In the new world, there will be no more Henry Chinaskis. It will be impossible. Chinaski, a fictional creation in the image of his maker, Charles “Hank” Bukowski, lived on the sacred grime and grit at the edges of daily life. He wanted the truth, without compromise and without veil. He knew that as a writer, his responsibility was to capture life exactly as he found it: beautiful and hideous, and often both at once.

Sunday is Bukowski’s 100th birthday. Though the writer died in 1994, his sinuous body of work (some 60 books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction) remains an essential testament to the unsung depths and corners of American life. The passage of time has not diminished the power of his prose; his works have been translated into 12 languages and have inspired five major motion pictures. Bukowski’s singular style and ethos preserve their vitality because unlike other poets, he was not cloistered in an ivory tower, postulating on the abstract nature of the human heart.

He wanted to be as close to the stinking mess as a man could be.

Days at the Races

In Bukowski’s time, there were still beloved haunts one could frequent: the dive bar, the small café, the racetrack. These places were breathing organisms, Petri dishes of human life. From his courtyard bungalow on De Longpre Avenue in Hollywood, Bukowski would go to the track at Santa Anita every week like a religious practice. Though his ferocious intelligence and exacting gaze went everywhere with him, in such surroundings Bukowski was simply among his peers: the wounded and the hopeful. Elbow to elbow at the rail and the bar, Bukowski observed the gamblers and drinkers in their triumphs and tragedies, and basked in the rhythm of their language.

The racetrack served as a microcosm of reality for Bukowski, in which he saw the glory and the devastation of existence manifested in a spectatorial sport. In a poem titled “no. 6”, Bukowski describes the scene:

the horses at peace with

each other

before the drunken war

and I am under the grandstand

feeling for

cigarettes

settling for coffee,

then the horses walk by

taking their little men

away—

it is funereal and graceful

and glad

like the opening

of flowers.

This spectacle was sacred and profane, like the last smoke in a pack of cigarettes. Hank didn’t smoke because it was good for him. He smoked because it hurt. Life hurt all over. But a little pain made the day to day, and the moment-to-moment, a little easier to fathom. Every drag of a cigarette is a little like greeting death; an exhalation of cigarette smoke is like asking death to take a seat. In his life and in his writing, Bukowski was a death tamer. To bet on a horse in a race is to relive the deepest thrill and risk of life: a physical chance taken with the odds. For him, a day at the track was a symbolic philosophy, depicted in a battle of nine races. “He’s losing, losing, losing, but he keeps trying. And at the end, he finally bets. And he goes, ‘There you go my friends. Loser for eight races, winner in the ninth.’”

He wanted to be as close to the stinking mess as a man could be.

