“The Queen wore no crown, no robes of state, but it was the Queen in flesh and blood. I saw her. I heard her deep, low voice saying, ‘Tell them we are delighted with their songs.’ I wondered why the Queen did not speak these words to us. We were within hearing.”

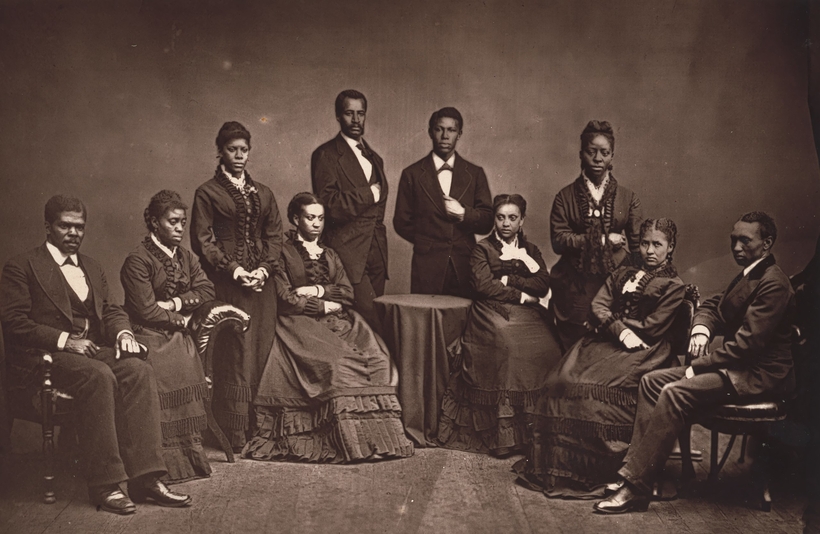

So wrote Maggie Porter, one of nine student choristers billed as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who in the wake of Emancipation brought their heritage of spirituals to the nation, the world, and the 50-something Queen Victoria in the fourth decade of her 63-year reign. Seven of them had themselves been enslaved. The documentary Jubilee Singers: Sacrifice and Glory, produced and directed a quarter century ago for the PBS series American Experience by Llewellyn Smith, balances deserved celebration against an unblinking view of many hardships. The film is as gripping today as when it first aired, on May 1, 2000.

The Jubilees’ odyssey began in 1871 on the initiative of George Leonard White, a white Gettysburg veteran and impassioned musician then serving as treasurer of the newly established Fisk School, in Nashville. Founded for the education and advancement of freed slaves, many of them illiterate, Fisk (today a university) was teetering on the brink of ruin when White took his most talented singers on the road in a desperate effort to raise funds.

At first, audiences gave their programs of popular favorites a frosty reception. But when the students introduced their unknown “cabin songs,” “plantation melodies,” folk hymns, and “jubilees” from the Antebellum Era, they struck a chord. In modes from mournful to exuberant, the unadorned, purposefully repetitive tunes and lyrics struck home with disarming force.

“I don’t know when anything has so moved me,” that notorious sentimentalist Mark Twain confessed. And when the Waltz King Joseph Strauss II heard the ensemble in Boston at the World’s Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival, which marked the end of the Franco-Prussian War, he threw his hat in the air in his excitement.

A British tour, and the private performance for the Queen, followed soon after. Where once the Jubilees were lucky to cover their shoestring travel expenses, they eventually went on to return tens of thousands of dollars to their alma mater, funding the construction of Fisk’s monumental Jubilee Hall. But their punishing schedule took a heavy toll on the singers’ health and well-being. For some, along the way, international stardom seems to have devolved into its own form of indentured servitude.

By and large, songs of the South are battlegrounds now. Be it a Stephen Foster parlor ballad, Uncle Remus’s “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” from Walt Disney’s now-contraband Song of the South, or Robbie Robertson’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” … self-appointed grand inquisitors step up to sniff out white supremacist heresies.

Spirituals stand apart. In origin and intent, they are the very opposite of art songs, requiring neither special training nor an exceptional voice to sing them. Yet from the trail-blazing Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson of yesteryear to Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle, and now Davóne Tines and Julia Bullock, all great Black classical vocalists have reserved a special place for spirituals in their hearts and on their recital programs. Though the Fisk Jubilee Singers possessed next to nothing in a material sense, the light they lit shines on.

Jubilee Singers: Sacrifice and Glory is available for streaming on YouTube

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii