Christie’s specialist Noah Davis studied absurdist theater at New York University. After more than six years at the auction house, he finds himself returning to Ionesco. Davis envisions The Chairs as a metaphor for the 21st-century art scene in which he lives.

“The protagonist is a philosopher who’s going to reveal his amazing life-unifying theory. He’s invited all these people to the event,” Davis says. “But they’re just chairs; they’re just empty chairs in a room.”

That emptiness speaks to what Davis calls “this plague year,” and the coronavirus’s impact on all aspects of life and luxury. The elite art-world microcosm of salespeople and lavish parties, complete with its tangible, two-dimensional works, has been replaced by laptop screens and virtual auctions, with shared experiences lived exclusively in the ether. With this comes something revolutionary: the first crypto-artwork ever to be sold at Christie’s, or at any traditional auction house, in history.

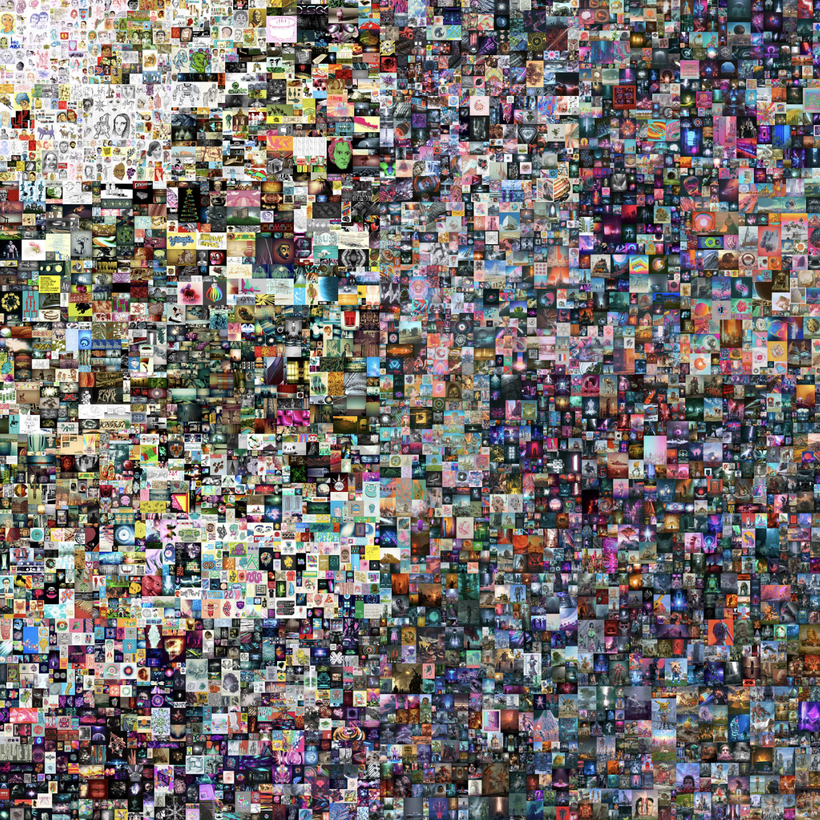

The work is Everydays: The First 5000 Days, by digital artist Mike Winkelmann, who goes by the name of “Beeple.” It opened for a single-lot sale on February 25 at just $100, listed simply as “Estimate unknown.” Since then, the work has been bid up to $3.5 million. Bidding will continue until the sale on March 11, at which point payment in “Ether,” a crypto-currency similar to Bitcoin, will be accepted by the collector.

What makes Everydays crypto-art is not just that it resides in the digital sphere, although it does—a collage of 5,000 digital pictures, one from every day of more than 13 years of the artist’s life, the work is viewable only on-screen. It gets its “crypto” label from its existence as a non-fungible token (NFT) on the blockchain—meaning it has a unique code attached to it that allows for its buying and selling with crypto-currency, as opposed to the dollars we’re used to.

Mystery Money

Those literate in crypto-art are often digital natives, children of the Internet who have matured with the space. Until recently, the exchange of crypto-currency (and the blockchain technology upon which it was built) was sort of the financial equivalent of the hipster band you’ve probably never heard of. Few understood it, let alone possessed the courage to buy and sell with it.

