Sober birthdays are weird. September 15, 2024, was the ten-year anniversary of my giving up booze. Hello, the woman who has a home, a dog and a partner, who leaves the house in daylight, boasts a sofa she has actually sat on and flat shoes in which she can stride. Farewell, the lone, forever renting party girl who worked by day and caroused by night, the last at any bash and the first to parkour up a wall in heels.

Part of you wants to mark the occasion with a drink because this is what we do in our alcophiliac society. We celebrate with a drink and we commiserate with a drink. We drink because we’re excited, we drink because we’re bored, we drink to buoy ourselves up and we drink to uncoil. We drink to sleep and to shag, to feel and not to feel. We drink because it’s been a long day, a long week, a tough year, and we drink, in the end, because drinking is what we do.

For the newly boozeless—roughly the first four years—sober anniversaries also bring a contradiction. “If I can give up this long, then I clearly don’t have a problem,” runs the thought process. Leading, as ever, to the solution: “Drink.” My first sober milestone—100 days—occurred on Christmas Day 2014. “Have a glass of champagne!” cried the wassailing world. “Do you want a glass?” asked a fellow former drunk. “Do you want two glasses, a bottle, even?” He was right. I wanted a bottle of fizz, followed by a bottle of red, which meant I must continue having nothing.

So yes, sober birthdays are weird. And this, my tenth, is the weirdest yet. No one is more staggered than myself. Who am I if I don’t drink, an activity I pursued for 30 years: the highlight of every day, every occasion and thus my life? Part of me still misses her, that wild, roaring girl for whom life was a dazzling adventure, a constant escapade. The fearless heroine of scrapes, she had places to go, tales to tell. She was awesome, fabulous, terrifying, scaring even myself—especially myself—always skating on thin ice or leaping into pools fully clothed.

Fun, up to a point, but also intolerable: intoxicating company for a night, impossible company any longer, for me or anyone else. I was using alcohol to fuel an extrovert persona, conceal my introversion and self-medicate my depression. Then, coming home to UDIs (emergency room-speak for unidentified drinking injuries) and suppurating self-loathing.

I can still pass for extrovert; still boast the loudest laugh in any room. If anything, my balls of steel are steelier. Now I don’t have to be scared of myself, I’m not scared of anything. This is fortunate, as being teetotal means no escape from emotion: instead, feeling the feelings, as I learned during my first and second year of sobriety when my mother, Pam, then my father, Tim, died, and died savagely. My mother of a sudden, black and engulfing cancer, my father—well, read on.

Sitting with suffering isn’t easy after a lifetime of evading it via the bottle. Still, the thing I remain most grateful for is not putting my own sodden solace ahead of being present for my dying parents. Their deaths got to be about them, not their offspring’s emotional avoidance. I think of the night early on that my mother thought her last, when I was the only one at home sober enough to go and sit beside her in her agony.

In the past I have been asked to write about my sobriety according to the breezy formula: “I stopped drinking and was granted every woman’s dream,” a sort of glossy-magazine approach that implies, “Renounce the mother’s ruin and you too will be rewarded with a beautiful home, hound and partner.” And it’s true I wouldn’t have these things if I hadn’t stopped boozing. I met my partner, Terence, 90 days into abstinence and he would not have been interested in permanent-bender me, nor I in beautifully balanced him.

But sobriety has to be its own reward, just as girl-gets-man is an anachronistic view of success. There’s no happy ever after, only ever one day at a time.

When I met Terence at a Christmas party, I was presented with two men: one all blasted chaos, the other studied calm. I’ve always been an extremist, 0 or 10. Terence is a 5, moderate. At first, I found this impossible to read. It seemed flat, featureless. Plastered me would have rolled my eyes and walked away. It’s taken time to interpret this fiveness not as “boring” but stable. Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Without beer goggles I chose differently, and continue to make that choice today.

A friend can only understand my renunciation of booze in the context of my never mourning it. “And you never miss it!” is his refrain. In this scheme I made my decision, then never desired a drink again. AA posits a similar narrative: you work the steps—aka “doing the work”—then you cease to crave. I miss alcohol all the time. Recently friends were fantasizing about a crisp glass of white and I joined them in this longing.

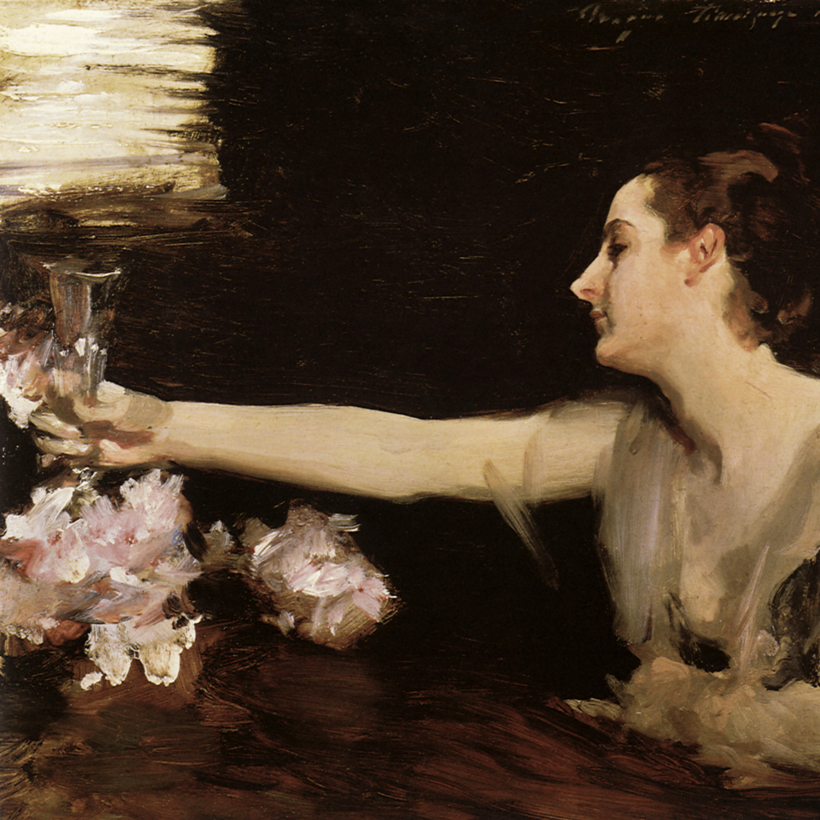

I loved drinking; I loved the accessories and the accoutrements and the clink of ice against glass. Only last week I had to stop myself purchasing a vintage cocktail shaker. It was just so bloody beautiful. I was smitten by the paraphernalia and the people, the venues and the venery; the fizzing up nostrils and immortal knockings back. I adored the very language used to describe intoxication: trolleyed, smashed, loaded, wrecked, slaughtered, hammered, wasted, trashed. Normal life was dull; booze life heroic.

I loved drinking, but I’ve had to learn to love other things more: my sanity, my self-respect, my fundamental quality of life. Friends will be happy with a glass, even if this translates as two. I won’t. And that means I shouldn’t drink at all.

And then there’s another element to my sobriety that I feel forced to acknowledge. I attended a state-of-the-art medical establishment earlier this year and my test results were first rate. This would be positive by anybody’s reckoning. However, it’s even more significant for me as both my parents fell prey to addiction—my mother food and my father drink—and both died relatively young.

My father was my model in all things. We drank together from my teens, bonding over our appetites. He was proud of my epic boozing, as I was of his. It was the mark of our generosity, of our rebelliousness, of living life. It also killed him.

My father always said he would drink himself to death once he finished being a doctor and that is what he did before he quite finished, timing alcoholism’s onset being difficult to achieve. When I lamented to friends that this was what he was doing, they would berate me for being a killjoy, telling me that drowning oneself in booze was a bloody good way to go. It isn’t.

What drinking yourself to death means is a career-ending stroke at 63, after others that you ignored. It means the slow obscuring of your planet-sized brain in alcoholic dementia, privileging your addiction above your life’s work, those you love and any last remnant of human dignity.

Of course, we endeavored to stage interventions, as the terminology goes—an enterprise in which ironically I took the lead. Of course he mocked us—those intervening also drank like maniacs, just younger maniacs, less far down the road of kamikaze addiction. “Let me go to hell in my own way,” he told us. And we were forced to.

There is a lack of sympathy in this type of demise because you appear to be bringing it upon yourself, not least when your partner is doing everything she can to survive. Infantilized by his condition, my father went through a stage of threatening to “run away,” furious at his family’s refusal to let him drive (he no longer had any idea where he was going, a danger to himself and to others). One morning, waiting for a taxi to take us to see my mother in hospital, he repeated this plan. Bone weary, I told him that, if he did, I would call the police; the most brutal I had ever been. Our visit was lacerating, she barely able to look at him, he clumsily oblivious.

On the return journey I felt incredulous with despair, patiently explaining to this former world leader in brain medicine why certain things were impossible, as one would to a child. Once parked, the driver sprang out of his seat and raced round to shake my father’s hand, commending him on his parenting, telling him he’d never witnessed a more loving “child” than my 43-year-old self. Again, I was incredulous, this time with gratitude that love—not rage—was what had been conveyed.

But there are a thousand mortifications in this sort of end. The ones that linger are the ones that horrified me. The small balls of black shit that started appearing—do we have rabbits? The constant head injuries incurred by this former brain expert forever plunging downstairs and onto his skull. The impossibility of respecting someone’s right to live as they wish while not allowing their situation to become one of neglect.

Three weeks before his death in July 2016, my father found he could drink no more. His body was too broken. My old father returned, coming round from his dipsomaniac fog. He didn’t want alcohol, didn’t shake or see things. However, unable to fill himself with comfort from the inside, he sought to immerse himself in it from without, starting to take 12, 24, 48, even 72-hour baths, submerged in warmth and shit. We pleaded with him to let us help him, threatened to summon social services. But he was as dogged as ever.

On the final day of his life, his carer, my poor brother, left him alone in the bath for a few minutes. On his return, my father was dead. Our Victorian hot-water system had been aggressively overheating. He had turned on the hot tap but lacked the strength to twist it off, succumbing to third-degree burns, then a heart attack. My brilliant, beloved father boiled to death in the bath, surrounded by his own shedding skin.

A few hours later—21 months sober—I cleaned up what looked like a crime scene, climbed into the same bath and buried my head in my knees. He had wanted his body to be left to medical science, but it had been destroyed inside and out. Later, at the inquest—his five children plus a former patient shouting that he had been a “wonderful man”—the coroner made clear that my father had been conscious when he endured his injuries; removing our final hope that death had preceded them.

So, no, drinking yourself to death is not a “bloody good way to go”; not fun, not cool. It cleaves me to tell this story. I feel as if I’ve betrayed the person I loved most. But I’ve violated my father’s privacy because privacy is what keeps us drunk; the public fronts we put on to conceal the private horror. His body couldn’t be put to medical use, but his story might.

And still everyone longs for that happy ending. When they learn that I’m sober, people say, “And do you feel amazing?” I don’t, and doubt I ever will. I sleep better, and one feels one has a lot more time at first. But there’s been no “pink cloud” (the AA term for a phase of early sobriety characterized by elation), no sudden rush of energy in which I Marie Kondo my entire life. However, I’m no longer inflicting misery on myself and others, and that will have to suffice. Nor am I in any way evangelical about sober life. If you can drink sanely, drink sanely, and raise a glass on my behalf. If you can’t, I’m sorry, and will help as much as I can.

A decade into abstinence, I felt not triumphant but weary, raw as a cut thumb. That’s still about the sum of it.

Hannah Betts is a writer at The Times of London. Her Substack is hannahbetts.substack.com