In her award-winning Tribes, the British playwright Nina Raine examined a dysfunctional Jewish family and the struggle to pass on its values, beliefs, and language to the children, one of whom is deaf and has been trained to read lips rather than sign. In Bach & Sons, whose world premiere is the first full-fledged play to be produced at London’s Bridge Theatre since lockdown, Raine returns to another struggling tribe, but here the impediment is genius.

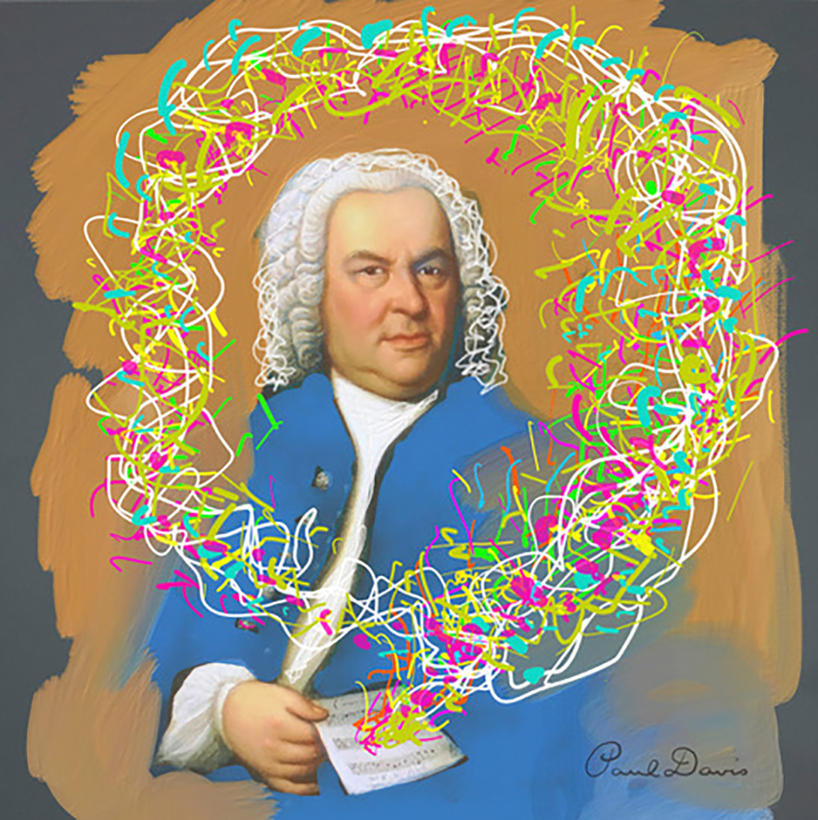

The paterfamilias in question is the dynamo Johann Sebastian Bach: music teacher, choirmaster, arranger, instrumentalist (keyboard and violin), and composer of more than 200 works for the organ and harpsichord, most of them masterpieces.

An irascible and restless soul, Bach (Simon Russell Beale) was a prodigious talent, whose gift for harmony was God-given and also God-inspired. Bach saw himself as a vessel as well as a virtuoso. “Music is a wonderful language,” he tells his balky, less talented teenage sons, Carl (Samuel Blenkin) and Wilhelm (Douggie McMeekin), both of whom he is educating in the family’s long tradition of music-making. But the conversation Bach is having through his music is with his God, not with his audience. “You have to do it for itself. For God,” he explains to his bemused first wife, Maria Barbara (Pandora Colin).

Genius is a fate, but joy is a choice. Faced with chaos and the caprice of family life—Bach had 20 children, 10 of whom died—he submerged himself in the heaven of harmonies, whose creation turned life’s anarchy into an ordered universe of resplendent sound. Raine’s theatrical challenge is to dramatize both the impact of Bach’s obsessive personality on his family down the decades and the mystery of his exquisite musical output. It’s a big theatrical lift.

“A fugue is a dramatic narrative. You can hear the same melody differently because of everything that comes between,” Bach, who composed The Art of the Fugue, instructs Wilhelm, his more talented and favored son. Bach continues, “The whole point is to combine two complementary or contrasting thoughts in the same moment.”

