When Charley Hill was 12 years old, his mother took him and his sisters to all the art galleries she could. One hot summer day when they were visiting the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, with another gallery visit planned, he started screaming about wanting to go for a swim instead. “My sisters backed me, obnoxious air-force brat that I was, and we went swimming,” Charley told me.

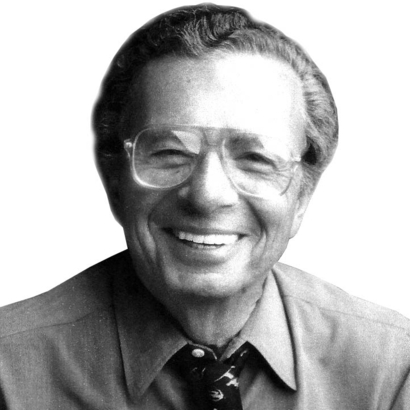

That swim notwithstanding, the obnoxious air-force brat never stopped going to galleries and became one of the world’s greatest art detectives. He helped to recover stolen artworks worth hundreds of millions of dollars, and could also discuss Van Gogh and Vuillard, as well as the use of light and shadow in Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Turner.

Charley died suddenly on February 20 at the age of 73. As one writer put it, “No force in the world of art crime exactly equals Hill.”

En Garde!

I first met Charley when I was editor and publisher of ARTnews and we developed a friendship that lasted more than 40 years. He once said that art crime is “serious farce,” because art is “irreplaceable but the farce develops when you’re fencing with crooks.” Charley fenced with crooks for about 45 years.

It started when he joined Scotland Yard and became a member of its fabled art-and-antiques squad, and continued 20 years later when he became a much sought-after private investigator based in London.

But Charley was no James Bond. He frowned on all kinds of gadgets. He never carried a gun—not even when he infiltrated gangs. “You survive by your wits,” he told Edward Dolnick, author of a 2005 book about Charley called The Rescue Artist. “Hardware will only let you down. Going unarmed doesn’t put me in extra danger. It puts me in less danger, because carrying a gun gives you a false sense of security.” In his professional work, Charley often played a swaggering American with a loud mouth and a thick wallet.

Charley came to know Mafia mobsters, members of Irish gangs, and the Balkan Bandits, who, he told me, “are various groups of Serbs, Croats, Kosovo Albanians, Macedonians, and Montenegrins who insist that you drink with them. Their two main drinks are apricot brandy and plum brandy,” he said. “They distill about 35 pounds of plum into a small bottle that is pure alcohol. They call it ‘rakia.’ It took me four days to get over the trip.”

Charley once said that art crime is “serious farce,” because art is “irreplaceable but the farce develops when you’re fencing with crooks.”

Charley, posing as the European agent of the Getty Museum, was one of two undercover officers who recovered Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, which had been stolen from Oslo’s National Museum in 1994. Despite missteps by local investigators, where the bad guys almost got away in what has come to be known as “the Sting for The Scream,” he was able to succeed in recovering the iconic painting.

“We had a slight problem when we set up a meeting with the thieves at Oslo’s Plaza Hotel,” he said. “Scandinavian narcotics officers were holding their annual meeting there. The place was crawling with plainclothes cops who might have recognized me and given away my identity. I saw two Swedish police officers with whom I had met earlier and was able to avoid them, while also sending them a message that if they should notice me they should not acknowledge me.

“The surveillance teams—Norwegian cops who had been assigned to keep an eye on what my colleague and I were doing—were looking at me and these crooks, but I explained to the crooks that the surveillance teams were there to protect the officers at the convention.”

Sometimes, Charley once said, information about stolen paintings can be helpful to a criminal not involved in a theft. “It happened after another version of The Scream and another Munch painting were stolen from the Munch Museum, in Oslo, in 2004,” he said. The police solved the case through a man who had been convicted of armed robbery.

M&M’s had announced, after launching their “newest masterpiece”—dark-chocolate M&M’s—that they were offering two million dark-chocolate M&M’s for the return of The Scream. “After the thief was convicted of his other crimes and sentenced to 20 years, his lawyer said to the cops that in return for conjugal rights with his girlfriend and the published reward of two million M&M candies, he’d arrange to have the pictures returned. The paintings were later recovered,” and the thief bartered his way to a better life in prison.

However, the M&M’s never made it to Norway. The Oslo police decided that a check for $26,000—the value of the candy—should go to the Munch Museum instead. As to conjugal rights, Oslo’s assistant chief of police would say only: “We have no comment on that.”

Charley’s other recoveries included, in 1993, a Vermeer, a Goya, and other paintings stolen from a home in Ireland. In 1996 he assisted German and Czech police in the recovery of many paintings stolen in Moravia and Bohemia, including a Cranach. In 2002 he recovered a Titian stolen from a stately home in England, and in 2012 he returned 16th-century works of art stolen in Sicily from the Piazza Armerina Cathedral.

He was born in Cambridge, England, to an English mother and an American father, at the time the assistant military attaché at the United States Embassy in London and who was later transferred to the air force.

Charley was educated in England, Germany, and the United States until 1967, when he dropped out of college and became a paratrooper in the United States Army, serving in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969. He graduated with a degree in history from George Washington University, and in 1971 won a Fulbright scholarship to Trinity College in Dublin. Later, he studied theology at King’s College in London before joining Scotland Yard.

He was personable, witty, and had a wicked sense of humor. There is a Yiddish word—“mensch”—that has nothing to do with success, wealth, fame, or status. Scholars say its key is character, decency, humanity, honesty, generosity of spirit. In other words, a good person. That was Charley Hill.

Charles Hill, art detective who helped recover The Scream, was born on May 22, 1947. He died on February 20, 2021, aged 73

Milton Esterow was the editor and publisher of ARTnews from 1972 to 2014. He currently contributes to The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair