Françoise Gilot, the only woman who left Picasso, decided to be an artist when she was five years old. She was living in a suburb of Paris at the time with her father, an agronomist and businessman who wanted Françoise to be a lawyer, and her mother, a talented watercolorist.

As Gilot grew up, she studied art history and visited museums. She graduated from the Sorbonne with a degree in philosophy, received a degree in English literature from Cambridge University, and enrolled in law school but eventually abandoned it and became a successful artist.

At 99—she turns 100 in November—Gilot is witty, articulate, and laughs easily. We meet in an apartment with a large studio off of Central Park West that she has occupied for more than 30 years, splitting her time between New York and Paris. She stopped painting two years ago.

“She is amazing,” says Dorothea Elkon, her close friend for 60 years and her New York dealer since the early 90s. “She has so much energy and remembers everything.”

“Because of her memory, when she was in high school and at university she was known as the Little Encyclopedia Britannica,” her daughter Aurelia Engel adds.

Picasso told Gilot that she was “headed for the desert” because no one would have anything to do with her after she left him, in 1953, 10 years and two children after the pair first met. Following their split, Picasso reportedly told dealers not to work with her.

Yet Gilot’s works have been exhibited throughout the world in more than a dozen museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. She has produced more than l,600 paintings and 4,000 to 5,000 drawings and prints, and the prices for her work have been rising.

A Gilot exhibition is now on at the Estrine Museum, in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France. Other shows of her work are scheduled to open later this year at Galerie Patrick and Jillian Mac Fine Arts, in New Orleans, and at Várfok Gallery, in Budapest. Christie’s is planning an auction of Gilot’s work in Hong Kong in November.

“Her prices have been blossoming slowly but steadily,” says Holly Braine, head of day sales of Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby’s in London. “It’s one of the steepest curves in accelerating values of all the artists we deal with.”

Last May, Gilot’s painting Paloma à la Guitare (1965), a portrait of her and Picasso’s daughter, sold for $1.3 million at Sotheby’s in London, seven times its high estimate. Her previous record auction price was $695,000, paid for Étude Bleue, a 1953 portrait of a woman, at a Sotheby’s sale in New York in 2014.

The most expensive Gilot paintings are usually said to be the ones she made when she lived with Picasso. They range from $150,000 to $500,000.

Paintings after 1953, when she left him, often range from $15,000 to $80,000. In the mid-1990s, prices for those paintings were $10,000 to $20,000.

Patrick Weathers, a private dealer who operates Galerie Patrick and has been selling Gilot’s art at the Mann Gallery in New Orleans, says her works on paper that sold for $7,500 to $8,500 20 years ago are up to $150,000 today.

Picasso told Gilot that she was “headed for the desert” because no one would have anything to do with her after she left him.

Gilot had already had an exhibition in Paris and was selling her work when she met Picasso at a restaurant there. She was 21; he was 61.

Their son, Claude, now heads the Picasso Administration in Paris, which handles reproduction rights and the marketing of Picasso’s art and name. Paloma has been a jewelry designer for Tiffany & Co. since 1980.

One of Gilot’s books, Life with Picasso, which became an international best-seller after it was published in 1964, infuriated Picasso. She portrayed him as loving and brilliant but tyrannical and a monster. Picasso tried unsuccessfully to stop it with three lawsuits and a manifesto to ban the book signed by 40 French artists and intellectuals.

After leaving Picasso, Gilot married twice, first to Luc Simon, a French artist—their daughter, Aurelia, is an architect and manages the Gilot archive—and then to Jonas Salk, who developed one of the first successful vaccines against polio. He died in 1995, after they had been married for 25 years.

I interviewed Gilot recently while she was sitting on a couch in her studio with her daughter Aurelia, who occasionally served as interpreter when Gilot replied in French to one of my questions. We talked about many artists, but Picasso’s name did not come up in our 90-minute conversation.

Many of Gilot’s paintings were leaning against a wall to our side, while others hung elsewhere in the studio. There were many books about artists in the apartment, including Modigliani, Soutine, Mary Cassatt, Georgia O’Keeffe, Rembrandt, Frida Kahlo, and Balthus. In addition, there were volumes by Shakespeare, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Arthur Koestler, and Italo Calvino, among others.

There were some books about Picasso but no works by him. Gilot sold the only one she had, a portrait of her from his “La Femme-fleur” series, to a private collector many years ago. Neither Elkon nor Aurelia knows how much she sold it for or who bought it.

Gilot had a still life by Braque, whom she met, in her living room. She also met Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Nicolas de Staël, and Jean Cocteau. She claims she was influenced by many artists but “no one in particular.”

In her 1986 book, An Artist’s Journey, Gilot wrote that, as she looked back, “all the canvases that I created are the milestones of a pilgrimage, a hymn to the diversity of experience and the unity of life.”

I asked her to elaborate. “I painted because the human body has a large possibility of expression,” she said. “Nobody has the full spectrum of experiences. We all have pieces of experiences. There are as many experiences as there are people. We are not obliged to like all artists. A work of art will resonate with some people and not others.

“My mother taught me how to draw and to try to put yourself into the unknown, to jump into the void,” Gilot continued. “I build castles in the air because of my work as an artist. Sometimes I live in them. This is more satisfactory than a real mansion with defective plumbing. I don’t need possessions.”

A critic once said that Gilot’s art “moved freely between abstraction and representation and between landscape and figure subjects.”

“When I was a young artist,” she told me, “I belonged to a movement that only did abstraction. I left. I wanted to go where my mind and heart had to go. You don’t have to repeat something that has been said. You always want to try something new, something that is beyond you. I think it is more important to be true to oneself than to follow the currents.”

I asked Gilot why she continued to paint for nearly eight decades. “Art is mysterious even to the artist. When you work you are on a path of discovery. You get a feeling that will transport you in a way that is not rational.”

Gilot loved the works of Van Gogh when she was a child. “I still do,” she said. “When I discover something, it is once and for all. It stays in my heart.”

“Françoise Gilot” is on now at the Musée Estrine, in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France

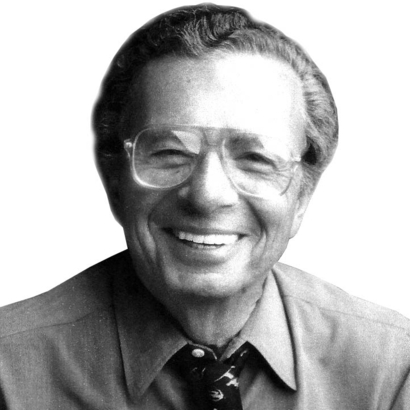

Milton Esterow was the editor and publisher of ARTnews from 1972 to 2014. He currently contributes to The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair