There have been plenty of films about fashion — The Devil Wears Prada, Prêt-à-Porter, The September Issue and, OK, Zoolander — but there is none in which the main character is a shoe. Air, released this week, tells the story of the creation of the Nike Air Jordan. Even if that name means nothing to you, don’t cross this movie off your watchlist because it’s about more than just a shoe. It’s about how one product transformed sports marketing, made Nike the world’s biggest sporting goods firm, and determined much of what we all wear today.

Before the Air Jordan there were only two trainers anyone had heard of: Adidas Stan Smiths and Converse All Stars. You wore them on weekends and on holiday, never to the office. Air Jordans changed that. They helped to make sneakers the shoe of choice for everyone — sports stars, fashionistas, celebrities, even world leaders. Rishi Sunak wears white Common Projects trainers (about $405) in Whitehall, while Barack Obama prefers Stan Smiths.

The Air Jordan also kick-started the streetwear revolution, paving the way for brands including Stüssy, Supreme, Kith and Palace and tempting the grands maisons of fashion to sign up street stars as chief designers. Even the arch-traditionalist Louis Vuitton appointed Virgil Abloh artistic director and, after his recent death, replaced him this year with the rapper and producer Pharrell Williams.

How did all this happen? It almost didn’t, as the film shows. In the 1980s Nike wasn’t the Just Do It giant it is today. It sold running shoes to professional athletes and keep-fit joggers. It would have stayed that way had it not been for Sonny Vaccaro, played by Affleck’s long-time film bro Matt Damon. He had been trying to develop Nike’s basketball division for years, but kept being outbid by its US rival, Converse, and Adidas, the German sportswear outfit that dominated world sport then.

With Nike’s boss, Phil Knight, played by Affleck, threatening to pull out of basketball, Vaccaro does what any US sports star would do: he goes for a Hail Mary. Instead of dividing up his $250,000 sponsorship budget — a fortune at the time — among three or four promising basketball players, he decides to wager the lot on one youngster who is about to start his first full season for the Chicago Bulls. The trouble is, Michael Jordan is set to sign with Adidas. The only way to persuade him to — maybe — switch sides is risky: convincing his key adviser, his mother, Deloris, to bring her son to Nike’s headquarters in Oregon and offer him the kind of shoe that no one has ever created before.

The Air Jordan kick-started the streetwear revolution.

