“Hi-Yo, Silver! For generations of juvenile TV fans since 1949, the “William Tell Overture” was synonymous with The Lone Ranger, all 221 episodes of it. In fact, the series’ hard-charging theme music—officially “The March of the Swiss Soldiers”—is just the finale of Gioachino Rossini’s four-movement pops classic. For the complete overture and the sorely neglected historical fresco that follows, check out the full-length William Tell as captured on live video at Milan’s fabled Teatro alla Scala in 1988, three seasons into Riccardo Muti’s historic 19-year tenure as the institution’s music director.

The last of Rossini’s three dozen works for the stage, William Tell opened in Paris in 1829, almost exactly midway through what would prove a good long life, well lived. The composer’s first act (think The Barber of Seville) transpired mostly in Italy, where he churned out operas by the dozen; his second (think Tournedos Rossini) found him settled in France as a world-class social lion and bon vivant. Eventually, the master returned to his desk for the major sacred work he perversely called the Petite Messe Solonnelle, as well as 14 volumes of salon pieces he called his Sins of Old Age. But never again after William Tell would he write for the theater.

A heroic pageant of Switzerland’s founding in 1291, William Tell epitomizes French grand opera at its grandest, unfurling Alpine vistas and landscapes of the heart in lavish instrumental gestures and colors that owe no small debt to Beethoven. Muti’s uncut account of the score—nearly four solid hours of music—delivers the pictorial detail and symphonic sweep with the force of revelation.

Electricity matters, for in truth much of the narrative unfolds little faster than a densely peopled suite of waxworks, supercharged with dramatic implication, yet short on actual drama. “Don’t move,” the anguished hero implores his boy at the climax, preparing to aim his crossbow at the apple a wicked foreign tyrant has had placed on the child’s head. No-nonsense but noble, underscored by an eloquent cello cantilena, the baritone Giorgio Zancanaro lends his dread a flinty eloquence.

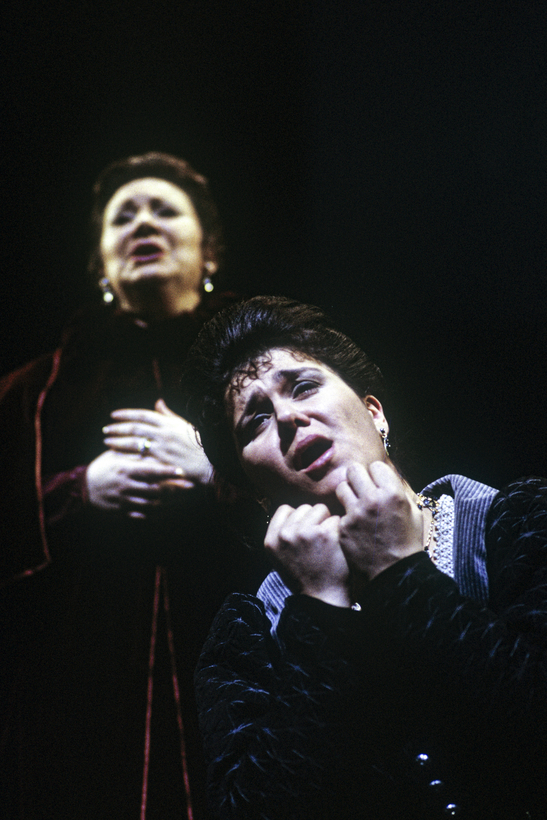

As Tell’s boy Jemmy, the mezzo-soprano Amelia Felle conveys pluck and filial pride. As Tell’s wife Edwige, the mezzo-soprano Luciana D’Intino leads the women’s chorus in a sublime prayer for her husband’s life as he braves in a fragile rowboat the whipped-up waters of the Lake of the Four Forest Cantons. Love interest with its star-crossed ups and downs focuses on the Austrian aristocrat Matilde and the young Swiss revolutionary Arnold, bravura parts the soprano Cheryl Studer and the tenor Chris Merritt invest with exhilarating panache. The chorus of Swiss confederates, likewise, consistently rises to Rossini’s huge challenges, be it in moments of a hushed conspiracy in the mountains, or in full-throttle celebration of their hard-fought liberty.

Two caveats. The archival sound at peak load requires a listener’s forbearance. Also, the work is sung in Italian translation rather than the French original, a choice that might not fly today but at the time and that house was not especially controversial.

William Tell is available for streaming on Teatro alla Scala TV

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii