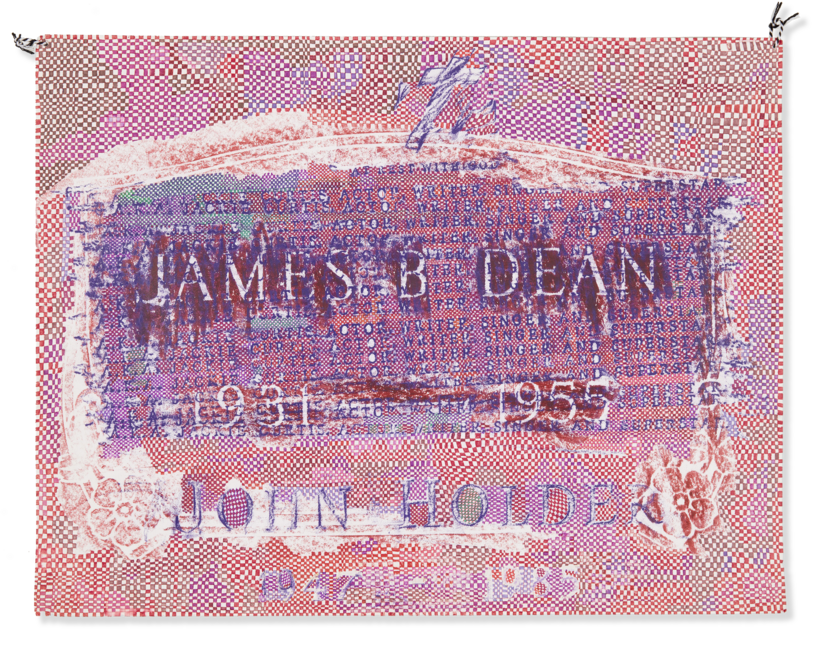

Over the last 40 years, the 68-year-old American artist Scott Covert has traversed cemeteries around the world, eluding groundskeepers while adding to his collection of gravestone rubbings: names as disparate as Elsa Schiaparelli, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Lyman Frank Baum, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Truman Capote, not to mention some of the world’s most notorious murderers and mourned victims (for example, the Clutter family, of Kansas).

Covert’s method is simple. On a piece of paper, with oil-wax crayons, he etches the numbers and letters he finds on headstones and markers. Some he does delicately; others get more pressure. Later, Covert collages these transcriptions in drawings and oil paintings, creating disembodied realms of intermingled souls and ghostly celebrity. A single work can take weeks or years. The energy is complex and powerful.

Covert was born in 1954 in Edison, New Jersey, and got to New York about the time Warhol’s downtown scene was heating up. In the late 70s he became the first male usher on Broadway—“I saw Evita hundreds of times,” he says—and was also part of the scene at Club 57 on St. Marks Place, where he co-founded Playhouse 57 with Andy Rees. Theater led to the fine arts and Covert’s funereal beat. With an exhibition of his rubbings opening at the London-based gallery Studio Voltaire on January 25, his first solo presentation outside the U.S., AIR MAIL catches up with the artist.

ELENA CLAVARINO: You first made grave rubbings with your sixth-grade class in Edison, New Jersey.

SCOTT COVERT: When I was a kid, there was a Colonial cemetery right next to my school. And it was before they protected them. So we would go there and grave-rub.

E.C.: At that age, what captivated you about it?

S.C.: Just that I was making things and having a good time. I did this thing that I wanted to do—numbers. I wasn’t thinking about names. I went very high with the numbers. I still do that once in a while.

E.C.: So it wasn’t about being fascinated by the idea of death?

S.C.: The idea of death was part of it. I guess it never scared me. When my grandfather died, my mother said, “This is what happens; you’ll be safe.” I see the positive no matter what.

E.C.: You received a scholarship to the San Francisco Art Institute but instead went to New York to act. What brought you back to art?

S.C.: I liked the idea of being in theater, but I hated memorizing lines.

E.C.: Your artistic breakthrough came in 1985, when you did the tombstone of Florence Ballard, one of the founding members of the Supremes.

S.C.: A gallery in South Africa wanted to give me a show, and it was during apartheid. So I thought, Well, I’ll just do rubbings of great Black people. I went to Florence Ballard’s grave—her name’s Chapman; she was married—and I did it once, and it slipped. So I took another color and did it again. And I heard the bell that Gertrude Stein talks about—“Oh, this is it!”

E.C.: Why does a work take so long to finish?

S.C.: I love abstract painting. And Pop art. What’s more important in American art than those two schools, right? I didn’t want squishy, squashy rich kid putting oil paint on a canvas. I wanted each brushstroke to be a lifetime.

E.C.: What does a grave mean to you?

S.C.: Well, it’s the end and it’s the beginning, because that’s where the people are forever.

E.C.: And how do you pick colors?

S.C.: It’s random, really. But I will go to brighter, lighter colors because I want to get rid of the sadness, if there’s sadness there.

E.C.: So you try to counter the negative?

S.C.: Yeah. That’s why I always try to do murdered people with comedians. I hope it breaks up the horrible time that the person must have gone through.

E.C.: Does it get lonely being on the road, going to cemeteries?

S.C.: I’m an old man now. When I was young, I met a lot of people. Now I’m just very happy to do my work and not worry about a thing. I feel close to these people, whose graves I rub.

“C’est la Vie” will be on at Studio Voltaire, in London, beginning January 25

Elena Clavarino is the Senior Editor for AIR MAIL