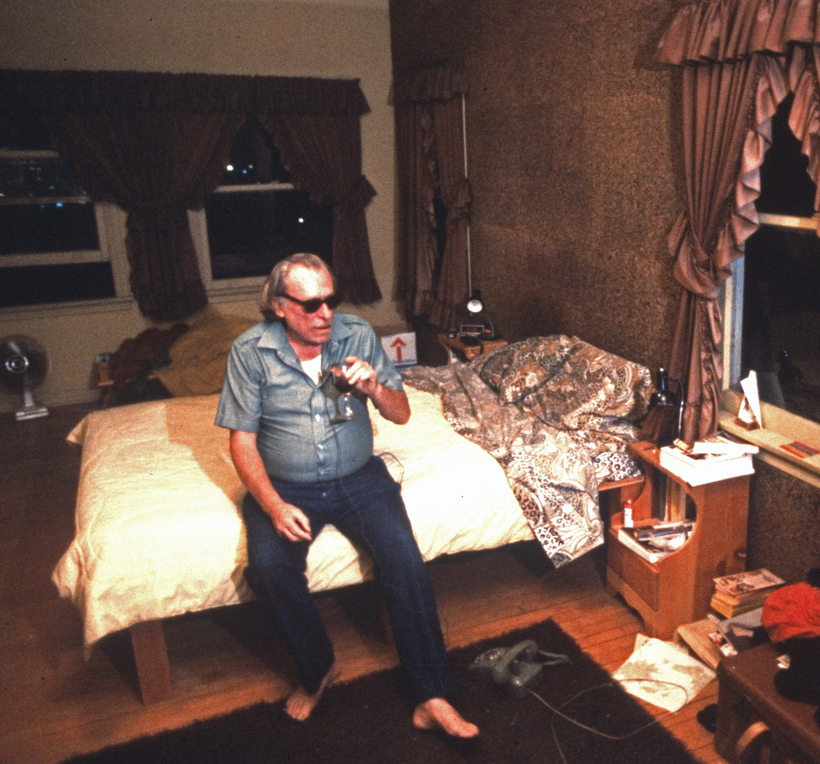

I spoke with director Taylor Hackford, who is as much an admirer of Bukowski the writer as he was a close personal friend of Hank the man. Hackford’s wife Helen Mirren was also a friend of Hank’s, and counts herself among his devoted readers. Hackford is the director and producer of the 1973 documentary Bukowski, in which he traveled to San Francisco with Bukowski for his first large public reading, sponsored by the independent beacon of counter-culture City Lights Bookstore. Over the course of their friendship, Hackford observed the complex duality of the man and the literary persona he came to symbolize. “Because Hank chose to write working class,” Hackford says, “because he talked about the rough-and-tumble world, the shitty jobs that he had so that he could survive, because he went to bars and there were brawls—everyone thinks a certain way about Bukowski. They wanted to see the dancing bear but you know, it’s just not true. The man was much more sensitive than that.”

There was a time when on any given night, Hank could have walked into his favorite local bar, the familiar tattered walls reeking of human ecstasy and chaos from a million nights before. He could have sat down on a cracked vinyl stool, felt the sticky pink gum under the smooth bar as he slid in. In the eyes of a stranger across the room, he would have believed he could still find her, the forever one, elusive as Dante’s Beatrice. He would recognize her, though she may call herself by another name—Joan, or Amber, or Barbara, or, finally, Linda. These women were more than muses; in many ways they were Hank’s greatest teachers, and he studied the rituals of intimacy with complete fascination. To love, one must be hopeful. To write about love, one must be cynical.

Hackford remembers, “He couldn’t—because he really considered himself to be ugly—he couldn’t come on to women, he couldn’t have a conversation with a woman. ‘I can’t do that,’ he said, ‘but what I can do, is I can write them letters. I can write them and in my words, I seduce them long before we’ve ever met face to face, because I know when they meet me face to face, they’re gonna have a reaction to this face.’” As a teenager, Bukowski survived a brutal upbringing at the hands of a physically and emotionally abusive father, and suffered adolescent acne that left him permanently scarred. “The nature of Bukowski as an outsider was manifested on him in a physical way long before,” Hackford says. “He wasn’t a bad looking guy, you know, but the fact is that with all those pocks, he did think of himself as kind of a monster and therefore he retreated inside [himself].” But in the dark neon glow of a dive, Bukowski’s heart would beat in his chest: one more time, one more chance to fall in love. Maybe this time, it would be the right fix—the shot of liquor that would finally quiet the roaring ache, or the right lover that would finally understand.

To write about love, one must be cynical.

As I write, it is practically impossible to meet anyone at a bar. At Santa Anita, horses race for empty stands. The floor is empty, ghostly and resonant, with the echoes of fortunes won and lost. The restaurants, bars, and meeting spaces that remain open will be scrubbed and cleaned from top to bottom. A fresh coat of paint on the walls, tables set far apart by gloved hands. In the interest of health and hygiene, no one can deny the necessity of decontaminating common areas. But what will be erased will be lost forever. A way of being, traces of memory and time. Faded photos of former lovers pinned to the wall alongside creased winning tickets from opening day; a lipstick kiss left anonymously on a bathroom mirror. Bukowski wrote to capture these fragments of living history. And now it is vanishing.

To read his work is to feel Bukowski could live anywhere, survive any conditions, like a relentless flower coming up through the cracks in the concrete. But it’s hard to imagine Bukowski using hand sanitizer.

Greer Sinclair is a writer based in Los Angeles