Bach was a prodigious talent, whose gift for harmony was God-given and also God-inspired.

Onstage, Raine tries to play Bach’s contrapuntal game. She uses the composer’s music to comment on a series of episodic, oblique, under-written scenes, a narrative shorthand to sketch both the trajectory of Bach’s career and his paradoxical nature: stingy and generous, arrogant and ashamed, pious and rapacious, loving and detached.

These contradictions are foreshadowed in Vicki Mortimer’s sly set, which fills the stage with the ordinary objects from Bach’s daily life—harpsichord, glass, chair, lamp, manuscripts—while above them is a surreal sky made up of miniature white harpsichords dangling at topsy-turvy angles like so many notes thrown on staff paper.

At the play’s first beat, Bach sits late at night at his harpsichord, noodling at a phrase that will become “And Sheep Will Safely Graze.” His wife enters to complain that the repetition is keeping their newborn awake. This quiet, seemingly incidental family moment presages Bach’s moral dilemma, and Raine’s larger existential inquiry: how to navigate the desire to be great and to be good.

Bach was certainly great, but good is another matter. Orphaned at the age of 10, he is self-absorbed, quarrelsome (jailed at one point after a clash with a bumptious bassoonist); foulmouthed (“They kiss you, then they fuck you,” he says of patrons); and most significantly, as his sons’ teacher, he is exacting, relentless, blunt, and bullying. “He annoys the fuck out of me, but he is brilliant,” Wilhelm tells Carl. For his part, Bach is just as confounded by his boys. “Why can’t I like any of my sons’ music? Why can’t I give comfort? I can do it in my music. Why can’t I do it for them?” he asks toward the end of the play.

As Bach, Russell Beale fits both his character’s roly-poly outline and his swiftness of mind. Beale is a powerhouse, a fecund master of his craft who understands the quicksands of artistic obsession and brings all that hunger and heartbreak with him onstage.

Raine’s theatrical challenge is to dramatize both the impact of Bach’s obsessive personality on his family down the decades and the mystery of his exquisite musical output.

He is never more poignant, nor the play more poetic, than when Bach tries to explain to his second wife, Anna (Racheal Ofori), about seeing his late first wife in a dream. “She’s alive but a long way away from me. Her face glows, but it’s fading. I blow on it to keep the fire alive.” Bach’s Chaconne calls Maria Barbara out of the shadows; he dances with the beloved memory. They sway in synch but never touch, making manifest Bach’s mourning through his music.

Theater is a game of show-and-tell. Since most of the inciting incidents in Bach & Sons happen offstage, the play is more tell-and-tell, an act of illustration, not penetration. Nicholas Hytner’s crisp direction guides the production around this structural pitfall with the sure knowledge that, when skating on thin ice, your safety is in speed. If Raine’s play lacks propulsion, it never lacks intelligence. In charting the story of the sons as well as of their mighty father, she unearths the envy that shapes and often destroys the lives of those who live under the long shadow of a distinguished parent.

Wilhelm becomes a drunk and a laggard, attacking both his own talent and his father’s aspirations for him. (Wilhelm, who lost some of his father’s scores, according to the play, also once signed his father’s name to a composition of his own.) By contrast, Carl can never find favor with his father despite his musical success. “At times you do a pretty good imitation of me” is Bach’s cutting musical assessment, a judgment that could also stand for Carl’s life, devoted to the impossible task of winning his unreachable father’s approval. “You are him, by the way,” Wilhelm tells Carl, adding, “I just got the bit that doesn’t get on with people.”

Raine is never more eloquent than when describing Bach’s wonder at musical form. She is ravished by Bach, and her love shines through the description of his technique. About counterpoint, for instance, Bach tells Carl, “Every line has another turn, another door, another direction, endless precipices, endless suspensions, it’s geometrical, it’s beautiful.”

If Raine’s variations on the theme of family sorrow and regret don’t resolve themselves quite so beautifully, the evening is full of articulate energy. That said, it is a bit strange to hear Bach accuse his son, in 1727 or so, of being “narcissistic” and “neurotic.” Bach may have been ahead of his time, but not that far ahead.

John Lahr is, among other things, a columnist for AIR MAIL