Today, though, crypto is quickly going mainstream, with some of the world’s highest-profile businessmen, including Gary Vaynerchuk (co-founder of restaurant-reservation app Resy), Mark Cuban (owner of 2929 Entertainment as well as the Dallas Mavericks), and Elon Musk buying in. Musk made headlines last month for sinking $1.5 billion of Tesla money into Bitcoin, announcing the company would accept it as payment. His endorsement shot the value of Bitcoin up to record highs, even as Tesla’s shares subsequently tumbled in tandem with the volatile tech market.

Until recently, the exchange of crypto-currency was the financial equivalent of the hipster band you’ve probably never heard of.

While it’s hard to imagine assigning similar worth to a digitally created work as it is to, say, a Raphael, works like Beeple’s were painstakingly created over more than a decade. Everydays is intensely personal, juxtaposing the intimate emotions of family and individual experience with the macro world of political and economic malfeasance. The 5,000th work, created just five weeks before the sale, depicts the artist’s childhood self merging with extremist political caricatures of Kim Jong Un, Michael Jackson, and Donald Trump looming in the background.

And though you might not appreciate something as much on a screen as you would in person, crypto-art simplifies a lot of the art world’s biggest problems, unequivocally clarifying an artwork’s provenance by encrypting it in its code, says Garrette Furo, an up-and-coming crypto-art collector, consultant, and investor.

Furo began collecting crypto-art in 2017—not digital works but traditional, physical art that had certified its ownership and proof of authenticity through a non-fungible token. But creating tokens for buying and selling traditional art with crypto-currency was not synonymous with digitized art just yet. That has only just started.

Crypto-art simplifies a lot of the art world’s biggest problems, unequivocally clarifying an artwork’s provenance by encrypting it in its code.

In January of 2018, the online auction house Paddle8 announced it would accept Bitcoin for works in its auction that summer. Christie’s sale later that year, of the $323 million Barney A. Ebsworth collection of 20th-century American art, cemented blockchain technology’s place on the map. Christie’s registered all 42 of the collection’s lots with Artory, a blockchain-encryption company founded by C.E.O. Nanne Dekking, and it became the auction house’s first-ever digitally recorded sale.

Dekking, formerly the head of private sales at Sotheby’s and chairman of TEFAF (the European Fine Art Fair), is enthusiastic about the potential for more intersection between traditional art and crypto-art with this month’s Beeple sale.

Dekking shares Garrette Furo’s appreciation for the transparency that crypto-art provides. Utilizing blockchain technology, the provenance of an artwork is permanently encrypted, impossible to cover or muddy up. Think of it as a record book that’s incorruptible—and a good-bye to the legendary forgers of yore. With this certainty of origin and legitimacy of the transaction, Dekking believes that the trading opportunities for art will be vastly improved.

“You can’t fake that,” Furo echoes. “It’s essentially impossible.”

As efficient and finite as it is, the crypto-world is undoubtedly complex and confusing, especially for old-schoolers who still carry cash in their wallets. “Probably the most frequent question is: What am I actually bidding on?,” Davis says. “What am I winning? How am I displaying this in the future? What do I get?

“The answers are going to be dissatisfying if you’re a traditional art collector and you’re expecting something you can hang on your wall,” he continues. “To be told what you’re getting is just a long stream of numbers and letters that lands in your digital wallet, you know—” he laughs. “It’s really hard to wrap your mind around that.”

Christie’s is comparing Beeple’s work to the Duchampian ready-mades that dropped chins in the early 1900s as an anchor to its art-historical significance. “Look at the traditional market,” Dekking explains. “What’s successful there? Success means there’s credible information. Success means really great scholars endorse the value of the market player, et cetera.” With blockchain encryption, you have those guarantees.

The future for this art form remains uncertain. Davis, Dekking, Furo, and other art-world players believe crypto-art is here to stay—in the days since the Beeple went on sale at Christie’s, the artist put works for $1 on a crypto-marketplace called MakersPlace and crashed the site. And contemporary artist Damien Hirst has announced he would be accepting crypto-currency at the HENI Leviathan gallery for a new set of his prints.

Furo imagines a future of digital free ports; Dekking, a new world of tech-minded art collectors who pivot from NFTs to the traditional art world. And Davis? He remembers the empty seats of The Chairs. As alien as this newfound world of crypto seems, it’s really just a continuation of the absurd reality that is the current art world, which puts prices on pieces that objectively have no value.

Christie’s New York will auction Beeple’s Everydays on March 11

Alexandra Bregman is a New York City–based writer