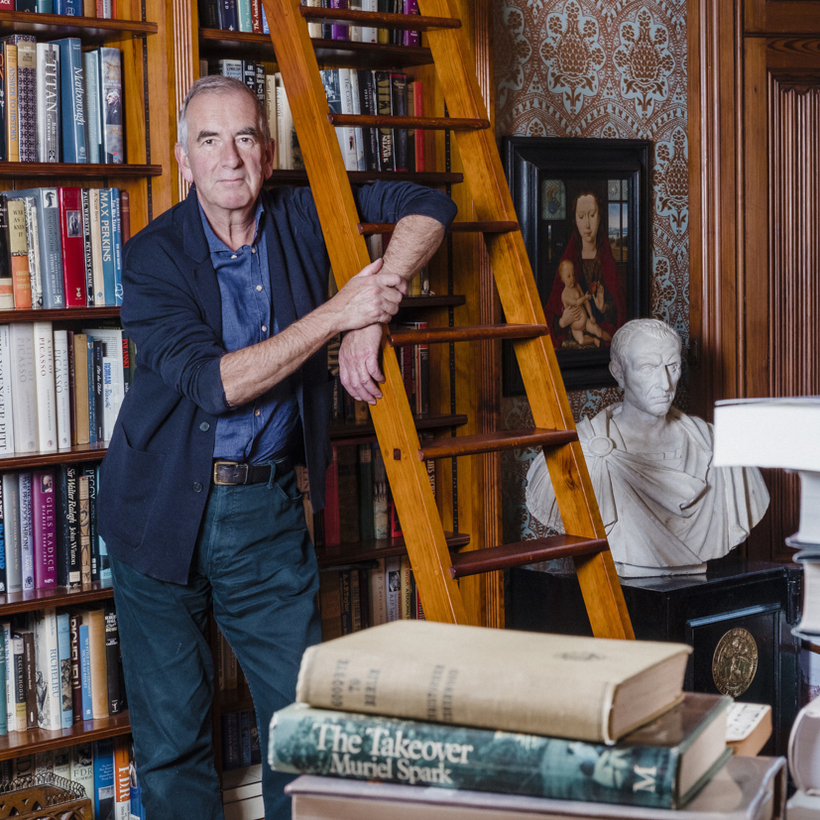

O lucky man! Robert Harris lives in one of the most enviable houses I know, a vast Victorian vicarage in Berkshire with beautiful lawns running down to the Kennet & Avon Canal. And his study is a sort of cathedral to writing, completely lined with bookshelves, with a brass lectern, a bust of Cicero (three of his novels are about Cicero) and a portrait of Joseph Conrad, another hero.

His books are all immaculate hardbacks, alphabetically arranged from Ambler and Amis to Wodehouse and Woolf. Consequently he can lay his hand on any book he wants in a minute and rarely needs to visit libraries for his research. Doesn’t he have any shabby paperbacks? Yes, he says, ‘We have readable books! Gill and I never throw a book away. But they’re all upstairs.’

His wife Gill Hornby, sister of the more famous Nick, is also a novelist but she doesn’t have a grand study: she writes at her laptop in the sitting room. She started late – only 10 years ago – but she has already published four novels – The Hive, All Together Now, Miss Austen and Godmersham Park – to consistently good reviews.

They met when they were both working on Newsnight, married in 1988 and had four children – the great project of their lives, he tells me – but now the children are grown up and he and Gill are rattling round the empty nest. ‘Nothing prepares you for it, it’s so sad.’ Their eldest child is a publisher, one works in business, another for charity and their youngest is just finishing a degree in composition at Guildhall.

They moved to the vicarage exactly 30 years ago when Robert’s first novel, Fatherland, suddenly made them rich. He was working as a journalist (political editor of The Observer, then columnist for The Sunday Times) but he also had a commission to write a biography of John le Carré. He started work on it, and did an interview with le Carré’s first wife (which nobody else has ever done), but then le Carré seemingly got cold feet and decreed that he could not publish anything till after his death. So Harris was left with no immediate work and decided to try his hand at writing a novel himself.

The result was Fatherland, imagining a future in which the Nazis had won the war. He sent a few chapters to his American agent, heard nothing for a fortnight, but was then told that 12 publishers were competing for it, and ‘That was the end of normal life really! The American rights went through the roof, hardback about half a million, I think, and paperback more than a million. So we moved to the country in 1993 and lived happily ever after.’

He bought himself an open-top Aston Martin but, tragically, he has now sold it because he says a 60-something man looks stupid in a convertible – he has an enormous Range Rover instead. And from then on he was able to devote himself to living in the country and writing novels, which had always been his dream.

Harris grew up in a council house in Nottingham, and still retains his Midlands accent. His father was a printer and on Saturdays used to take the boy Robert to the printing works where he loved the clank of the machinery and the smell of the ink. He did well at school, and won a scholarship to Cambridge, where he edited Varsity and was president of the Cambridge Union.

Then he joined the BBC, working mainly for Panorama and Newsnight, and making lifelong friends such as Jeremy Paxman, Peter Mandelson, and Jon Snow. Their party performance singing “YMCA” as Village People is still fondly remembered. He wrote a book with Paxman about chemical warfare. He also wrote a gripping book, Selling Hitler, about the Hitler Diaries, which is being republished this year for the 40th anniversary of the hoax.

Twelve publishers were competing for it, and “That was the end of normal life really!”

He says that most of his friends are still journalists, either from Fleet Street or the BBC, and ‘I find them much more congenial company than anyone else’. He prefers them to novelists who, he once told Tatler, were ‘pretentious, jealous, treacherous, back-stabbing’, though he is friends with Sebastian Faulks. And, of course, he is also friends with politicians. George Osborne, Danny Finkelstein, and Andrew Mitchell are regular guests at his parties, and Peter Mandelson is godfather to one of his children.

He was always keen on politics. He wrote a school essay when he was six entitled ‘Why me and my dad don’t like Sir Alec Douglas-Home’. His father was a lifelong Labour supporter and Harris was too until Jeremy Corbyn came along – now he supports the Lib Dems. ‘Though I’d have no problem voting for Starmer. I think he’s done a remarkable job in rescuing the Labour Party. But I’m not partisan between them and the Lib Dems. I’ll support whoever is the candidate with the best chance of beating the Conservatives.’

He spotted Tony Blair as a rising talent in the Labour Party early on and wrote a favorable piece about him in The Observer. In the run-up to the 1997 general election, Blair invited Harris to accompany him all round the country. ‘I think those two or three weeks I spent with Blair on the campaign trail gave me an insight into power and politics, the masks that are put on, the performance, the deal, that will last me all my life. And I think power is more or less the same in any era or in any country – so when I came to write The Cicero Trilogy I could translate it all to the Roman world.’

Harris later fell out with Blair, chiefly over the invasion of Iraq (and in 2014 he called him ‘a narcissist with a messiah complex who lives a tragic life’), but he used his knowledge of Blair to inform The Ghost, his brilliant thriller about a ghostwriter who is hired to write the autobiography of an ex–prime minister, and discovers that the previous ghostwriter was murdered. He was supposed to be writing the second book of his Cicero trilogy when Blair resigned in 2007 and he asked his publishers if he could pause Cicero and write The Ghost instead and they said, great, do it. So he went out to Martha’s Vineyard (where it is set) to do the research and wrote it in three months.

But, meanwhile, he had a call from Roman Polanski (despite his 1978 conviction not then perceived as the pariah he is today) who said he wanted to make a film of his fourth novel Pompeii and would he write the screenplay? So he went to Paris to work on the screenplay with Polanski but the production company could never raise the finance, so he went back to writing The Ghost. When it was finished he sent it to Polanski and said, ‘Maybe we should make this instead – no volcanoes, no togas!’ And Polanski rang about 10 days later and said, great, let’s do it. ‘Things aren’t supposed to work out so easily but they did.’

Apparently Tony Blair was annoyed by his book and told a mutual friend, ‘Next time tell him to stick to the past.’ But Cherie Blair was delighted with the film The Ghost Writer (they changed the name as there was already a film called The Ghost) because, she told Olivia Williams (who played her character), she got to sleep with Pierce Brosnan and Ewan McGregor!

Several of his novels – Fatherland, Enigma, Archangel, An Officer and a Spy, Munich: The Edge of War – have been made into films and the next one will be Conclave, based on his 2016 novel about all the cardinals locked in the Vatican to elect the next Pope. It stars Ralph Fiennes and is directed by Edward Berger, who recently won an Oscar for All Quiet on the Western Front. Harris went to Rome for a day to watch the filming and was impressed. ‘They were filming the conclave itself and they’d got a brilliant mock-up of the Sistine Chapel and 115 extras dressed as cardinals and it was great. But it’s bizarre that it’s being made, given that it’s all men.’

Actually, most of his novels are mainly about men – he rarely writes women characters. Why? ‘I think it’s because I’m drawn to writing about power and politics in the past and women weren’t often to the fore. But I would very much like to write a novel with a woman as the central character, and in fact that might be my next book.’ Could it be Venetia Stanley? I noticed that he had several books about her on his desk and he confirmed that yes, it could. ‘Her relationship with Prime Minister Asquith was riveting.’

“Things aren’t supposed to work out so easily but they did.”

Asquith was obsessed with her and would write to her sometimes three times a day even when he was in Cabinet meetings, so she had great political influence. But they probably never slept together, which is fine by Harris, because he famously doesn’t write sex scenes. ‘I think it’s almost impossible, just awkward and embarrassing. Romantic love is not my thing. My territory is ambition, power, politics and I don’t think there’s any harm in writers doing what they feel they can do best. But I would like to write more about a woman.’

Harris doesn’t have to deliver his next book till next summer, and probably won’t start writing it till January. He loves the research phase, reading letters and memoirs, visiting all the locations. Researching Pompeii was wonderful, he says, because it meant spending weeks on the Bay of Naples. ‘I do an enormous amount of research – my research notes are always much longer than the finished book – and I won’t use all of it but it gives you confidence and I think the reader senses that you’re not skating on thin ice. Also, in an odd way, the more you know, the more confident you are about leaving things out. I hate historical novels where you get all the research.’

When he starts writing, he aims to produce 800 words a day, working all morning from eight till lunchtime, seven days a week. He sends each chapter to his editor when it is finished so it can go out to the translators – his novels are published in 40 languages. In the afternoon he walks the dog and forgets about work. ‘I have no hobbies – I don’t play golf or anything like that.’ Gill is musical and plays the piano but ‘I’m tone-deaf, I can’t sing. I can’t do anything apart from writing.’

He reads very little contemporary fiction, but goes back to old favorites such as Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Conrad, Orwell and le Carré. His children told him to read Sally Rooney so he did but with no obvious enthusiasm – ‘It felt like dispatches from the modern world’. He is particularly scathing about writing that comes out of creative writing courses. ‘There’s something wrong with it, it always feels dead. It’s made to be read aloud to eight or nine people who all share your ideas. There’s far more energy in genre writing because it’s written to be read.’

He is particularly keen on le Carré and considers Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy ‘a masterpiece’. He spent a lot of time with le Carré, staying with him in Cornwall, when he was supposed to be writing his biography. ‘And I think if you were to say which novelist has had the most influence on, certainly male, writers, including me, I would say le Carré. But he was a very tricky character. He played games with people. He had a colossal ego, almost the biggest ego of anyone I ever met, more than a politician or an actor. And when I found out about all the women, I just found it rather tacky and was happy to bow out. [Le Carré had countless affairs throughout both his marriages]. But I might use him in a novel one day.’

I asked if Harris had ever had a bad review, and he said, yes, plenty – The New York Times panned all his novels, even An Officer and a Spy (about the Dreyfus affair), which he considers his best. ‘But I’ve dished out plenty of bad reviews in my time so I’m not going to whine when I get some back.’ And he is not bothered by the idea of ‘sensitivity readers’ – ‘I’ve never written about pert breasts’ – but thinks, on the contrary, they could be valuable. ‘When I think of things that were said casually when I was at school or university about other races, or about women – I don’t think stopping that is censorship, I think it’s just decency, actually.’

