewart, 61, whom he met in the same week that his band got together —schoolmates who remain his best friends.

Bono and I first met at a tiny recording studio called Keystone, in Harcourt Street, Dublin, when I was 15 and trying to chase away the pain of the early death of my father, Peter, by ditching school for a music business apprenticeship. Bono was 18 and had lost his mother, Iris, four years earlier. She had collapsed at her own father’s funeral in 1974 and died from a brain aneurysm a short time later, leaving Bono and his older brother, Norman, with their father, Bob, a postal worker.

Perhaps it was our unexplored grief that bonded us. As U2 — the four-piece band Bono formed with friends at Mount Temple Comprehensive, one of Ireland’s first nondenominational co-ed high schools — recorded their first demos, I rustled up tea and stuck recording tape together. Despite irregular reunions, we’ve never lost our connection.

Back then, U2 were a post-punk band and, by Bono’s admission, magnificently awful (having witnessed their first gig in Dublin in 1978, I concur). But that quartet — Bono on vocals, David Evans (“the Edge”) on guitar, Larry Mullen Jr on drums, Adam Clayton on bass — went on to sell more than 170 million records, redefining stadium rock in the process with their soaring anthems such as “Beautiful Day,” “Where the Streets Have No Name,” and their most political song, “Sunday Bloody Sunday.”

Now comes Bono’s autobiography — a chunky tome, beautifully evoked, a mixture of Joycean exuberance and Chandleresque irony. In it, he has revealed headline-making details about the IRA death threats he received after the Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams criticized his anti-paramilitary stance; how Dublin gangsters plotted to kidnap his daughters; and how the Pope once tried on his trademark tinted specs (which he wears because of glaucoma). But most revealing are the intimate personal experiences that shaped him and his chaotic creative process.

Perhaps it was our unexplored grief that bonded us.

Punctuating it all is the music. Each chapter uses a U2 song to pull us down memory lane. “It’s actually like 40 short stories, really,” he says, “so you can dip into the bits that are interesting — although I’d like you to go from beginning to end because I worked very hard at that arc.”

It’s difficult to find someone among my generation who doesn’t have an opinion about Bono — a star both lauded and mocked for his earnest devotion to social justice activism. But whatever you think of him, it’s unlikely he hasn’t thought it about himself.

Before my visit he sends me a self-deprecating list of alternative titles for his memoir: “40 Tall Tales from a Short Rock Star” (he has always been self-conscious about his height, describing his 18-year-old self in the book as “an apprentice rock star of five feet seven and a half who swears he’s five feet eight”); “The Baritone Who Thinks He’s a Tenor” (a jibe his amateur opera-singing father used to make); and “The Pilgrim’s Lack of Progress” among them.

He is, he admits, a salesman. Early in his teens he got the branding right. Born Paul David Hewson, he embraced the moniker bequeathed to him by another childhood friend, the artist Guggi — taken from a local hearing-aid store called Bonavox. The Latin, good voice, was shortened to Bono and a star was born.

The book opens not with the roar of the crowd but the ambush of a silent killer. Bono was born with an “eccentric heart” — “in one of the chambers of my heart”, he writes, “where most people have three doors, I have two”. The weakness revealed itself in December 2016 when a blister on his aorta was about to burst, requiring life-saving surgery in New York City.

A near-death experience is a decent excuse to look back on your life, I suggest.

“I don’t know how long I’m going to be around,” he replies, “and when you have an experience like that it reminds you … I’m totally at peace as far as …” he trails off, but quickly returns to the music. “I don’t have the obvious fear of death, but I’d like to write one more proper balls-to-the-wall, unrelenting, noisy rock ’n’ roll song.”

Despite his success, he has only occasionally become distracted by the Pandora’s box fame opens. He describes a period when he nearly lost himself. “I’ve always felt like a sort of impersonator when it came to being a rock star, like I couldn’t quite fit the bill. But in the Nineties I might have gotten a little too good at it. I suppose I could have stayed in those plastic pants,” he says, referring to his faux-leather trouser look. Campaigning rescued him. “I would say that what people call [me] ‘saving the world’ was probably me saving my own ass. I think the betrayal would have been to just enjoy this — the fabulousness of finally becoming rock ’n’ roll people.”

I didn’t see much of him during that decade, though we bumped into each other after a couple of years’ hiatus at the Ivy, in the London restaurant’s heyday, where I was having dinner with a girlfriend. I’d never seen a jaw actually drop, until hers landed in her Caesar salad when Bono appeared at our table and announced that he’d been in love with me since we were children. Not, of course, the case: that honor befell Ali — but it was hugely flattering, especially given that he’d left Bill Clinton perusing the menu alone.

Two decades on, settled into our favorite corner of Finnegan’s, where Bono’s previous guests have included Michelle Obama, Mel Gibson and Salman Rushdie, I’m interested to know what drove him to write a book that will inevitably lead to increased attention on his personal life. “Yeah … it’s not a confessional,” he says. “I think it goes deeper than that. It’s more anatomical — the anatomy of songs and the songwriter. An activist. A megalomaniac. A pilgrim. The man who won’t leave the bar till he’s asked to.”

It’s difficult to find someone among my generation who doesn’t have an opinion about Bono.

The latter feels like a warning based on experience. He continues: “I understood that I had my fists up metaphorically, and sometimes literally, for most of my life. I’m just a combative person. I go after things. And I needed to learn more to let go of things. I partly wrote the book to explain to myself and to anyone who was interested that it was OK to have these different lives. That they weren’t contradictory. That you could be an activist and an artist. Building organizations like ONE or (RED) [the two campaigning organizations he has spawned] — I saw them as songs. They’re kind of beautiful constructions.

“I also wrote the book to explain to my family what I was doing with their life because it was they who permissioned me to be away with U2 or lobbying Congress. Ali gave me the chance and covered for me at home. So I’m not writing a rock ’n’ roll memoir, [or] an activist’s memoir, I’m not just writing a sojourner’s memoir, I’m trying to write a love letter to my wife.”

In that endeavor he has succeeded. What sings pure and true from the pages of Surrender is the importance of his 40-year marriage to Ali, with whom he has four grown-up children: the actress Eve and the activist and budding musician Jordan, born at the turn of the Nineties, and the millennial boys, John, currently at college, and Elijah, the energetic front man of the rock band Inhaler. Through ups and downs — hinted at but unelaborated on in the book — his and Ali’s bond has endured. How have they made it work for so long?

“Look,” Bono says. “She’s incredible. She’s not just a mystery to me, by the way. She’s a mystery to her daughters, to her sons. I mean, we’re all trying to get to know her. She’s endlessly fascinating. She’s … full of mischief.” He doesn’t paint over the cracks entirely: “It’s not like our love was absent any dark undercurrents or briny water, [but] we got each other through those bits where it was hard to see where we were. Ali calls it ‘the work of love’. I wish she wouldn’t use the word ‘work’ because I have a feeling there’s an adjective, ‘hard’, that’s inferred.”

Was he nervous about dragging their relationship into the daylight?

“My story is her story. And it’s a love story. She was, like, ‘It makes it a little public between us, so spare me the sentimentality.’ ” In the book he quotes her once telling him: “Don’t look up to me or down on me. Look across for me. I’m here.” That line, he says, “still takes my breath away. That’s who she is. So she knew there’d be some briny water — when you’re down at the bottom of the sea, you can’t stay for too long, you have to surface. And we did. If one of us got lost the other was going to get us back, that’s kind of been the way it’s been for us. I think in relationships somebody is in charge at some point, but you swap. It’s a relay race.”

Still, four decades of nonstop touring and absence, hanging out with supermodels at parties and campaigning across the globe would be a strain on any relationship.

“The significant thing about Ali was she was never going to be ‘her indoors’,” he says. “She was never going to be just my girlfriend and she was never going to be just my wife. So if I was home I’d better be present. And in the Eighties at some point I was home but I wasn’t present. And that’s when I think she wanted to jump. Both she and Edge, who are very close … will be your most loyal friend ‘till death do us part’. But they both look at me with the same look, which is, ‘Don’t let me down’.”

“I’m not just writing a sojourner’s memoir, I’m trying to write a love letter to my wife.”

He tells me about their 40th wedding anniversary. “We were sitting at the table and talking about our getting married when we were only children — she’d had this whisper in her ear which was, ‘Your freedom will come in your marriage.’ Which is an unusual thing! And I think it’s really been true for both of us. And the stuff that Ali wanted to do, whether it was go back to college or fly airplanes or even the Edun stuff in Africa [Ali is the co-founder of two ethical businesses, the Edun fashion line and Nude Skincare products] — I’ve tried to make sure that the family wasn’t just working to realize my vision but hers too.”

Incredibly, they have retained a private life, which he puts down to his community. “I think Ireland saved us from ourselves — though I’m not sure it’s good for Ireland because we have an old problem … which is we can look down on success. I mean, you’ve seen it. In this pub where we are sitting, you’d better be funny, because it doesn’t matter how much you’ve got in your back pocket, they just yawn in your face. So I think Ireland really helped.”

He’s clearly proud of the country’s evolution into a successful, outward-looking European nation. “A tiny rock in the Atlantic, beaten by bad weather and sometimes badly behaved neighbors … Our natural resources were really an educated, ambitious people, made more so by the stories of their cousins and relatives who’d emigrated across the world. And the stories they brought back. So Ireland has become cosmopolitan.”

As a campaigner for eradicating global poverty he’s less impressed with the UK — especially about reneging on its 0.7 percent commitments for international development. “We miss the leadership from the UK so much. The UK had this moral force that came with it because both Conservative and Labour leaders committed. Coming out of Europe is one thing, but coming out of the world? I don’t believe that’s what the people of Britain want for their country.” It’s as close to a political statement as he’ll get.

He might say that Surrender isn’t confessional but it feels that way, and illumination often comes in the spaces left. There’s a deep seam of grief and tenderness about his mother, Iris, throughout. “My brother, Norman, and I have very few memories of my mother because she wasn’t spoken about,” he says. “It was just too painful. We simply stopped talking about her. So she disappeared.”

One story in the book highlights that emotional shutdown. The band are in a rehearsal room next to the graveyard where Iris is buried, arguing while writing “I Will Follow,” a heartrending cry to a lost love. “It’s about a kid who’s going to follow his mother into the grave. It’s a suicide note,” Bono says. “And not one of us stopped to think that Iris is a hundred yards from where we’re having this argument. And I had never visited her grave. While rehearsing right beside her! How mad is that?”

He speaks with affection about Iris and compares her to his wife. “She was very practical. She made clothes, she could change a plug on a kettle, that kind of thing. Ali is kind of similar. If she had to figure out how to not just fly an airplane but build one, she would.”

And yet he writes about his mother like a romantic heroine, with laughing eyes and curly black locks, and you can feel the tumultuous emotion of the bereaved boy. The process of writing brought Iris to the foreground again.

“It was beautiful to write my way to her and to find her. The memories were so joyous, all of them. Her trying to discipline me and our neighbor says, ‘Yes, use a cane.’ And she’s chasing me down the garden and I’m terrified — she’s got this weapon. And I look around and she’s just laughing. She can’t take it seriously at all.”

There’s clearly a strong connection between the loss of his mother and the entrance of the love of his life shortly afterwards, and he doesn’t deny this.

“The spirit of creativity is so feminine. And if you don’t have it in your life, it’s that void you’re trying to fill. And Ali, for sure — there was some handover of responsibilities, but it is unforgivable for a boyfriend to try and turn his girlfriend into his mother. I wouldn’t have gotten away with it if I’d tried. But there was some transference of that feminine energy.”

His relationship with his father, Bob, became troubled after his mother died. “Already you’ve got a lot of [teenage] ‘hormoning’, which couldn’t have come at a worse time for the old man and me. The house became a less safe space for both of us with me squaring off with him. It’s as old as the elks. You’re just locking antlers.”

The tensions at home were given more context in September 2000 when Bono’s brother, Norman, called him to reveal that their cousin Scott was actually their half-brother. Bono’s father had always been close with his wife’s sister-in-law.

“I think I knew, subliminally. Because the phone rings and my brother says, ‘You’d better sit down. I’m going to tell you something that you’re just not going to believe about our da.’ And I said, ‘What? That my cousin is my brother?’ And he goes, ‘What?!’ So, I don’t know. I must have.”

Bono tells me how his friend Jim Sheridan, the My Left Foot filmmaker, once gave him a “genius” psychological insight into how becoming a rock singer may have stemmed from his fury with his father (the frustrated opera singer). “It’s all right there,” Sheridan told Bono. “What does the da want? He wants to be a singer. So you want to take this love away from him, because something in you believes he took your love — your mother — away. It’s revenge. It’s a kind of patricide. Something inside you blames him on the death of your mother.”

“And I’m, like, ‘No way, I don’t blame him,’ ” Bono says. “But Jim says, ‘No, no, that’s not how human psychology works.’ ”

It was an epiphany. Bono recalls moments of reconciliation over the years, including turning a spotlight on his dad in 1985 in Houston, when he was standing by the mixing desk. “I introduced him from the stage, ‘Here for the first time in the United States, here for the first time in the Lone Star state of Texas … my father, Bob!’ And one of the Super Trouper spotlights goes on! The whole arena can see him. And he just stood up and was, like … the hard man. But afterwards he came back and he looked a bit shook and I could see his eyes were just a little red. And he put his hand out and I put my hand out, and I’m [thinking] here it is, I’ve been waiting for this my whole life, my father is going to tell me I have arrived as a singer — and he says with casual gravitas, ‘You’re very professional.’ ”

By the time Bob died of cancer in 2001, “we were close enough friends for me not to feel abandoned”, Bono writes.

With Bono’s own son Elijah now touring the UK with his band, Inhaler, I ask how supportive he is of that career choice, whether he’s worried U2 will always eclipse Elijah’s ambitions? There’s a flicker of that historic father and son competitiveness. “Inhaler are properly great — but let’s not make it too easy for him. Come on!”

In Surrender Bono often refers to his sense of insecurity, but when I quiz him about it he leans forward, eyes a-twinkle, and confesses with a grin: “This insecurity thing … I’ve realized recently it’s only skin deep!” And we both burst out laughing. Bono is a man imbued with boundless self-awareness but often the inverse ability to employ it as a mitigating influence.

Back at the house he plays me samples from the audiobook of Surrender, “the Sgt Pepper’s of audiobooks” he announces with glee, telling me he has reinvented the form. Thing is, he’s right: it’s scattered with blasts of music from U2 to Dylan and the Undertones and his hard-boiled detective delivery. Another man might have let others proclaim its brilliance, however.

It reminds me of a night a couple of decades ago when he turned up at a dinner hosted by our mutual friend from 1970s Dublin, Bob Geldof. It was an intimate gathering of eight held for the prime minister, Tony Blair. Bono had initially declined due to recording commitments, but late in the evening the doorbell rang and he burst into the living room carrying a ghetto blaster and a demo tape. He had a new U2 song to play the PM. Geldof, who’d stumped up the lobsters and fine wine, could only sit back and take second place as Bono took the floor. Everyone laughed at his audacity. He may dance to his own tunes but when you look at what his chutzpah has achieved, it’s hard to be judgmental.

Like Geldof, the impact of Bono’s campaigning is unprecedented. To date, his organization Red has raised $700 million for Global Fund grants in support of HIV/Aids programs and more recently Covid-19 response, benefiting more than 245 million people. As the millennium approached he ran with Jubilee 2000, a germ of an idea from a coalition of campaigners to drop the debt owed by the world’s poorest nations. In 2018 the World Bank announced that 37 countries had been relieved of more than $100 billion of debt. As a result, “the World Bank estimated that an extra 50 million children were able to attend school”, Bono writes.

I brought him the Bulgakov novel because if I were to liken him to any character in literature, it’s Behemoth — the Devil’s black cat — stirring mischief and creative chaos about him, darting between sold-out stadiums and UN congresses, between pop-up gigs in Ukraine and the beleaguered inhabitants of Sarajevo, with plenty of playtime in between.

“It’s revenge. It’s a kind of patricide. Something inside you blames him on the death of your mother.”

The guest bathroom in his house bears testament to his roving interests. It’s an autograph hunter’s Nirvana. Graffitied walls bear the signatures and pocket wit of authors (“I still haven’t found what I’m looking for but this comes pretty close,” Salman Rushdie has scrawled), presidents (“A and B = C” is one enigmatic example left by Bill Clinton), musicians (“I write between the cracks” — Michael Stipe) and architects (Tadao Ando left a drawing that takes up more than its fair share of wall). Is he a fanboy despite his status? “They’re just people. You can pick a book off a library shelf and you’re in the company of somebody who’s really spent time thinking through some things. What a joy that is! So let’s say I’m interested in the climate crisis and I get access to a climatologist because I’m the singer in U2, I’ll take it. I could read their book, but instead I’m in their company physically.”

Cooperation between unlikely partners is a trademark of his activism. But his ability to harness the high note in a campaign and use it to unify and broker interest from all sides of the political fray whiffs of Mephistophelean genius.

“The heart of my life as an activist was really saying I don’t have to just come from the left, which I was traditionally born into. I can cross the aisle.” It’s “a multi-personality disorder”, he admits, “but I’m not just swerving all over the road … I’m not a dilettante, I get to grips with the terrain.”

He has recruited some strange bedfellows to his campaigns, whether anti-abortion evangelists like Jesse Helms or Republican presidents such as George W Bush. I ask when he has felt most uncomfortable.

“I do remember the nauseating sinking feeling of being in Genoa at the G8 [in 2001] when a protester, Carlo Giuliani, was killed. There were two photos on the cover of an Italian newspaper the next day — one of the fallout after the shooting and one with me smiling with Tony Blair and Vladimir Putin. This was before Putin had become officially evil. He’d made a joke about whether I and Jubilee 2000 could help with Russia’s debt service. And I laughed and he laughed. And that was the shot. That was very hard for U2 to see. You know, there’s this pitched battle on the streets of Genoa and there’s the singer of their band having his back slapped. It’s not a good look.”

