The Belgian sculptor Berlinde De Bruyckere works with waxed animal skins, bone, wood, and wool to create haunting works that drift between divine realms and the dailiness of living. In 1988, for her very first exhibition, she paired blankets with furniture to convey feelings of shelter and security. In 2000, she placed five life-size casts of dead horses in Flanders Fields, in Ypres, a site of epic bloodshed during World War I.

Over the years, De Bruyckere has continued to use organic materials, often monumentally scaled, in her studies of death and transcendence. In the exhibition “Berlinde De Bruyckere: A Simple Prophecy,” on now at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich, De Bruyckere brings sculptures from her recent “Arcangeli” series—cast in bronze and lead, and raised high on plinths—together with wall reliefs from her 2018 exhibition “It Almost Seemed a Lily.” AIR MAIL talks with the renowned artist.

Elena Clavarino: As a child you were fascinated by the art of Lucas Cranach the Elder. What was it that so struck you about the German Renaissance painter?

Berlinde De Bruyckere: I saw this extraordinary transparency in the way he painted human flesh, so fragile and delicate. His bodies were never perfect; there was always some deformation, which added something mystical for me. I try to implement this approach in my wax pieces. It’s a very painterly way of sculpting.

E.C.: You use many organic materials. How do you choose which inorganic materials come into your art, if any?

B.D.B.: It’s not really a deliberate choice. When I’m in front of a dead tree or a huge carcass of a dead horse, there’s something that attracts me to translate it into sculpture. But during this process of “translation” many elements enter the work, both organic and inorganic. What you see is just the outer shell. There’s always a complicated structure underneath.

E.C.: Do you always feel you can create? Or is a subject sometimes too tough to face?

B.D.B.: People often say, “Your work is much too cruel, it’s violent.” And my reaction is always, “You should look closer.” When you look at the body of a dead horse on an iron table, it’s cruel because you’re not used to seeing bodies of dead horses. For me, these horses started out as metaphors for death during the Great War, when humans became anonymous. In war times, then as well as today, we are no longer Berlinde or Elena, we are just numbers, casualties. For me the scale and the inherent innocence of such a monumental animal embodies the atrocity of such a situation.

E.C.: So it gives people a realistic perception of the world around them?

B.D.B.: The world is crueler than I am. I try to give comfort and hope. Of course, at first glimpse my work can be very violent and aggressive. But when you look better, you’ll see different layers, the beauty and the vibrant power of the bodies, elements of nurture and care.

E.C.: What is another way to look at it?

B.D.B.: Exactly these soothing elements. The wax, for instance, is very delicately painted; it’s a soft material that has a radiant beauty to it. To me, it brings out the frailty and preciousness of life rather than thoughts of death. The same goes for the skins of the horses, or the trees I cast. The elements I add, like the blankets, provide consolation and warmth.

“At first glimpse my work can be very violent and aggressive. But when you look better, you’ll see different layers, the beauty and the vibrant power of the bodies, elements of nurture and care.”

E.C.: Has anyone ever told you that one of your works or your art has changed their view of death, or made them less afraid to die?

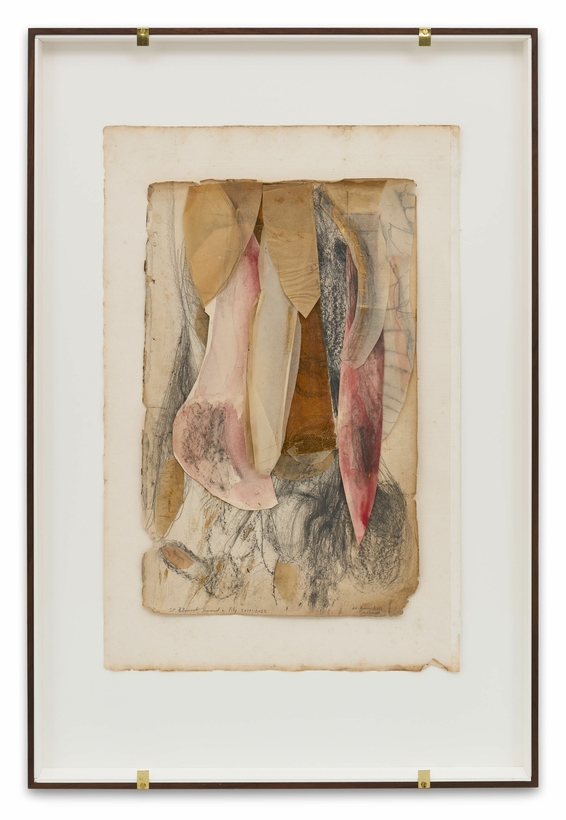

B.D.B.: People can relate to this beauty in decay, yes. Memento mori is a beautiful term in this respect. My series “It Almost Seemed a Lily,” which is in the exhibition, came from my own memento mori. Years ago, I bought lilies for my house. They were fresh and closed. When they opened, the smell was overwhelming. Then the flowers started to lose their petals. They were falling on the table. They became so fragile and dry and so close to human skin. I took photos of lilies for years and ended up casting animal skins to create the large flower petals for these wall works.

E.C.: You were also inspired by the Enclosed Gardens of Mechelen.

B.D.B.: Yes. I saw these gardens, these little cabinets, for the first time in an exhibition in Leuven. They were so beautiful. The Augustinian hospital sisters used them for their private rooms, like small Gardens of Eden. From the moment they entered the cloister the sisters didn’t go out anymore; they stayed there nursing the sick until they died. These were boxes full of memories and secrets, which represent whole lives and generations of women.

E.C.: Tell me about the “Arcangeli” series.

B.D.B.: The first time I showed people the Arcangeli, they said, “Oh, but these angels are dark.” I’m not interested in recreating the traditional angels we see in paintings. I want to make new angels, which feel more human. The Arcangeli are mysterious, their faces are covered by draped animal skins. This can be perceived as dark by some, but my experience is that this absence of a face, and consequently a clear identity, is liberating. It’s free of judgement somehow. People can project their burden onto these faceless creatures that seem to accept their fears, anger, and secrets silently and store them under their cloaks.

“A Simple Prophecy” is on at Hauser & Wirth, in Zurich, through May 13

Elena Clavarino is the Senior Editor for AIR MAIL