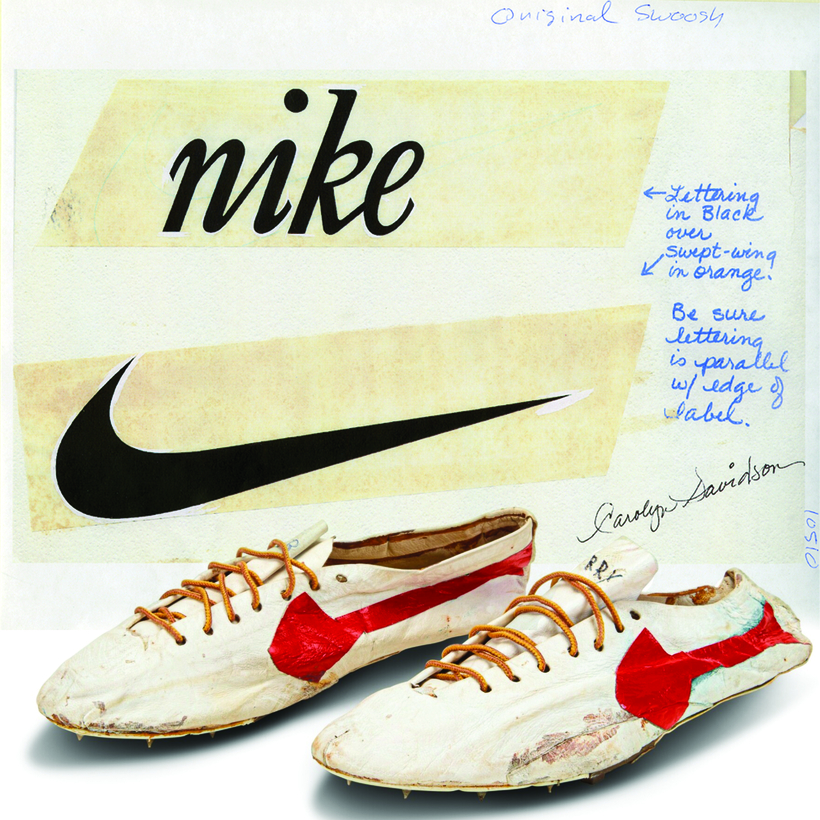

The Air Jordan 1, developed in 1984, was the first to be named after and devoted to a living athlete at the start of his career. As Vaccaro puts it: “Michael does not wear the shoe. He is the shoe and the shoe is him.” It was also the first to have its own unique logo (a silhouette of Jordan flying through the air); the first to break the rules of its sport (the US National Basketball Association stipulates that shoes should be mainly white and Nike promised to pay Jordan’s NBA-imposed $5,000 fine every time he stepped on court in the red and black numbers); and the first to pay royalties to the athlete on the sale of every pair. This package, which has become commonplace for sports stars, persuaded Jordan to dump the Germans. Knight thought the shoes would generate a few million dollars a year. In fact, the Jordan collection has come to generate 10 per cent of Nike’s overall revenue with sales topping $5.1 billion a year, helping it to overtake Adidas.

Hip-hop artists, who were driving popular culture, quickly picked up on the value of personal and subversive shoes. Run DMC even wrote a song about their beloved Adidas shell toes. It was only a matter of time before fashion designers followed. Walk down the chic streets of any leading city and you’ll see trainers in the shop windows selling at up to $1,200 a pair — with lower-priced models lining the shelves at JD Sports and Size. We’re all sneakerheads now.

So influential have trainers become, they are now collectibles. In 2020 a pair of autographed match-worn Airs from Jordan’s rookie season fetched $560,000 in an online auction at Sotheby’s. The overall sneaker resale market could reach $30 billion in global sales by 2030, the investment bank Cowen & Co predicts. “Sneakers are an emerging asset class that transcends generations and demographics. School kids and fortysomething hedge fund traders all want the same pairs of Jordans,” says Rob Franks, a co-founder of the UK retailer Kick Game.

Nike promised to pay Jordan’s NBA-imposed $5,000 fine every time he stepped on court in the red and black numbers.

Yet getting Air greenlit was not straightforward. The idea of two of Hollywood’s leading white men making a film about the greatest African-American sports star is a tricky sell. Luckily, Affleck, who directed the film, played a regular card game with Jordan in Los Angeles and got his blessing — on one condition: “Viola Davis is gonna play my momma.” How did Affleck persuade Davis? “By begging,” he joked to The Hollywood Reporter. Deloris turns out to be the heroine of the story, not just because she sees that Nike can offer her son a better shoe, but also because she insists he is paid the royalties that have made him a multibillionaire.

Affleck’s wife, Jennifer Lopez, was a key adviser on the movie. He praises her as “incredibly knowledgeable about the way fashion evolves through the culture as a confluence of music, sports, entertainment and dance.” She has also helped to capture the 1980s, largely through its terrible clothes (beige slacks in the office and neon shell suits on weekends), its vile cars (Knight drives an electric lilac Porsche) and an epic soundtrack that runs from Chaka Khan to the Clash via Squeeze.

The only duff note is perhaps unavoidable. Jordan is there, but you see only his silhouette, and occasionally you hear his voice or, rather, that of the man “playing” him. As Affleck explained at a press conference: “I thought the minute I turn the camera on somebody and ask the audience to believe that person was Michael Jordan, the whole movie falls apart.” Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the film is that Jordan was not paid a penny by Affleck and his production team. But then, after the licensing deal of the century, he scarcely needs the cash.

Air, directed by Ben Affleck, and starring Viola Davis and Matt Damon, is in theaters now

John Arlidge covers business for The Times of London. He is also a Fellow of the Orwell Prize for Journalism