Some bandmates feel it acutely. “Larry would be very critical of the company I keep,” he says. “Fame is the currency I want to spend in all these other areas; he’d rather stay away from everything else and just focus on the music, on being in a band.”

Can’t Larry take that path if he chooses?

“He can, but he’d rather I did too!” Bono grins. “It’s much more glamorous to be on the barricade with the cloth over your nose and a Molotov cocktail. I mean, that’s a great look for a rock ’n’ roll band. But to be on the other side of the barricade, having conversations with the Establishment figures, less so. But if that’s what it takes to win the day for people whose lives literally depend on you winning the day, that’s OK.”

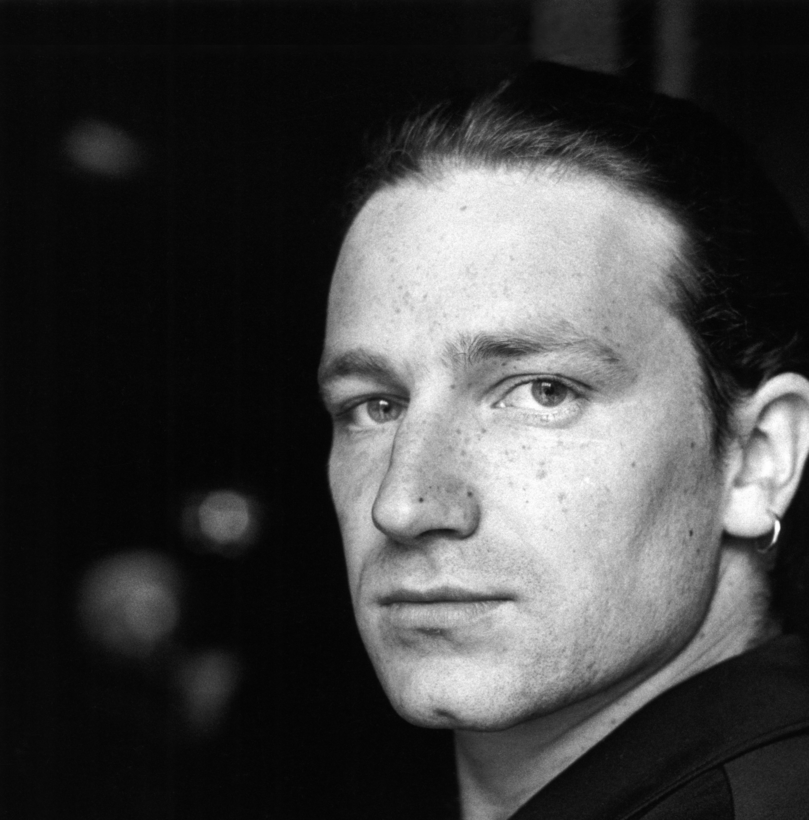

At the back of the book is a scattering of old photographs. Looking at the mullet-topped, mesmeric gaze captured when he was 18, I’m struck mainly by how little he has changed from when we first met.

He sweeps into every room in a burst of demonic energy, poking and provoking, exhausting and inspiring. No wonder Ali heaves a gentle sigh of relief waving him off the next morning as he rolls his bag out the door to attend the UN General Assembly in New York, meet President Zelensky, erase global poverty, visit the Pope, slip on those “plastic pants” for another gig or embark on a rumored residency in Vegas. Once he has departed, Ali and I take a hike with the dog up Killiney Hill and back to normality.

He begins the book trying to make sense of his fists-up-to-the-world stance. At the pub I asked if he’d got that out of his system. “Making peace with yourself or making peace with your maker is a very different thing from making peace with the world,” he replied. “I am not ready to make peace with the world. In some senses you don’t want to put your fist down. Defiance is the essence of romance. That’s where rock ’n’ roll comes in.”

As we extracted ourselves from our cozy corner, the burble of Finnegan’s making it harder to hear his low, persuasive voice, I asked what ambition he had left. He was characteristically expansive.

“To be famous for your songs is where I’m getting to. I wanted to be famous for being in U2, and then I wanted us to be famous for what U2 could do outside of music. Right now, I just want to write this f***-off rock ’n’ roll song, the like of which no one has ever heard, and hear the roar as it sails over roofs of stadiums. And I wanna be singing, dancing, shouting at God with U2 fans in a big festival field in the rain — and not making it so easy for the next generation of guitar bands.”

Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story is available now from Hutchinson Heinemann

Mariella Frostrup is a British journalist and a presenter of a weekly program on Sky Arts, The Book Show, as well as Open Book, on BBC Radio 4