For a certain group of readers, the name Daphne Merkin instantly brings to mind the spanking essay. Published 24 years ago in The New Yorker, “Unlikely Obsession” disclosed that next to Merkin’s dictionaries and thesauruses sat a treasured stock of books on sadomasochism; that she not only fantasized about spanking but had indulged her desire; and that she felt a mix of relief and shame, not unlike the experience of being spanked, in putting all this on paper. Writing in 2012, the journalist Virginia Heffernan recalled the literary public’s takeaway: “Something is wrong with Daphne Merkin.”

Today, many readers would not view Merkin’s confessions as particularly scandalous or subversive. Her politics are another matter. In 2018, Merkin wrote a New York Times op-ed suggesting that many women, “including many longstanding feminists,” are publicly joining in on the #MeToo chorus, but privately “rolling [their] eyes, having had it with the reflexive and unnuanced sense of outrage that has accompanied this cause from its inception.” (More recently, Merkin has expressed skepticism about cancel culture, or the “shunting aside of every public figure who does not maintain a spotless private life.”) The Cut issued a reply, headlined, “Daphne Merkin widens the Feminist Generation Gap.”

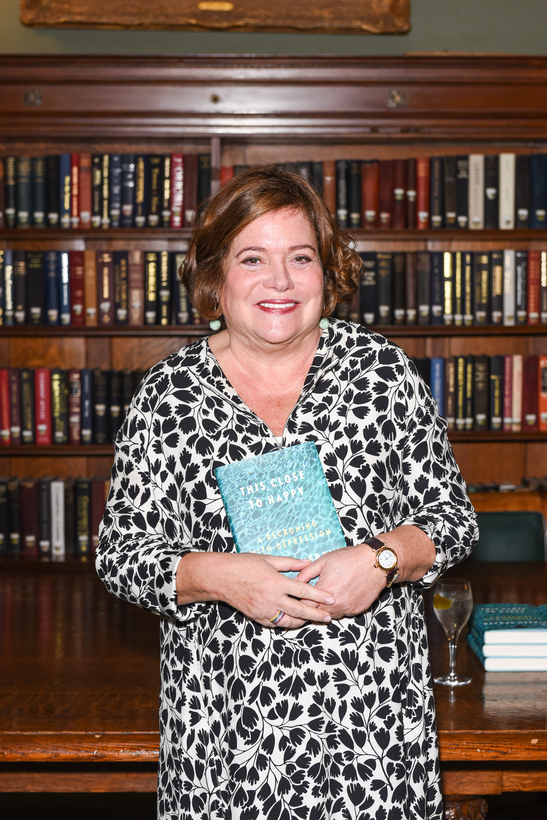

“One difference between your generation and mine is I actually like the word ‘cunt,’” Merkin recently told me. We were discussing her latest novel, 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love, which Merkin began writing three decades ago. The book revisits the subjects explored in the spanking essay—“erotic obsession and sexual submission,” as Merkin described it in The Washington Post.

Spanking 2.0

The protagonist in Merkin’s new novel is Judith Stone, a 29-year-old book editor, as Merkin once was, who was raised, like Merkin, Jewish. The romantic anti-hero is Howard Rose, a brutish and shrewd criminal defense lawyer for whom Judith falls deep into a waiting-by-the-phone, non-stop-daydreaming delirium. Interspersed throughout are five short “Digressions,” in which the third-person narration switches to first-person. This narrator (never identified but almost certainly Judith) ruminates on the challenges of writing, the ideal reader, and her literary inspirations. Mirroring Howard’s manipulation of Judith, she is at once inviting, wanting “you with me, figuring out this story along with me,” and rejecting—“perhaps you are not the reader I want after all.”

An earlier version of this book was called The Discovery of Sex. Before Judith meets Howard, she has hardly masturbated and never orgasmed. She doesn’t submit to Howard so much as to her own desire, which she finds debasing in and of itself. Judith’s inhibitions stem in part from her personality—sexual sincerity doesn’t couple with a natural inclination toward irony—as well as her chaste and conventional upbringing. “I don’t know how much that has changed in the world,” Merkin says. “I think we still have to come to terms with what female desire looks like.”

Younger readers may find Judith and Howard’s sex fairly vanilla—there are fingers in the expected places, a blowjob in the bathtub, some phone sex. There is no spanking here. Only at the end does the sex get a little out there, with Judith on all fours. “I considered not putting in the crawling,” she tells me. “Maybe this is, again, a generation gap.” An early reader, a friend of Merkin’s who is a writer “from the Ms. magazine period,” considered the sex too degrading to be relatable. “My editor at F.S.G. was worried it was much too S&M-y.”

Younger readers may find Judith and Howard’s sex fairly vanilla. There is no spanking here.

When Fifty Shades of Grey topped best-seller lists, Merkin says she was sent “at least six copies. . . . I called it consumerist sadomasochism, because I found most of the book was about his things—his plane, his suits.” But more recently, a handful of lauded young writers outside of mass-market erotica—notably, Sally Rooney (Normal People), Kristen Roupenian (author of the viral short story “Cat Person”), Lisa Halliday (Asymmetry)—have explored submission and domination in relation to broader gender dynamics. Merkin’s novel could be seen as part of this drift.

In both Rooney’s Normal People and Merkin’s novel the adult desire for erotic submission originates in childhood. “What I was trying to bring in is that the setup for these kinds of relationships is usually a background of deprivation or abuse,” Merkin tells me. In her opinion, the sadomasochism in her book is largely mental. It’s the push-and-pull of Howard’s alternating indifference and absorption that stimulates Judith’s longing. Howard echoes Judith’s parents, her mercurial mother and distant father, and acts as the parent she never had, one who is fixated on her and gives her permission to enjoy sex. “And that’s a big permission,” Merkin says.

Rooney’s protagonist, Marianne, is likewise given permission to enjoy sex, but only at the end, and it’s of a certain kind: sex without violence. She learns to temper her inclination towards self-destruction while still getting off on compliance thus salving psychic pain in sexual pleasure. In the world of Merkin’s novel, and in Merkin’s view, a resolution like Marianne’s is not possible. “I couldn’t find a way to rescue my self-destructive protagonist from her dilemma,” she wrote in The Washington Post, “except through some kind of melodramatic device” such as the Anna Karenina option of suicide; the Story of O option of enslavement; and the Nine and a Half Weeks option of insanity. “Was this kind of deus ex machina inevitable?”

Laws of Survival

Merkin’s struggle to spare Judith was not simply a matter of narrative convention. What she detects in these works is a kind of psychological credibility: Judith’s literary predecessors were compelled by their psyches toward tragedy. “You have to go up against your own instincts,” Merkin says of her escape from a sadomasochistic dynamic. Judith’s instinctual attraction to submission and debasement signals a dark and deep-rooted impulse towards self-annihilation that, Merkin suggests, should not be accommodated. It is the conscious manifestation of an even darker, unconscious desire to die, a Freudian idea with which Merkin agrees.”You could end up dead, or you could just end up mangled psychologically,” Merkin says of such relationships. Where Rooney’s novel offers the possibility of healing, Merkin’s novel suggests that scratching the itch will only open old wounds.

“When I first described what I wanted to write about 30 years ago,” she says, “it was, ‘Can you be in such a relationship, presuming it’s not good for you on some essential level?’” Judith can’t square her feminism with her fixation on a man whom she considers to be a misogynist. It is only when Howard suggests a threesome, a request that is mismatched with her own need for his undivided attention in the bedroom, that Judith is able to walk away. Even then, she finds herself in the grip of obsession, outside Howard’s apartment in a phone booth, begging him to see her. “Aren’t you supposed to be on a ledge right around now?” Howard asks her.

“What fascinates me,” Merkin says, “is how far can people go off the track of ‘conventional’ romantic lives—whatever that means—how far can they go off the track and survive.”

“You have to go up against your own instincts,” Merkin told me about her own experience of escaping a sadomasochistic dynamic.

The novel opens with our protagonist married and pregnant, recalling this period of her life from behind the safe walls of domesticity. She is mostly happily married, but can’t shake the memories of Howard, which return in waves, the residue of obsession. “How well does passion go with domesticated life? Can you keep up a certain level of sexual excitement when you’re sharing a bathroom and toothpaste?” Merkin asks. “It was Freud’s question, certainly. To me, it’s an almost unresolved question. In some ways maybe other centuries had it better. They never attributed so much passion to marriage.” (Merkin’s only marriage ended after nearly a decade, in 1995.)

Merkin went to Barnard College in 1972, just after the “first excited yelp of feminism,” as she describes it. She recalls involving herself in feminism to “a certain degree,” but, she says, her “nature is incredibly non-group-joining.” A friend recently called her a “feminist of one,” which strikes Merkin as fitting.

In spring of 2019, while teaching a creative writing course at Columbia called The Language of Eros, Merkin learned that “the new foreplay is choking. Everybody was writing about it,” she says. “But it seemed much less conscious. It’s gone along with.” Barnard now has a student-run sexual wellness group called AllSex, which hands out checklists for students to go over with their partners: are you interested in anal play? Age play? Tickling? Giving? Receiving?

Self-Objectification

To Merkin, these are “strangely unpsychological times,” an era of “fleeing from ambiguity.” She doesn’t buy that a woman can engage in B.D.S.M. and feel no sense of misalignment with feminism. “I think one of the things your generation has done, for better and worse, has taken objectification into their own hands and sort of self-objectified,” she says. What feminism needs, in Merkin’s view, is some Freud, or at least, some “psychological awareness.”

She isn’t referring to the kind of psychological thought that has been successfully mainstreamed by #MeToo and its attendant focus on trauma—today, the notion that past abuse explains present behaviors or patterns is ubiquitous. But such an understanding, Merkin thinks, is just the first in a series of steps. When it comes to B.D.S.M., she argues that it would be a mistake to go on accepting the pleasures of pain simply because the foundations of that desire are understood. Pleasure fades, but pain persists. Sadomasochism, she suggests, is better explored on the analyst’s couch than in the bedroom.

What feminism needs is some Freud, or at least, some “psychological awareness.”

Interiority, Merkin tells me, “has been thrown to the wayside in favor of an externalized expression—pink pussy hats and such—of what feminism is about.” To be sure, mining the past has limitations, and Merkin mostly identifies these in Freud’s unconscious: We will always remain mysteries to ourselves. Even Judith, who is hyper-psychological in her thinking, does not, for instance, make the connection between the death of her therapist and her attraction to Howard.

Merkin thinks contemporary feminism is leaving out part of the story, and so is much contemporary fiction. She sees a danger in flattening individual experiences into a master narrative, or looking at the past only to imprint it with a present perspective. “If all of fiction were about validating or confirming what you already feel as either a woman or feminist,” she says, “it wouldn’t be worth the reading.”

Clementine Ford is an Associate Editor at AIR MAIL