Robert Harris pretty much personifies decency. He always looks slightly old-fashioned, in his tweed jackets and highly polished brown brogues, and enjoys playing up his old-buffer image. When he orders coffee in the pub he asks for, ‘What I’ve been taught to call a flat white.’

Romantic love is not my thing.

And he is becoming more conservative in old age. He used to be a republican but then he had a conversation with Eric Hobsbawm, the Marxist historian, shortly before he died and Hobsbawm said the best countries in the world to live in were constitutional monarchies because they seemed to give the best guarantee of freedom, and he was convinced. He watched the Coronation with great pleasure. He met the King, then Prince Charles, 20 years ago when he came to the royal premiere of Enigma and then invited him and Gill to a weekend at Sandringham. Harris sends him each new novel on publication and always gets an appreciative reply. The King’s father, Prince Philip, was a real fan and was once photographed on a train reading one of his Cicero books.

Harris still follows politics eagerly and considers it ‘the essence of life, the most incredible theater of characters, drama, incident, unexpected events, human frailties, astonishing courage. The whole business, the cavalcade, fascinates me all the time.’ But he thinks the caliber of politicians has diminished. ‘Roy Jenkins was one of my closest friends towards the end of his life and there are no politicians like him anymore, or Denis Healey or Carrington.

Now it’s just this rather dreary professional political class.’ He was appalled when Boris Johnson won the general election. He already knew Boris, who had once interviewed him for The Telegraph, and then tried to get him to write for The Spectator, and, ‘I always quite liked him. He was amiable but shambolic – always late on deadlines. But the thought that he might become Prime Minister! I mean, I’d rather have one of our cats!’

Was he never tempted to go into politics himself? ‘No. I’m interested in power and politics and I know politicians, but I’m interested in observing them rather than doing it myself. I think by temperament I’m an observer and I don’t really like giving orders or bossing people about. To go and do the daily round of politics would be deadly for me. I’m not very good with bores and I’m hopeless with faces and names – I once introduced Gill as Elizabeth! And I am a writer naturally and always wanted to be. At eight, nine, 10, I was inventing fake newspapers and I’ve always just wanted to earn my living by writing. The best thing is to go into my study in the morning and stay there and put words together.’

This summer, he will emerge from his study to go to the Borders for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction – his latest book Act of Oblivion is nominated – and he will do a book event at Hampton Court but he is not keen on publicity. He rarely gives interviews because he thinks the books should be the star, not the author. He believes that fame, the sort of fame that means being recognized in the street, is quite destructive for writers. ‘Because you should really just live very quietly, in your head. What’s that Flaubert quote? “Be regular and orderly in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” As a writer, and as a journalist, it’s better to be unobserved, to be the person in the corner taking notes. I watch rather than wish to be watched.’

I asked which character in his novels was the nearest to a self-portrait and he said, ‘Oh that’s a very good question. I tend to write about people who are on the sidelines, eg private secretaries, ghostwriters. I thought when I wrote the novels about Cicero that they had nothing to do with me, but a friend said, “Don’t you see these books are all about you? They’re about an ambitious provincial outsider who has no trick other than words.”’

At 66, he’s aware of aging and believes, ‘There is nothing good about it’ but he doesn’t follow any fitness regime. ‘I drink more than I should. I allow myself one cigar a day. I avoid medical checkups. I think the moment I started to diet or give up alcohol I’d drop dead.’ He will certainly never retire. ‘I don’t have a pension but I’ll carry on working till I drop. Gill calls me a sociable hermit and I think that’s right. I like meeting people but I’m also very happy in the house on my own. Also I think that my entire life, when I look back on it, has been a quest not to have a boss, to get up in the morning and do what I want to do.’ Which of course is what he’s achieved. O lucky man!

Lynn Barber is a U.K.-based journalist and five-time British Press Award winner. She is also the author of An Education