During the halcyon summer of 1967, London’s King’s Road was ground zero for the new global youthquake. Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton, and Michael Caine were regulars at the various ultra-hip bars and restaurants dotting Chelsea, the groovy U.K. equivalent of Manhattan’s Greenwich Village.

But the unsung star of the so-called Chelsea Set was Claudie Delbarre, a beautiful 18-year-old aspiring model, who claimed to have been sketched by Salvador Dalí. Wearing the most outrageous hippie clothes and sporting the shortest miniskirts, Delbarre dressed so provocatively that a policeman once warned her to tone it down for her own safety.

Born in the tiny French town of Tourcoing, on the Belgian border, Delbarre came to England after her mother died. She worked as an au pair in Yorkshire but soon gravitated to the bright lights of London, finding work as a hostess in a seedy Soho nightclub. She also turned tricks on the side, under the nom de plume Claudy Danniel, for well-healed clients including a Conservative M.P. and a bishop. She recorded their sexual predilections in her brown diaries for future use.

But the five-foot-one-inch Delbarre wanted to be famous. The ambitious blonde had recently signed up with West End modeling agent Ken Rose, who told her she had “fantastic potential as a model.” Already she had been snapped by top photographer John Cowan—whose Notting Hill studio had been used as the main set of Michelangelo Antonioni’s classic movie Blow-Up—for a photo spread capturing “Chelsea’s psychedelic mood,” in the American magazine Avant Garde.

“I was looking for something that definitely wasn’t routine stuff,” Cowan later explained. “You couldn’t help but notice Claudie! Weekend after weekend she would be walking up and down the King’s Road.”

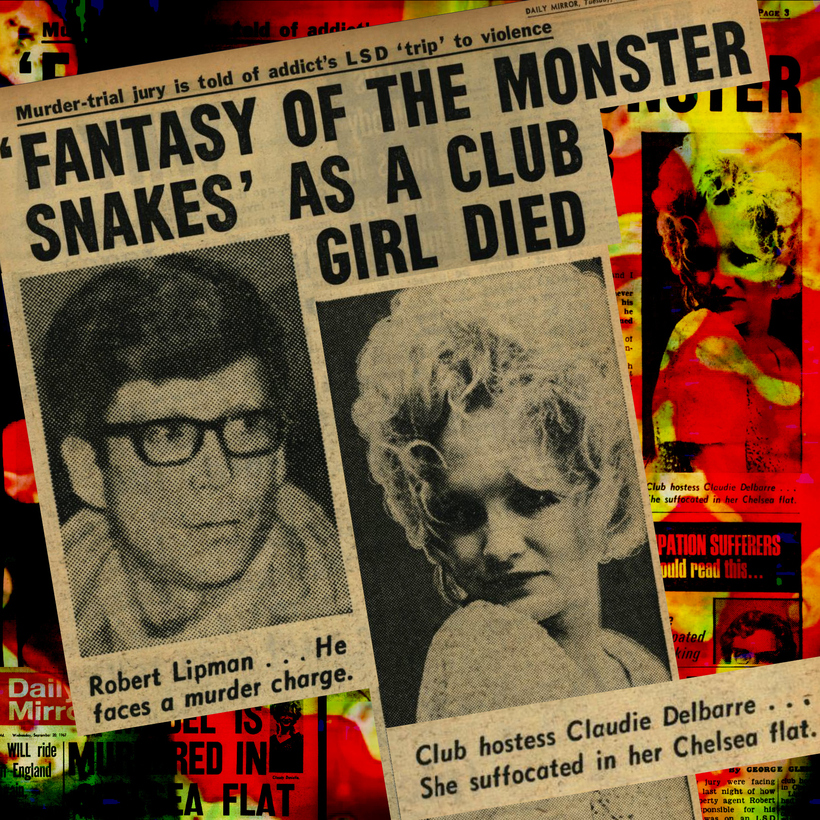

Delbarre had also set her sights on Robert Lipman, the ruggedly handsome, fabulously wealthy heir to a Manhattan real-estate fortune, who was six feet six inches tall and more than twice her age. They got high together and hung out at the exclusive Speak Easy club, frequented by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Jimi Hendrix. Delbarre told her friends that he would look after her, and that she would soon be living the high life.

The unsung star of the so-called Chelsea Set was Claudie Delbarre, a beautiful 18-year-old who claimed to have been sketched by Salvador Dalí.

It was a heady time in London, and anything seemed possible. The Beatles’ brand-new LP, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, was everywhere, and antique military uniforms, caftans, and granny glasses were the order of the day. And Delbarre was right in the middle of it all.

On the afternoon of Saturday, September 16, 1967, Delbarre left her shabby apartment off King’s Road to go shopping at Chelsea Girl, her favorite boutique. Dressed to kill in her new curly red beehive wig and secondhand raccoon-fur coat, she was looking to score some LSD for that night’s hot date with Lipman.

As she paraded down King’s Road, Delbarre was stopped by a camera crew from a television station preparing a news segment on Chelsea fashion. They filmed her going in and out of boutiques, showing off the radical new clothes.

Delbarre was ecstatic when she met some of her hipster friends outside the fashionable Picasso Café later. “She thought she had made it at last!,” said her best friend, Lucy Cardonvillis.

As she sat chatting with friends outside the Picasso, local photographer John Bignell passed by and asked to shoot the colorful group. His iconic picture would provide a perfect snapshot of that storied time and place, with Delbarre blissfully holding a bunch of flowers.

Within hours, the luscious Chelsea flower child would be savagely murdered, and Robert Lipman on the run back to America.

A Playboy Is Born

Robert Steven Lipman’s childhood should have been the stuff of Manhattan dreams. The multi-million-dollar New York City real-estate portfolio of his father, Abraham Lipman, included Fifth Avenue’s Flatiron Building and the Essex House, on Central Park South. Born on July 21, 1931, and raised in his father’s elegant 101 Central Park West apartment, Robert had everything money could buy.

“As a child he was so handsome and adorable,” said his younger sister, Grace Levison. “He was spoiled rotten by everyone.”

Yet, growing up, Robert always felt in the shadow of his father, who belittled him, constantly reminding him that he himself had made his first million before he was 21. By the time Robert hit that family milestone, he had flunked out of the University of Southern California with a debilitating alcohol problem and was struggling to keep afloat.

Everything changed in the fall of 1953 when he met the 18-year-old Houston heiress Lynn Sakowitz, whose family owned the renowned Sakowitz department-store chain. She was swept off her feet by the brooding dark-eyed giant, even finding his huge, rather ungainly nose attractive.

Their marriage the following year at Houston’s Temple Beth Israel was the Texas society wedding of the year. After a lavish honeymoon in Hawaii, Lipman moved to Houston to work in the Sakowitz department-store business, but he had little aptitude for it. Frequently drunk and missing for days on benders, he informed his new bride that he liked his women to look like prostitutes. Lynn dutifully obliged, dying her hair platinum blond and using bright-red lipstick.

“He was drinking when we got married,” she later explained, “and then he really started drinking … he was very immature.”

After Lynn gave birth to their first son, Steven, they moved to Palm Beach, so Lipman could try his hand at real estate, but that proved even more disastrous. Lipman now spent most of his time at the Racquet Club in Miami Beach, bedding the members’ wives.

In 1957, Lynn gave birth to another son, Douglas Bryan, and Lipman started becoming violent. Things became so bad that Lynn’s father, Bernard Sakowitz, arrived at their Palm Beach home while Lipman was away and took his daughter and two grandsons with him back to Houston.

Soon afterward, Lynn filed for divorce, later marrying the oil billionaire Oscar Wyatt, reputedly the model for J. R. Ewing of the Dallas TV show.

After the divorce, Robert Lipman got a nose job, bought a flashy Cadillac convertible, and moved into a bachelor apartment on Miami Beach. Then, in December 1962, Abraham Lipman died, aged 73, leaving his errant son a fortune.

Robert Lipman’s father constantly reminded him that he himself had made his first million before he was 21. By the time Robert hit that family milestone, he had flunked out of college with a debilitating alcohol problem.

With his father out of the way, Lipman devoted himself to hedonistic pleasure, traveling the world in search of a good time. Now in his 30s, he cut quite a figure with his great height, bushy, gray-streaked black hair, and horn-rimmed glasses. Wherever he went he had a ready supply of all kinds of drugs, and he was referred to by his friends as the “travel agent,” as he knew all the main dealers in Europe and America.

“I began on marijuana and amphetamine,” he would later explain, and soon moved on to “opium, methedrine, cocaine, and heroin.” He was also drinking at least a bottle of whiskey a day, and, after he started combining LSD and methedrine, became deeply paranoid and suicidal.

“Sometimes on an LSD trip I felt so bad and rotten about myself,” he said. “I did not care whether I lived or died. I was just completely disgusted with myself.”

He was now constantly on the move, trying to escape friends he believed posed a danger. “I left Spain because I was afraid there was a plot to kill me,” he once admitted.

Lipman devoted himself to hedonistic pleasure, traveling the world in search of a good time.

On September 4, 1967, Lipman landed at London Heathrow looking for new kicks. He checked into the Knightsbridge Green Hotel, arranging to meet some old friends at the members-only Alvaro’s restaurant on King’s Road, where regulars included Princess Margaret, David Bailey, and Sammy Davis Jr.

On previous visits to London, Lipman had charmed his way into the Chelsea Set by spreading his money around. His new clique included rock star Viv Prince, the former drummer with the Pretty Things, as well as actors Benny Carruthers, who had just finished filming The Dirty Dozen, and Iain Quarrier, then working on Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers.

“Bob always picked up the tab and was happy to be included in the Chelsea fringe,” said theatrical agent and author Mim Scala, who chronicled the 1960s King’s Road scene in his book Diary of a Teddy Boy: A Memoir of the Long Sixties. “He seemed to have a bit of money to spend and was enjoying himself.”

A few days later he was at Quarrier’s flat in Walpole Street, off King’s Road, when he saw Claudie Delbarre, who lived opposite, walking across the road and waving. Lipman and his friends invited her over, and after smoking some dope, Lipman easily seduced her, and they started seeing each other.

The Beginning of the End

Robert Lipman spent Saturday, September 16, getting high with his Chelsea friends. Around 11 that night, Lipman met Delbarre and nine other friends for dinner at the Baghdad Restaurant on Fulham Road. After the meal they all split up, agreeing to meet later at Speak Easy.

Lipman went back to his hotel to change into something hipper—a suede shirt, flared jeans, and Chelsea boots. Then he took a taxi to Speak Easy, where he reunited with Delbarre, who had changed into a sexy black minidress and a string of pearl beads. Lipman bought everyone a round of drinks, and then he and Delbarre danced to Pink Floyd, who were playing onstage that night.

They left around 3:30 A.M., and Delbarre asked Lipman if he had any LSD. He said he did, and they went back to her flat to drop the “great acid from America” Viv Prince had sold him earlier that day. “She said she would put the kettle on and to make myself comfortable,” said Lipman. Then they undressed, took the LSD, and started making out on her divan bed.

“[I] kissed her and put my arms around her,” Lipman later remembered. Then “the trip started.”

What happened next only Robert Lipman and Claudie Delbarre will ever know. Perhaps Lipman was too stoned to perform and Delbarre laughed at him, causing his always fragile psyche to snap.

What is clear, though, is that Lipman viciously attacked Delbarre as she desperately tried to fight back. But the diminutive teenager stood no chance against the powerful giant. In a wild frenzy he smashed a heavy glass tumbler over the left side of Delbarre’s head twice, causing a cerebral hemorrhage. She was already dead when he furiously rammed eight inches of her thick blue bedsheet down her throat to finish the job.

“Sometimes on an LSD trip I felt so bad and rotten about myself. I did not care whether I lived or died. I was just completely disgusted with myself.”

What’s also clear is that after the savage killing, Lipman methodically searched Delbarre’s flat, finding dozens of her naked photographs, and reading her three brown diaries and 200 love letters, which he threw around her living room.

Lipman spent 28 straight hours inside Claudie’s flat, before finally leaving at around 9:30 on Monday morning. A very tall, disheveled man was then seen running back to his hotel, where he immediately checked out.

Lipman then grabbed a taxi to the Cedars Travel Agency in the West End, buying a one-way airplane ticket on the first available flight to Copenhagen, at 12:40 P.M. During the cab ride to the airport, Lipman seemed composed and made small talk with the driver, Denis Murphy.

“I could tell from his accent that he was American,” Murphy later testified. “I asked how he liked London and English beer. He said he preferred halves of bitter and barley water mixed, as ‘they’ve got a real kick in them.’ Then he added, ‘And I’ve sampled some of the English girls too.’”

What happened next only Robert Lipman and Claudie Delbarre will ever know.

On Tuesday morning, several unanswered calls were made to Delbarre on the public pay phone in the hallway downstairs. When someone finally knocked on her door, there was no response. Then a neighbor said he had not seen Delbarre for more than three days, which was highly unusual, as she was in and out all the time.

Her landlord finally let himself in with a master key and called the police, who uncovered Delbarre’s naked, battered body lying under a bedsheet on her divan bed, the blue sheet stuffed down her throat. On a chest of drawers near the bed was her wig, carefully placed on a mannequin-head stand.

The next morning, Claudie Delbarre’s murder made front-page headlines. Model is Murdered in Chelsea Flat – Yard Probe Riddle of Half-Naked Blonde, screamed the Daily Mirror.

Over the next few days, a 70-strong murder squad from Scotland Yard did the rounds of all the King’s Road nightclubs, showing pictures of Delbarre. Detectives also set up a mobile police station outside Speak Easy, interviewing everyone who had been there Saturday night, including rock stars Jimi Hendrix, Dave Clark, and Keith Moon.

Police also interviewed Delbarre’s friends, including Lady Henrietta Guinness, Benny Carruthers, and Iain Quarrier, who, like Delbarre, were Speak Easy regulars. “I was with my chauffeur at the time,” Lady Henrietta told the New York Daily News. “The police … even bought me a drink after I had spoken to them.” Detectives, meanwhile, interviewed nine of Claudie’s wealthy “sugar daddies” after finding their names in her diaries. No leads materialized.

Then a piece of the shattered glass tumbler found under Delbarre’s bed was tested for fingerprints, and it led straight to Robert Lipman, who’d been arrested for possessing cannabis several weeks before the murder.

Retired Chelsea police officer Trevor Binnington, who worked on the case, says that although Lipman’s friends had suspected him of killing Delbarre, nobody wanted to point the finger at him.

“The Chelsea clique tried to tell us who had done it by holding a séance,” said Binnington. “They didn’t want to tell us directly who had murdered Claudie, so they had a medium pretend it was coming from beyond the grave.”

The Moment of Truth

After fleeing back to the U.S. from Denmark, Lipman had checked himself into the Institute of Living hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, paying $1,200 a month ($10,500 in today’s money). It was an exclusive psychiatric facility favored by film stars and Broadway performers, as it guaranteed maximum privacy.

Scotland Yard detectives enlisted the help of the F.B.I., who soon traced the fugitive to the mental hospital, where he said he was too sick to be interviewed.

On January 24, 1968, the British government obtained a murder warrant for Lipman’s arrest and extradition back to London under a reciprocal 1935 treaty for capital offenses. Ten weeks later, Lipman was formally arrested in Hartford, before being transferred to a Federal Penitentiary hospital in Danbury.

At the end of April, Detective Chief Inspector Fred Lambert of Scotland Yard brought Lipman back to London to face first-degree murder charges, after Dean Rusk, secretary of state under President Johnson, personally approved the extradition order.

Detectives set up shop outside London’s Speak Easy nightclub, interviewing Jimi Hendrix, Dave Clark, Keith Moon, and others who’d been there the night of the murder.

On October 7, 1968—almost 13 months after Delbarre’s murder—Lipman’s high-profile trial began at the Old Bailey. It was big news on both sides of the Atlantic.

The multi-millionaire defendant’s dream team of defense lawyers, led by Sir Michael Eastham, Q.C., would plead innocent and claim their client murdered Delbarre while out of his mind on LSD. It was a revolutionary psychedelic defense, which would make British legal history, as it was the first time it had ever been used.

Eastham’s dramatic opening statement certainly got the jury’s attention. “I have to take you into a world which will be wholly unfamiliar to us,” he began, as his client, dressed in a smart black suit, crisp white shirt, and dark tie, sat impassively at the defense table. “You will hear about amphetamine, opium, cannabis, amyl acetate, cocaine, heroin, LSD, STP and DMT. It is a very sordid, unrewarding and self-destructive world we have to go into.”

Delbarre’s landlord, Mark Trevelyan Shaw-Lawrence, then took the stand, describing Delbarre as a good tenant, who always paid her nine-guineas-a-week rent ($225 today) promptly. “She had a lot of friends who used to call at the house,” he told the jury. “The men had long hair but I never had any reason to object about their conduct.”

Then Detective Chief Inspector Lambert was cross-examined by Eastham, who was determined to paint his client’s victim in the worst possible light.

“As a result of your inquiries,” he asked Lambert, “are you satisfied, first of all, that this young woman of 18 years of age was taking hard drugs?”

“There is no doubt at all about this,” he replied.

“The next thing I want to ask you is this … are you satisfied that she had slept with a very large number of men?”

“Yes, she was a prostitute,” answered the detective.

“For money?”

“Yes.”

Then Eastham called Lipman to the stand and asked what happened after he and Delbarre took the LSD that fateful night. Lipman told the jury that they had started kissing but he was too stoned for sexual intercourse. “It was as if I’d gone dead in that part of my body,” he explained.

“It was like I was on an electric current or electric circuit,” Lipman continued. “It was very weird and I was quite alarmed.... I plummeted down towards the earth which opened up and I found myself going right down into the centre of the earth, found myself in a pit of snakes … they were entwining themselves around me, fire was coming out of their mouths, and I realized I was in Hell fighting for my life.”

Eventually, he claimed, he came out of the trip to discover Delbarre lying dead on the bed. “I shook her and tried to move her,” he said. “I didn’t get any response from her. I knew something amiss had occurred.” He said he then panicked and rushed out of her flat in a daze.

“At any time did you want to kill Claudie Delbarre?” asked Eastham.

“Definitely not,” Lipman replied.

He claimed he had left 17 Walpole Street early Sunday morning and spent the rest of the day between Hyde Park and several pubs, before checking into a private hotel in Shepherd’s Market. His version had earlier been refuted by secretary Susanna Goodbody, who testified that she’d seen him running down Walpole Street toward King’s Road on her way to work during Monday morning’s rush hour.

Under cross-examination by prosecutor John Mathew, Lipman said he had taken between 15 and 30 LSD trips since 1965. He claimed he had never been violent before and had no idea what had happened to Delbarre and how she had died.

“Did it ever occur to you for a single moment,” asked Mathew, “to go to the police or ring up the hospital authorities?”

“Yes, sir,” he replied.

“Did you dismiss it from your mind?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“I was afraid of police brutality,” he explained.

Then the prosecutor asked the defendant about Goodbody seeing a six-foot-six-inch man running away from Delbarre’s building on Monday morning, and identifying Lipman from a photograph.

“I swear it was not me,” he replied.

“Mr. Lipman,” asked Mathew, “you didn’t stay in that room with Claudie Delbarre for very much longer than you have told us, did you?”

“No, sir,” Lipman replied.

Addressing the jury, the Old Bailey judge Sir Helenus Milmo stated that if they accepted that the defendant had killed Delbarre under the influence of drugs, it would lower the murder charge to manslaughter. The elderly judge appeared highly sympathetic to the wealthy defendant and deeply critical of the victim’s lifestyle.

“If Lipman was in the condition that he has told us about this horrible trip provoked by drugs,” Milmo told the jury, “you will probably come to the conclusion that he was not capable of forming any intention against her at all. His mind was not merely befuddled but it virtually did not exist, because it was completely irrational.

“I swear it was not me.”

“But you must keep in mind that Claudie Delbarre, although she was a prostitute, is entitled to the same protection as the most virtuous and important person in the land.”

After a brief deliberation, the jury found Robert Lipman guilty of manslaughter, and Milmo sentenced him to six years in prison, with a recommendation that he be deported back to America after serving his sentence.

While Lipman was behind bars in Wormwood Scrubs prison in West London, his friend Mim Scala visited him several times, asking what had happened to Delbarre. “We were all terribly shocked,” said Scala. “Although he was guilty, it was a crime that was not committed in malice. [He took] one acid trip too far and lost the plot. An unfortunate ending to what in those days should have been a beautiful psychedelic evening.”

On February 1, 1971, after serving just over two years in jail, Lipman was freed on a reduced sentence and sent back to the U.S. For the next few years he kept a low profile, occasionally being seen at society parties at New York’s El Morocco nightclub.

Lipman was in and out of drug rehab until he died in a Vienna streetcar accident in April 1981, at the age of 49. His ashes were sent back to his estranged younger sister Grace Levison for burial.

“So there I was, stuck with the remains of my brother,” Levison later told Detroit Free Press columnist Shirley Eder. “I loved Robert but he was always trouble. Our father had fortunately died before the murder and scandal.”

Eleven years later, Lipman’s eldest son, Steve Wyatt, made global headlines himself, after his torrid affair with Sarah Ferguson broke up her marriage to Prince Andrew.

John Glatt is the author of several books, including Golden Boy: A Murder Among the Manhattan Elite, which he wrote about for AIR MAIL. His latest book, Tangled Vines: Power, Privilege, and the Murdaugh Family Murders, will be published on August 8 by St. Martin’s