Sixty-one years ago, Francisco de Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington was stolen from the National Gallery. It was the first theft of an artwork from that institution in its 137-year history, and one of the most audacious art heists of the 20th century.

The assumption was that some sophisticated crime syndicate had stolen the painting. Four years later, a 61-year-old unemployed taxi driver from Newcastle claimed to have taken it – as a bargaining chip for his quixotic campaign to secure free television licenses for pensioners. Kempton Bunton was tried, but acquitted on the grounds that he had only “borrowed” the Old Master.

This improbable tale is the subject of The Duke, a delightful film starring Helen Mirren and Jim Broadbent. But just as the film contains a further surprising twist so too does the real story. It was Bunton’s son, John, known as Jackie, who stole the painting, not his father, and today Jackie’s son, Chris (Kempton’s grandson), is describing to me exactly how his father pulled off the astounding feat.

When I ask directly if his father was the thief, Chris Bunton replies, “There’s no doubt he was. He was 20 years old at the time, and Kempton was not involved in the planning of this in any way, shape or form. He got involved after the fact.”

He says his father has written a brief confession to Chris’s own son, Jay, which states, “Dear Jay, this is your grandfather. I am fully responsible for taking the Goya. My father had no involvement in it at all until after the fact.”

Jackie “was not proud” of taking the painting, Chris adds. “He actually said it was the dumbest, stupidest thing he ever did.”

As for Jackie, he is now 80, widowed, ailing and largely confined to his flat in North Shields. Door-stepped by a reporter, he refused to discuss the infamous theft. “Those things are best left in the past,” he said. “I don’t talk about what happened then.”

Goya painted the Iron Duke, resplendent in a bemedaled red tunic, on a 25 x 21in mahogany board following his victory over the French at Salamanca in 1812. In 1961 an American art collector, Charles Wrightsman, bought The Duke of Wellington at Sotheby’s for $391,000, but the prospect of the portrait of one of Britain’s most famous soldiers leaving the country caused uproar. It was saved for the nation with a $363,000 gift from philanthropist Isaac Wolfson and $111,000 from the Treasury.

On August 3 that year, it went on display at the top of the National Gallery’s central stairs, uninsured and protected only by a rope barrier. Seventeen days later, before Wolfson had even sent his check, it vanished.

The theft was a sensation. Ports and airports were closed. Trains were searched. Interpol was alerted. The gallery offered a $18,000 reward. The police even took postcards of the portrait from the gift shop for identification purposes. But they found no clues except some mud on the windowsill of an upper-floor Gents, a ladder to the courtyard below, and scuff marks on the gallery’s rear wooden gate.

A 61-year-old unemployed taxi driver from Newcastle claimed to have taken it.

More people went to see the empty space where the painting had been displayed than had gone to see the portrait itself. “How do you feel when you’ve lost a Goya? You feel a bloody fool,” said Sir Philip Hendry, the gallery’s director, who offered to resign.

There was rampant speculation about the identity of the mastermind behind the theft. Some noted recent art thefts on the Continent and believed a crooked millionaire was secretly amassing a private collection. Others drew a connection with the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian patriot, 50 years earlier to the day.

But everyone agreed that the theft itself was the work of a consummate professional. Lord Robbins, chair of the gallery’s trustees, declared that the thief must have been “slim and physically fit, and the cunning with which he carried out the raid suggests that he was probably a commando or something like that. A man without fear.”

Nine days after the painting vanished, Reuters news agency received a note written in pencil and crude capital letters. “Query not that I have the Goya,” the writer began, before proceeding to describe a label on the back of the painting. “The act is an attempt to pick the pockets of those who love art more than charity,” the note continued. “The picture is not, and will not be for sale… It is for ransom – £140,000 [$391,000] – to be given for charity.” The authorities ruled out any such deal.

Eleven months later, another note was sent to London’s Exchange Telegraph news agency.

“The Duke is safe. His temperature cared for – his future uncertain,” it declared. “We ask that some nonconformist type of person with the sportitude of Butlin [Billy, founder of the holiday camps] and the fearless fortitude of [Field Marshal] Montgomery start the fund for £140,000… Propriety may frown – but God must smile.”

The authorities again rejected the offer, and, as the mystery deepened, Dr. No, the first James Bond film, was released. In one scene Sean Connery walks through the villainous Julius No’s underground lair in Crab Key, Jamaica, and spots Goya’s portrait on an easel.

The next note was sent to the Exchange Telegraph 17 months later, in December 1963. Scotland Yard “are looking for a needle in a haystack, but they haven’t a clue where the haystack is”, it stated before making an offer to Britain’s press barons.

“Here is my plan in brief – turn it down offhand, and I go to sleep for another year… I propose to be picked up hooded in a dark London side street with Goya. Your car to have 3 guards to safeguard me from interference from the photographers assembled at the gallery – I am not to be questioned. Press men will take pictures of the return of Goya, after which I am to be secreted out of the rear door, and driven to any London side street named.”

In return for those photographs, the writer proposed that each editor give five shillings per thousand readers to a charity of his choice. “Pinch penny editors who do not print to be sent to Coventry. Print and don’t pay editors, to be sent to Tristan [da Cunha].”

The note finished with an appeal to Lord Robbins. “Assert thyself and get the damn thing on view again… I am offering threepennyworth of old Spanish firewood, in exchange for £140,000 of human happiness.”

In March 1965 the Exchange Telegraph received a “final Com” beginning: “Goya’s Wellington is still safe. I have looked upon this affair as an adventurous prank – must the authoritys [sic] refuse to see it this way? I know now that I am in the wrong, but I have gone too far to retreat. Liberty was risked in what I mistakenly thought was a magnificent gesture – all to no purpose so far.”

The writer then proposed to return the painting provided it was put on show for a month with a five-shilling viewing charge and the proceeds given to a charity of his choice. “The matter to end there – no prosecutions – no police inquiries.”

Kempton Bunton was tried, but acquitted on the grounds that he had only “borrowed” the Old Master.

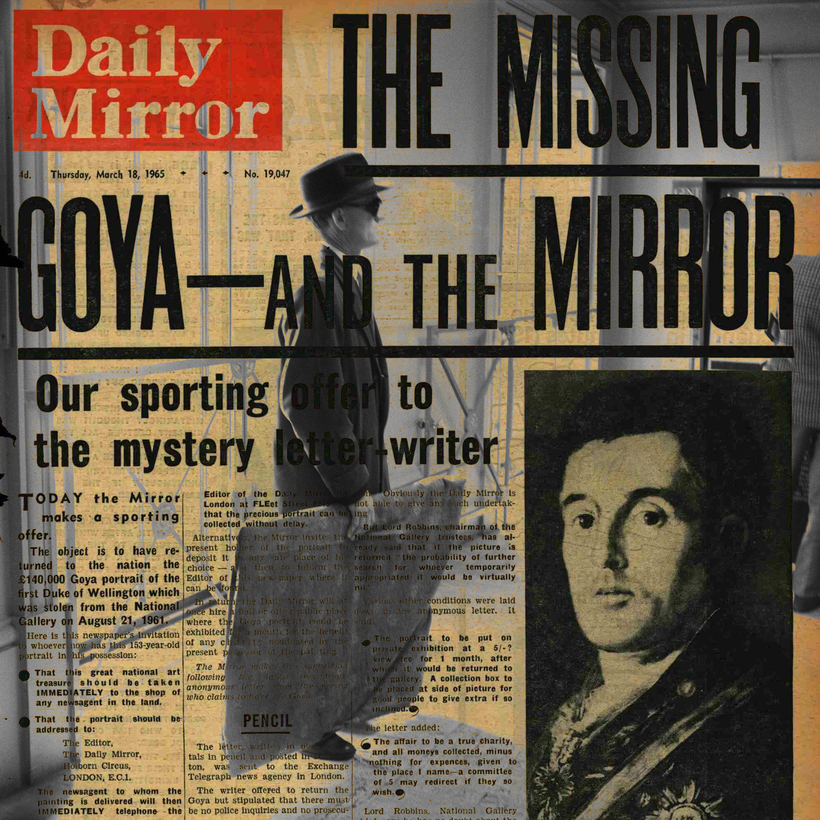

Hugh Cudlipp’s Daily Mirror responded by publishing a “sporting offer” on its front page. “This great national art treasure should be taken immediately to the shop of any newsagent in the land,” it said. In return, the Mirror would attempt to put it on display.

Two weeks later the editor received a left luggage ticket from Birmingham’s New Street station. There the police found the The Duke of Wellington, frameless but undamaged after his four-year kidnapping, wrapped in brown paper secured with a length of clothesline.

The Mirror crowed, but never staged the promised exhibition. In a final message the thief wrote: “We took the Goya in sporting endeavour – you Mr Editor pinched it back by a broken promise. You furthermore have the affrontary [sic] to pat yourself on the back in your triumph… I am a man of no substance – but my word I do not break.” He also sent a seven-shilling postal order to the left luggage office to cover the 17-day storage fee.

There the story would have ended had a man in a trilby and cheap NHS glasses not walked into Scotland Yard two months later. “My name is Kempton Bunton and I’m turning myself in for the Goya,” he declared. “You don’t have to look any further. I’m the man who took it.”

The police did not believe him. Tall, aging and weighing nearly 18 stone, Bunton was no cat burglar. But he provided samples of paper and handwriting that matched the ransom notes, and described how the painting had been packed for storage at the left luggage office.

Bunton also produced a written statement that said he was turning himself in because he was “sick and tired of the whole affair”, because his secret had leaked and he did not want “a certain gentleman” claiming the reward, and to “avoid the stigma of being brought here in chains”. He insisted he was guilty of “honest to goodness skulduggery”, not a criminal act, and declared, “I shall fight this case on the goodness of it.”

“Now make up your minds. Are you going to charge me or not?” he berated the police. They eventually did so because it also transpired that Bunton had a bizarre – but just about plausible – motive.

Kempton Bunton (named after his father had enjoyed a good day at the races) left school at 12 to help his mother run a pub while his father fought in the First World War. He married, had seven children, and scraped a living doing driving and menial laboring jobs, several of which he lost because he was argumentative. He was also a dreamer who believed in social justice and wrote numerous radio and television plays that were invariably rejected.

By 1960, Bunton had begun campaigning for free television licenses for pensioners, and was three times jailed for refusing to pay his $11 license fee (he claimed to have modified his set so it received only ITV, not the BBC). He had also discovered from his local library that Wellington was an autocrat who despised the lower classes, and reckoned that “his portrait might bring more happiness into the world than ever he had himself”. Had Bunton received the $391,000 ransom, he said, he would have used it to give licenses to lonely old folk.

His trial began at the Old Bailey in November 1965. He was represented – for fun – by Jeremy Hutchinson, a top criminal barrister whose other clients included the Soviet spy George Blake, the Great Train Robber Charlie Wilson and the Profumo scandal model Christine Keeler. The Duke of Wellington was produced in court as evidence.

Bunton, the quintessential English underdog, charmed the jury. He said he was disgusted that $391,000 could be spent on a painting when many old folk could not afford to watch television. Given his recent campaign, he had been unable to identify free licenses as the charity in his ransom notes “because that would have been like signing my signature to the taking of the picture”. He had stored the painting in a bedroom cupboard in his council house, but had not informed his wife “because the world would have knew [sic] if I’d told her”.

He never intended to keep the portrait, he insisted, because “it was no earthly good to me… I wouldn’t hang it in my own kitchen if it was my own picture.”

Bunton was, said Hutchinson, “rather a darling”, and the jury acquitted him of stealing the Goya thanks to a loophole in the 1916 Larceny Act that required proof a defendant intended “permanently” to deprive an owner of his property.

The judge was less amused than the jury by Bunton’s antics. “Creeping into public galleries to extract pictures of value in order to use them for your own purposes has got to be discouraged,” he declared. He sent Bunton to Wandsworth prison for three months for stealing the portrait’s long-discarded frame.

The government changed the law to make it an offense to remove items from public galleries, and ordered an inquiry into security at Britain’s galleries and museums. Lord Arran and Robert Pitman, a journalist, placed an advertisement in The Times announcing the foundation of the Kempton Bunton Society “in honour of a rare, if misguided eccentric who has exposed false art values and done little harm while giving much fun”.

That would have been the end of the matter, had the police not stopped a stolen van in Leeds four years after Kempton’s trial. The driver was his son, Jackie, who asked for another offense to be taken into consideration. He confessed it was he, not his father, who took the Goya. Sir Norman Skelhorn, the director of public prosecutions, chose not to charge Jackie provided he kept quiet. The authorities had tried the wrong man, says Chris, and his father’s confession was “a big embarrassment” for them. Thus Jackie managed to steal a masterpiece from the National Gallery and escape scot-free.

The police did not believe him. Tall, aging and weighing nearly 18 stone, Bunton was no cat burglar.

Chris Bunton was born shortly after Kempton died in 1976. His family never talked about the great skeleton in its cupboard while he was growing up. “A lot of them were really ashamed of the whole thing,” he says. Not, that is, until Jackie told him the story on a 30-hour ferry trip from Newcastle to Bergen when Chris was a teenager.

“I thought he had had one too many drinks,” Chris recalls. “Even then I still didn’t understand the scale of it all. It was a wacky thing to hear all of a sudden. That was the only time he really mentioned it.”

Chris left school, married an American student at Newcastle University, and moved to New York where he organizes online events for IT companies. After his father suffered a major heart attack in 2013, he decided to preserve the true story – not the fictionalized version in Kempton’s memoirs – for posterity. He took another ferry trip with his father, this time to Amsterdam, plied him with questions and recorded the answers.

Jackie told him how the gallery’s acquisition of the Goya was big news in August 1961. He was driving taxis in Newcastle at the time, and conceived the idea of stealing it either to make some money – he had heard insurance companies would pay 10 percent of a stolen painting’s value to get it back – or to support his father’s license fee campaign.

“It was just an idea at first. I never really believed I’d go through with it. I just took one step at a time and things just kept going in my favor, almost like God was helping,” he said.

He moved to London, rented a room off Tottenham Court Road, and found work delivering fur coats while he laid his plans. He picked up a map of the gallery from its front desk, and identified the Gents as his way in. He put tape on the door, a matchstick on the window and a bit of fluff on the painting to check they were not locked or removed at night. From an indiscreet guard he learned that the gallery was patrolled every 20 minutes at night, and that its alarms were switched off early each morning for the cleaners. He scoped out the back of the gallery from the second floor of a nearby library, and noticed that builders were working on it. He was all set.

On the night of August 20 he dressed in crepe-soled shoes and an old commissioner’s coat purchased from a charity shop. He stole a Wolseley car from a yard in Old Street – “He was a bit of a petty criminal at that point,” Chris admits. At about 4am on the 21st, he parked behind the gallery and scaled the wall by standing on a parking meter.

He then walked through two inner courtyards, took the builders’ ladder and climbed through the window of the Gents. “I kept as low as I could through the gallery,” he said. “I didn’t bump into any guards and there were no alarms. At the picture I placed one foot inside the rope barrier, quickly grabbed the painting, and without wasting any time, left the way I went in.”

He jump-started his stolen car. As he drove off with the painting in full view on the back seat he was reprimanded by a policeman for going the wrong way down a one-way street. Back at his digs he removed the frame with a hacksaw and hid the painting under his bed.

After that he did not know what to do because, “I’d never expected to get as far.” So he telephoned his father. “I still remember the conversation,” Jackie said. “I told him I had a painting and he said, ‘Is it the Goya?’ He guessed as it was all over the news.”

Kempton came straight to London and sent Jackie home. He waited two weeks for the hullabaloo to pass, then took a train back to Newcastle with the painting. There he wallpapered it behind some hardboard in a built-in cupboard.

Jackie said Kempton began sending ransom notes “to defuse the situation and soften the blow in case I was caught. The charity demand was intended to show we weren’t out for personal gain.” Thus “the painting inadvertently became the biggest tool [Kempton] ever had for his campaign”. Jackie’s only other role was to take the painting to the Birmingham left luggage office four years later.

Asked why Kempton subsequently confessed to a crime he had never committed, Jackie explained that his brother Ken’s girlfriend, Pam Smith, had learned of the theft and was threatening to turn him in.

He did not step forward when Kempton went on trial because, “He ordered me not to. He didn’t want me to get into trouble, and I think he enjoyed the whole adventure and the publicity he was winning for his campaign.”

Jackie finally confessed in 1969 because, he said, “I just wanted to get on with my life and was tired of having it hanging over me. I didn’t want it to come up down the line and wanted it removed from my father’s record as he couldn’t get work.” The authorities did not prosecute Jackie, he said, because “they didn’t want the hassle and further embarrassment”.

Thereafter Jackie “pretty much turned his life around”, says Chris. He married, had children and ran his own one-man removal business until he retired.

In 2014, Chris turned the whole extraordinary, long-forgotten story into a screenplay and offered it to Nicky Bentham, a British producer, who was enthralled. “It’s just an incredible tale and uplifting story… There’s so much delicious material,” she says.

Bentham then offered a revamped screenplay to Roger Michell, the film director of Notting Hill fame, who was equally enchanted. “The script read like a great Ealing comedy from the Sixties,” Michell said before his death last September.

The film’s UK premiere will be held where the story all began, at the National Gallery. Jackie will not be there but the duke himself will be, having recently returned from Japan and Australia as part of a touring exhibition entitled “Masterpieces from the National Gallery.” And Kempton Bunton will doubtless attend in spirit, smiling at the way things have turned out.

Over-75s were awarded free television licenses in 2000, so Kempton could be said to have won his campaign in the end. And after all those rejections of his radio and television scripts his ultimate screenplay – the story of his eccentric life – has now been turned into a funny, gentle and surprisingly touching film starring two of Britain’s foremost actors.

Martin Fletcher is a London-based freelance journalist specializing in foreign affairs and domestic politics. He is also the author of Almost Heaven: Travels Through the Backwoods of America