“Hang on to your publishing.” When I was playing in rock bands around New York City in the 90s, during the brief gold rush that followed the success of Nirvana, that was the mantra of every manager, lawyer, and songwriter I ever encountered. There was, of course, the coveted publishing deal that let you quit your day job—a trade-off that saw friends in bands selling their songs and writing new ones for the latest would-be sensations. But there were other friends in other bands whose moderate alt-rock hits proved to be lifelong revenue sources that topped up their bank accounts with every radio play, licensing opportunity, and needle drop in a Hollywood movie. One guy I knew scored a mid-chart hit, and then quit his band, married a starlet, and effectively retired before turning 30. This was the power of owning your songs. Since you’re asking, I did hang on to my publishing. Not that anyone ever asked for it.

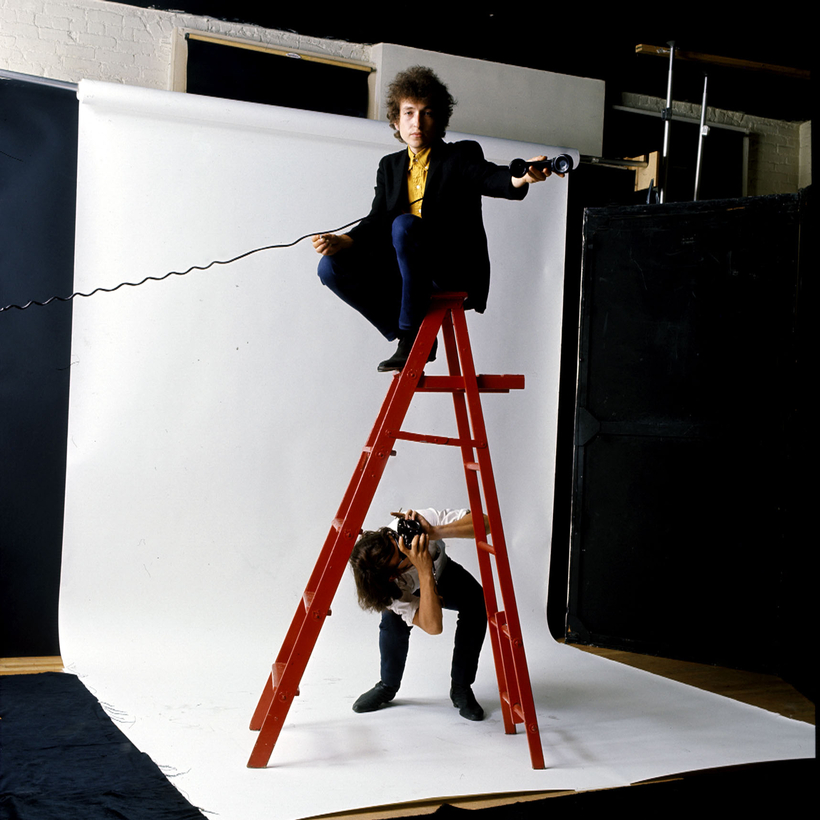

Lately the old wisdom has been turned upside down. In December, Bob Dylan sold his catalogue to Universal Music; the undisclosed price was conjectured to be more than $300 million. In January, Neil Young sold a 50 percent stake in his 1,180-song catalogue to the upstart Hipgnosis Songs Fund, an investor-driven outfit founded by Merck Mercuriadis, the former manager of Iron Maiden, Elton John, and Guns N’ Roses, for reportedly around $150 million. In February, the Beach Boys sold a controlling interest in their intellectual property, which includes master recordings, a chunk of publishing, and a brand that is practically the rock ’n’ roll equivalent of Coca-Cola, to Iconic Artists Group, a new company established by the industry panjandrum Irving Azoff, who has managed the Eagles, Steely Dan, and Jimmy Buffett. The price was not revealed, but the Beach Boys’ musical assets have been estimated to be worth as much as $200 million. And then, in March, came the sale of Paul Simon’s catalogue to Sony; the monetary terms—no doubt staggering—were not revealed.

The Rolling Stones once sang, “It’s the singer, not the song.” But, according to Mercuriadis, “the song, even more so than the artist, is the most important component in a hit record.” The growth of Hipgnosis exemplifies the trend of catalogue acquisition, and has arguably driven it. In the summer of 2017, when Mercuriadis’s company was getting off the ground, the start-up targeted approximately 1,005 songs for purchase. A prospectus identified artists such as Beyoncé, Justin Bieber, Adele, and Kanye West. The brief: attract investors, use the funds to buy song catalogues (at, say, 15 to 20 times their annual revenue), and then I.P.O.—a Silicon Valley–style “get big, right now” strategy. Hipgnosis went public the next year, raising $800 million. Two years after that, the company owned 12,000 songs, from such artists as Al Green, Blondie, and Rihanna, with acquisitions totaling about $1 billion. “I want to own the very, very best and the most culturally important songs,” Mercuriadis told The Evening Standard. He then acquired all of Barry Manilow’s catalogue.

By January of this year, Mercuriadis made his deal with Young, while also hoovering up the likes of Lindsey Buckingham, Shakira, and the all-around industry heavyweight Jimmy Iovine. By March, Hipgnosis had 60,000 songs in its catalogue, 60 times the initial target, for which it had laid out $1.75 billion. That month, the company added the collected works of songwriter Carole Bayer Sager to a portfolio that had quintupled in less than a year. (The chart-clogging artists mentioned in the original prospectus have remained elusive.)

Neil Young sold a 50 percent stake in his 1,180-song catalogue to the upstart Hipgnosis Songs Fund for reportedly around $150 million.

“He’s done an incredible job of evangelizing music as an investment asset,” Olivier Chastan, a veteran music publisher, told me. The Church of England is among the investors who have bought into Mercuriadis’s bullish outlook on hooks and choruses. “Great songs are predictable and reliable in their income streams,” he told Barron’s, specifically “evergreen songs from award-winning songwriters”—the music-industry equivalent of blue-chip stock. In other words, sure things. It’s a model that is far more risk-averse than traditional music publishing, in which a Sony Music Publishing or Universal or Warner Chappell makes a bet on an unproven young songwriter. Hipgnosis has made its already rich investors richer by aggressively monetizing the catalogues it acquires: using advances in technology to track and collect royalties that might otherwise slip between the cracks, and finding licensing opportunities in film, TV, and the ever expanding realm of social media. As an example, Hipgnosis took one of its sure things, “Green Onions,” by Booker T. & the M.G.’s—the greatest instrumental hit of all time—along with a few other titles from the catalogue of the band’s late drummer, Al Jackson Jr., and, instead of passively collecting royalties, marketed the song hither and yon, thereby cranking the catalogue’s annual revenue by 50 percent, from $400,000 to $600,000.

A Bird in the Hand

“The traditional music publishing model,” Mercuriadis told The New York Times, “is something that I want to destroy.” He may be succeeding, at least when it comes to so-called legacy artists. What is the motivation for surrendering one’s life’s work? As the music journalist Jeff Slate noted in a recent NBC News blog post, Paul Simon “is making a rational calculation. He’s cashing out while he can.” For artists with enduring recognition and dwindling relevance, it’s a no-brainer: Take the money and run, as Steve Miller put it. (Miller still owns his song catalogue. Any takers?) Bill Flanagan, the author and former MTV executive who is now a Sirius XM Radio host, says, “For artists like that, it’s simply a matter of taking a bird in the hand. It’s a bit like someone watching the value of their home go up for 40 years and then at age 75 selling it and moving to a condo in Florida.” Les Watkins, a veteran Los Angeles–based music lawyer, concurs. “They do always say, ‘Keep your publishing’—and if you’re successful, it’s a long-term, predictable revenue stream. But when it’s not going to grow anymore, that’s when you sell: it’s just about getting paid faster.”

“It’s a bit like someone watching the value of their home go up for 40 years and then at age 75 selling it and moving to a condo in Florida.”

Ten years ago, if you were a legacy artist, getting paid for your catalogue meant a price that was maybe 10 times your annual earnings. In 2020, that multiple had risen to 17.5. Hipgnosis has been known to go to 22, depending on the catalogue. “You can never pay too much, because the life of hit songs is forever,” said Nile Rodgers, the Chic co-founder, songwriter, and producer, who sits on the Hipgnosis advisory board, in The New York Times. David Lowery, the leader of the alt-rock bands Camper Van Beethoven and Cracker, told me, “They are actually buying songs, in my opinion, too cheap.” At least some of them: “When certain songs get into the cultural fabric,” he said, “the revenue stream is quite stable.” The right song, or catalogue, in other words, can be an enviably lucrative long-term investment, especially when you consider how low current interest rates are.

Lowery, who trained as a quantitative analyst, has taught the business of music at the University of Georgia for the past decade. He has emerged as a leading critic of the streaming era, thanks, in part, to his viral 2013 blog post, “My Song Got Played on Pandora 1 Million Times and All I Got Was $16.89, Less than What I Make from a Single T-Shirt Sale!” (The song in question is Cracker’s 1993 hit, “Low.”) That headline is still used as shorthand for the economics of streaming, which, as has been widely noted, saved the music industry while driving down artists’ income. (Radiohead’s Thom Yorke famously referred to Spotify as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse.”) Paying a minuscule royalty rate, streaming has hobbled the ability of many musicians to make it on recorded-music sales. Add a coronavirus pandemic that has shut down live performance for over a year and it’s been pretty rough out there: a middle class of music creators—who may not be Dua Lipa or Bruce Springsteen but have solid followings—has taken it on the chin in a winner-take-all digital landscape.

It’s the reason David Crosby sold his publishing to Azoff’s Iconic Artists Group in March, following the Beach Boys sale. The acquisition solidified the perception, correct or not, of Azoff’s firm as the boutique for high-end artists from a Californian golden age (Iconic Artists also bought Linda Ronstadt’s recorded-music assets), while bringing Crosby, now 79, something that has eluded him throughout an illustrious career: financial security. “I don’t have savings and I don’t have any retirement program,” Crosby explained to The New York Times. “But I did have my publishing. It’s the only option that’s open to me to take care of myself and my family.”

Chastan, who helped engineer the Crosby deal with Iconic Artists Group, is optimistic that proactive management, and a big boost from emerging technologies, can keep legacy artists such as Crosby relevant for decades to come. “Look at Louis Vuitton,” he said, citing the fashion brand that was founded in 1854. “They’ve done it. Why can’t I keep Joni Mitchell relevant and maintain a fan base for her for a hundred years?” In the future, he said, it’s possible that our A.I.-immersed children and grandchildren could book Mitchell for a virtual house concert.

An Eternal Wellspring of Prestige

Mercuriadis and his ilk have emerged as something like Robin Hood figures for songwriters. Or at least as kinder, gentler versions of Mephistopheles: in exchange for your life’s work, they’ll exploit a grubby, exploitative business on your behalf and give you a better piece of the action.

Thanks to them, at least in part, the old business of buying and selling songs has arguably become more cutthroat than ever, with even the traditional publishers jumping aboard what is perceived to be an unstoppable locomotive. When Dylan sold his catalogue to Universal, considered the largest-ever acquisition of an artist’s publishing rights, the mood at Sony, Dylan’s longtime home, was one of utter dismay. As one Sony insider told me, it was as if Microsoft had bought Apple, or KFC had executed a hostile takeover of Popeye’s—demoralizing in the extreme. Dylan first signed to Columbia, Sony’s flagship record label, in 1961; the Dylan oeuvre was seen as foundational to Sony’s identity, an eternal wellspring of prestige. The loss stung. But there was business to attend to. “They hustled to secure Paul Simon just after that,” the Sony insider said. Dylan’s departure was said to have put Simon in a very good negotiating position.

“I don’t have savings and I don’t have any retirement program,” David Crosby explained. “But I did have my publishing.”

Maybe Mercuriadis and Azoff know something nobody else does about monetizing catalogues, generating excitement among artists, and wooing investors. Or maybe the recipe to their secret sauce is a combination of self-promotion, longtime relationships, making it up as they go, and unprecedented opportunities in a fast-changing music industry. The putative idea behind it all is that song catalogues, having proved their worth with decades of airplay, sales, and licensing, will continue along their money-minting trajectories for decades to come. Yet the unanswerable question is: Will they?

What kind of market share will, say, Simon or Crosby or Lindsey Buckingham have in 20 years, let alone 50, in a world where the refrain at the major labels is “Rock Is Dead”? (In case you’re wondering, that is a quote from the head of a Big Three music company.) Getting big quick, in the manner of Hipgnosis, means firing it all up now, getting investors to jump aboard a fast-moving train before it leaves the station. And where that train is heading, no one can really predict. Maybe in 20 years it will be Jay-Z making Dylan-size sell-offs. “We’re not going to see it stop anytime soon,” Chastan said. “The amount of capital in the marketplace is just staggering right now.”

For now, the publishing-acquisition train keeps a-rolling all night long. By the way, that song, the much-covered “Train Kept a Rollin’,” doesn’t look to be for sale at the moment. But who knows? It could be yours for the right price.

Mark Rozzo is an Editor at Large for AIR MAIL