Immediacy is the hopping-off point of William Klein’s photography. His most memorable photographs aren’t images frozen in time but impromptu moments captured at near boil, their bustling activity crowding the frame.

A punk kid points a gun barrel at the camera with one eye cocked like a pint-size desperado. A young woman in a bikini leans forward, flashing a wide smile of happy teeth, while in the background slumps a dapper gentleman in the mild throes of dyspepsia. His group shots often present a thick stew of sullen faces, like a gathering of dark clouds.

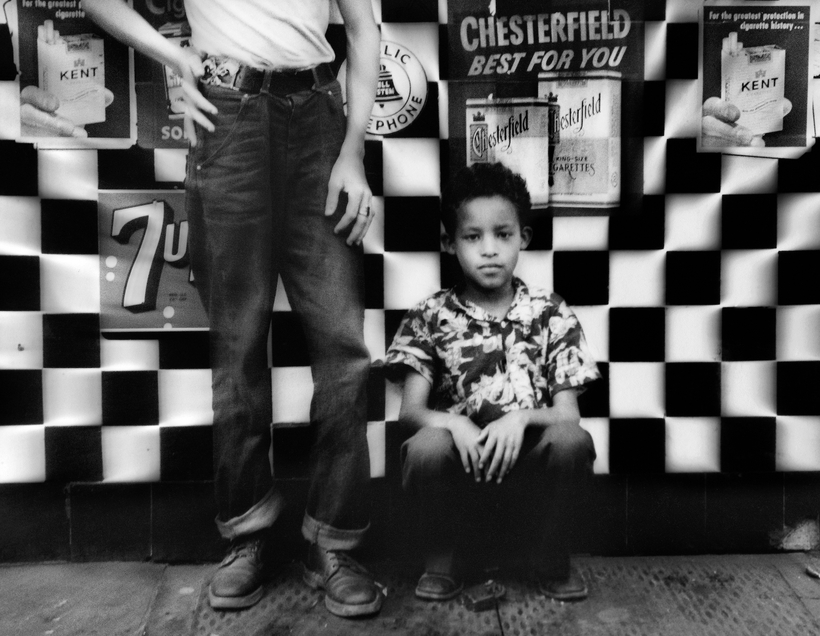

Klein’s early reliance on a 35mm camera, high-contrast film, a wide lens, and nimble footwork produced pictures with a tabloid flare, their graininess, dynamic blur, and inky shadows hitting like pepper spray. Like many photographers of the postwar era, he has a natural propensity for noir, savoring the sizzling reflections of movie-marquee lights on car hoods and wet pavements, the jumpy collage effect of billboard advertising.

But it would be a mistake to categorize Klein as a social realist and roving shutterbug, dishing out slices of life on the fly. Spanning decades and containing multitudes, his work is multi-dimensional, incorporating different media and versatile lines of attack, infused with formalist rigor, critical acuity, and a knack for juxtaposition that could be playful but never cute.

“A great Klein photo is a snatched marvel of formal organization but it never lets you forget it is a physical encounter. A kiss or slap. At best, both.” So writes David Campany, the curator of the International Center of Photography’s megillah exhibition “William Klein: YES. Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013,” the first major retrospective of Klein’s achievement in decades. Prepare to be kissed, slapped, and perhaps even tickled.

Multitudinous Beginnings

Born in 1928 to Jewish Hungarian immigrants, Klein grew up in an Irish neighborhood that sounded more brass-knuckle than lace-curtain. He was aware early in life that anti-Semitism was right around the corner and ready to rumble. His refuge was the Museum of Modern Art and all the wonders it held.

Enlisting in the army when he was 18, Klein served in Germany during W.W. II and later enrolled at the Sorbonne, studying painting under Fernand Léger, many of whose works suggested cubistic playing cards or the innards of mechanical beasts.

It was Alexander Liberman, the dapper wizard of Condé Nast (his official title, editorial director, didn’t do justice to his Diaghilev gifts), who spotted the promise in Klein and hired him as a staff photographer.

For Vogue, Klein extricated models out of the studio and planted them in the streets, at crosswalks, and in storefronts, contrasting their formal poise and folded-umbrella silhouettes with the jostle and jumble of civilians going about their day. His adventurous use of color gave off heat and humor, reminiscent of Ernst Haas’s rich, sheeny palette. (One shot featured a model in a raspberry coat extending a white-gloved hand to hail a taxi, cutting a soignée figure in a traffic hell.)

The grunge and off-kilter compositions didn’t always please the patrician tastes of glossy-magazine sensibility. Klein’s first photo collection, Life Is Good & Good for You in New York (one of the all-time top book titles), consisted of photographs that had been rejected by Vogue for being too vulgar and déclassé.

Their loss. Life Is Good & Good for You in New York was a breakthrough success, hugely influential, and spawned three successors devoted to the everyday-capital spectacles of Rome, Moscow, and Tokyo—the Klein Quartet, one might call them, if one were being highfalutin.

Klein has also proved himself to be an influential path cutter as a moviemaker. The biting critiques of commerce and celebrity strewn through his photographs ballooned into full-on satire in feature-length films such as Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), a picaresque pop spoof of fashion modeling and instant celebrity. And The Model Couple (1977), about a pair of nondescript nabobs chosen to live in a model apartment rigged with cameras for 24-7 surveillance, anticipates Albert Brooks’s Real Life, The Truman Show, and similar mock vérité.

As a documentary director, Klein displayed his versatility with unconventional studies of Muhammad Ali, Little Richard, Eldridge Cleaver, the French Open of 1981 (with its racquet-wielding clash of titans John McEnroe and Björn Borg), and the trance-inducing semiotics of Times Square neon signs (Broadway by Light, viewable on YouTube).

If his films aren’t as prominently known as his photographs, it may be because with pictures it’s easier to keep track of the bull’s-eyes. Flip through the pages of any William Klein photo book and it’s bam, bam, bam.

“William Klein: YES. Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013” opens on June 3 at the International Center of Photography, in New York

James Wolcott is a Columnist for AIR MAIL. He is the author of several books, including the memoir Lucking Out and Critical Mass, a collection of his essays and reviews