Army colonel John Ohmer Jr. was the sort of visionary who peers into the future, sees danger, then goes around warning everyone—only to have his warnings fall on deaf ears. It’s a tragic character type. Not until later—after the dam breaks, or the enemy attacks, or the planet burns—does everyone realize they should have listened.

An amateur magician, engineer, and veteran of World War I, Ohmer’s job for the army was to devise camouflaging and deception techniques. In 1940, before the U.S. officially entered World War II, he was visiting the U.K. to observe how the British used camouflage when he suddenly realized the U.S.’s vulnerability to a domestic attack.

In Southern California, where Ohmer was stationed, Los Angeles was particularly vulnerable. An early aviation center due to its pristine year-round flying weather, the city was home to many of the nation’s biggest aircraft manufacturers—including Douglas, Hughes, Lockheed, and Northrop—which were already building warplanes for European allies.

This concentration of expertise and infrastructure—located perilously close to the coastline—was a ripe target for military juggernauts like the Japanese or Germans. In the first major war where airpower played such an essential role, the loss of just one of these plants could lengthen the conflict considerably.

The answer, according to the man in charge of camouflage technology, was more camouflage. Ohmer was particularly impressed by the British military’s use of camouflage to fool the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain, lasting from July until October 1940. By disguising military installations and building decoy towns and airfields, the British had tricked the Germans into dropping their bombs miles away from actual population centers and military sites. Hundreds, if not thousands, of lives had been saved, not to mention the physical property protected.

Due to its pristine year-round flying weather, Los Angeles was home to many of the nation’s biggest aircraft manufacturers, including Douglas, Hughes, Lockheed, and Northrop.

Upon returning to the U.S., Ohmer, then a major, began proselytizing for the increased use of camouflage, urging his military superiors to do more. He believed that multiple targets, including Wheeler Field, the air base near Pearl Harbor, were vulnerable to attacks from a Japanese military that was already seizing other assets in the Pacific and expanding its area of control toward Hawaii. Ohmer even drew up a specific plan for disguising Wheeler.

But Ohmer’s bosses weren’t convinced it was worth the effort. They thought that the estimated cost of disguising the Hawaiian air base, $56,210, was too high.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor and other nearby sites; Wheeler alone lost 83 planes, each one costing roughly the same as Ohmer’s camouflaging proposal. Fate had just converted him into that most unfortunate sort of prophet: the doomsayer who is proven right. Before this moment, an isolationist America had been oblivious—almost willfully so—to the world collapsing around it. Now, the country was forced to accept the dark reality.

Realizing it had been an error to ignore Ohmer, the army corrected course by placing him in charge of one of the most ambitious camouflaging operations in history, and one of the more curious assignments of World War II. From Seattle to San Diego, vulnerable assets would need disguising, including airfields, oil depots, factories, air-defense stations, and military bases.

Fortunately, Ohmer had a secret weapon right in his backyard: Hollywood.

Operation Hollywood

After Pearl Harbor, March Field in Riverside County, California, about 60 miles east of Los Angeles, looked more like a movie set than the U.S. Army Air Corps base it actually was. Here, Ohmer brought set designers, animators, art directors, landscape artists, carpenters, lighting experts, and prop designers from the Hollywood studios, including Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Disney, 20th Century Fox, Paramount, Universal Pictures, and Warner Bros. Among the bustle of military aircraft and training drills, these entertainment-industry professionals designed and built the sort of props they had created for many blockbusters.

Not only did these artisans know how to work fast and under pressure, but their experience with building movie sets also helped them understand the fundamentals of illusion—of making the eye see something it actually doesn’t. Ohmer’s “draftees” included the architect and Academy Award–nominated set designer John Detlie (who was married to Veronica Lake); the art director Gabriel Scognamillo, who had worked with such greats as Jean Renoir, William Wellman, and Ernst Lubitsch; and the up-and-comer Harry Horner, who later did production design on classics such as Born Yesterday, The Hustler, and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

The recent attack in Hawaii wasn’t the only thing motivating Ohmer’s crew to work fast. Less than three weeks after that disaster, a Japanese submarine—I-17, a fully loaded warship that housed a reconnaissance airplane in the forward section of its deck—was spotted off the coast near Salem, Oregon. On February 23, it resurfaced off the coast of Santa Barbara and fired upon Ellwood Oil Field, an oil storage facility located near Goleta Beach. During the next two weeks, it sank two American cargo ships sailing in waters between San Francisco and Cape Mendocino.

The physical damage from the Ellwood attack was minimal, but significant psychologically. Throughout the Pacific states, talk of another domestic attack dominated conversations and headlines as the Japanese captured Manila, Hong Kong, and Singapore in a time span of barely two months. Facing the grim reality before them, Americans set to work preparing.

Much of Ohmer’s camouflaging work elaborated on ideas pioneered several months earlier at a Douglas bomber factory in Santa Monica, located on the site of what is today the Santa Monica Municipal Airport and Museum of Flying (which was then commonly referred to as Clover Field).

With a prescience similar to Ohmer’s, the aviation pioneer and mogul Donald Douglas Sr. had also anticipated an enemy attack on American soil and ordered his chief engineer and test pilot, Frank Collbohm, and a renowned architect, H. Roy Kelley, to investigate ways to camouflage the plant at the Santa Monica Airport. (Collbohm later co-founded the Rand Corporation and hired Kelley, who helped popularize ranch-style homes in the West, to design its headquarters.)

Their initial efforts, working in collaboration with set designers from Warner Bros., laid the foundation for what would eventually become Ohmer’s most ambitious efforts to disguise nearly three dozen other sites along the coast.

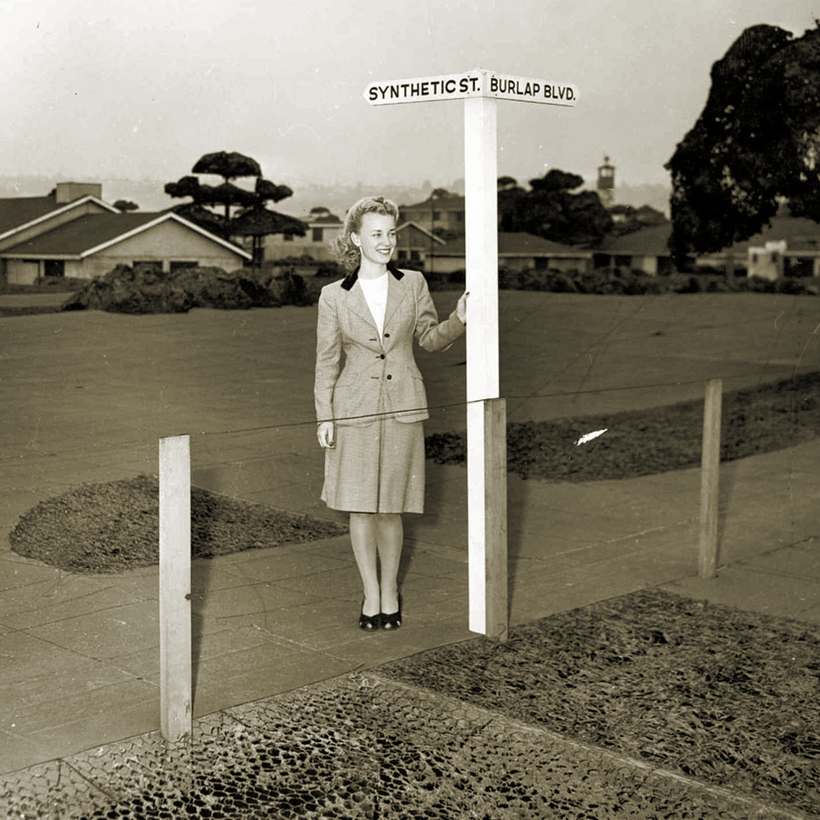

The illusion of a suburb was achieved by erecting 400 poles among the facility’s various terminals, hangars, and parking lots, then attaching to them a canopy made of nearly five million square feet of chicken wire and netting. Atop this mesh-like covering sat lightweight wooden models of suburban homes, including attached garages, fences, and clotheslines complete with laundry swaying in the pleasant California breeze. Next to these homes sat “trees” made of twisted wire and chicken feathers painted to look like leaves, which apparently smelled horrible whenever it rained.

To integrate this fake neighborhood with the surrounding town, the canopy was painted with streets and sidewalks that blended in seamlessly with the real-world streets and sidewalks located nearby. The plant’s runway—a dead giveaway to enemy aircraft—was painted green to look like a field of grass.

Once the camouflaging was complete, the effect was so convincing that pilots had difficulty finding Clover Field and were forced to land elsewhere instead. To aid other confused pilots, Douglas stationed men on the runway and told them to wave red flags whenever planes were scheduled to land.

From the ground, the Douglas plant looked exactly like what it was: a factory churning out bombers. From the air, though, it resembled something entirely different: a leafy American suburb that could have been a set from Leave It to Beaver. The disguise wasn’t foolproof, but the camouflage artists understood that the illusion didn’t need to be perfect; it just needed to be good enough. According to Douglas Airview, the company’s magazine, “This would give defending planes and guns their chance. In the bookkeeping of war, that possibility is worth any cost.”

Ohmer’s camouflaging efforts at other air bases were even more ambitious.

At a Boeing plant in Seattle, artists from Warner Bros. concocted paint pigments designed to confuse enemy infra-red photography.

At Burbank’s Lockheed Air Terminal (currently Bob Hope Airport), a canopy similar to the one used by Douglas featured decoy automobiles made from rubber, as well as a section resembling a small farm, including animals, a barn, and a silo. This pleasant façade was made as realistic as possible by painting random patches of fake grass brown because, well, not everyone has the time to keep their lawn pristine.

To give the neighborhood a sense of life and enhance the overall effect of the disguise, Lockheed workers would regularly climb atop the canopy and stroll around on reinforced catwalks located under the fake sidewalks. Occasionally they’d move the decoy cars around, mimicking people coming and going from work, and swap out the laundry on the fake clotheslines. Fake fire hydrants hid vents that helped circulate the air beneath the canopies and keep the factory workers comfortable.

The Hollywood artisans’ experience with building movie sets helped them understand the fundamentals of illusion—of making the eye see something it actually doesn’t.

This close attention to detail might seem excessive—would enemy bombers flying thousands of feet overhead actually notice if the laundry hadn’t changed?—but is understandable when you consider the anxiety of that moment in history. If the Lockheed factory burned, the military would lose the approximately 3,500 bombers, fighters, and cargo planes it produced yearly—output that would easily take a year to restore. As added insurance against such a loss, Ohmer’s unit created a decoy air base in a distant empty field to divert the enemy’s attention. It featured dummy aircraft and fake runways made by burning long stretches of grass.

Ohmer tested his camouflaging by taking an army general on a reconnaissance flight and asking him to locate the Lockheed facility. From 5,000 feet—lower than a typical bombing run—all the general could see was an endless expanse of suburban sprawl. Ohmer’s deception was so effective, in fact, that the nearby Warner Bros. studio was forced to camouflage its lot because it feared that the soundstages—which resembled hangars—might be accidentally targeted by enemy bombers instead.

Once Ohmer had his camouflaging in place, the only thing left to do was wait and see if it worked on enemy bombardiers. Perhaps they had uncannily sharp vision, or maybe some spy had tipped them off to the deception? American war workers had to live with the anxiety of not knowing, keeping their heads down and trusting the protection of flimsy chicken wire and decoy houses. The suburban mirages hovering above them, a jerry-rigged imagining of the American Dream, would hopefully keep them safe.

Fortunately, the enemy bombers never came. It’s reasonably certain they would have if they had ever gotten the chance, but they were never able to advance so close to the U.S. again. In June 1942, the Japanese Navy suffered an enormous defeat at the Battle of Midway, forcing it to abandon its plan to take control of the Pacific. Over the next three years, as the war progressed and U.S. forces advanced, the chances of a large-scale attack on the West Coast diminished. Even so, some sort of smaller attack—perhaps another stealth submarine—couldn’t be ruled out.

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, U.S. general Douglas MacArthur claimed in August 1942 that the army’s camouflaging techniques were causing the Japanese military to waste valuable ammunition on decoy sites while actual military assets were left unharmed. In a way, this vindicated Ohmer’s previous warnings from before the war, the ones made when the U.S. was still complacent about the threats it faced. Fortunately, though, he was eventually heard.

Today a new threat is found in the Pacific, in the form of rising sea temperatures and a great floating island of plastic. Again, it’s worth remembering that sometimes the Cassandras are worth listening to.

Reid Mitenbuler is the author of Wild Minds: The Artists and Rivalries That Inspired the Golden Age of Animation and the new book Wanderlust: An Eccentric Explorer, an Epic Journey, a Lost Age. You can read his essays on the making of these books here and here