The Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide emits a snort of derision when I mention the dreaded words “magical realism.” She blames Surrealism’s so-called pope, André Breton, for starting a trend in the West during the 1930s that led to the work of Latin American artists being characterized in this way. “Mexico is not a magical country,” Iturbide, 79, tells me on a video call from her home, in Mexico City. “It is full of wonders, but I think the French and the Americans love to pigeonhole us or give us labels.”

Iturbide, who last year became the first Latin American woman to win Sony’s Outstanding Contribution to Photography Award, insists that everything she photographs is “the reality” of what she sees—no more and no less. Her secret? “I really need a sense of surprise for me to take a successful photograph,” she says. A measure of her eagle eye can be taken in an exhibition opening next weekend at the Fondation Cartier, in Paris, which gathers more than 200 images from her 52 years of taking photos.

Most of the pictures in “Heliotropo 37,” named after the street number of her studio, in Mexico City, are in black and white, and all are shot with film using a handheld camera and without a telephoto lens, tripod, or flash. “In a way, I really see the world in black and white,” she says, “as if I was taking an abstract view.” The exceptions are a series of color photographs, taken by Iturbide especially for the exhibition, of massive pink-and-white blocks of alabaster and onyx being mined and cut in the Mexican village of Tecali de Herrera.

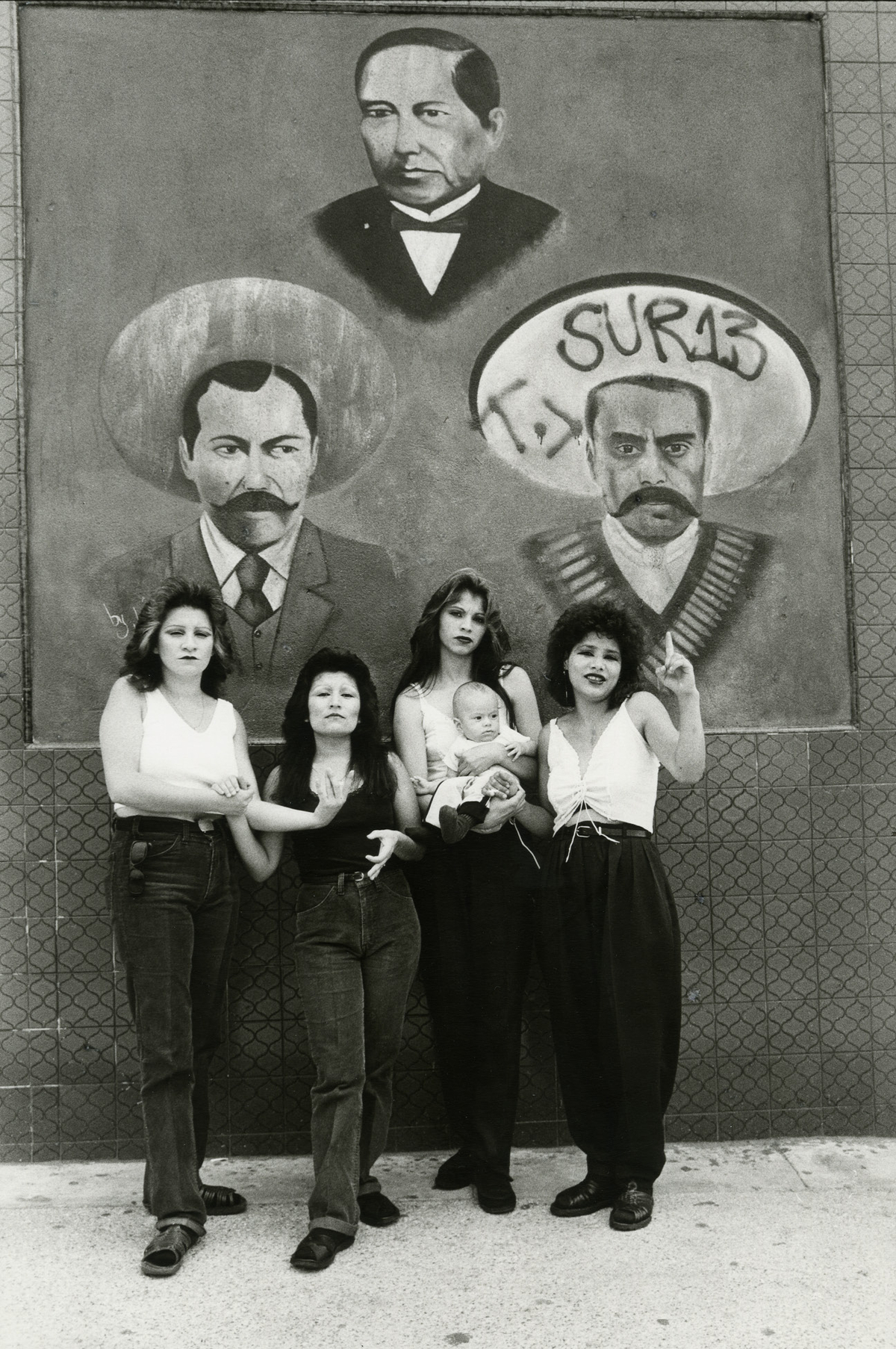

Iturbide is best known for her black-and-white portraits of Mexico’s indigenous communities, in which she often focuses on traditional rituals and ceremonies. In the 1980s, she became the first photographer to take pictures of a “rapto,” whereby a young Zapotec woman elopes with her future husband to his house and makes love for the first time. Her 1986 photograph The Abduction, included in the exhibition, depicts a young woman lying on a bed strewn with traditional flowers and confetti.

“I don’t know why I love these rituals so much. Maybe it has to do with my Catholic education,” says Iturbide. “But I love all these little angels and images of death—all of those things that people believe in or play with.”

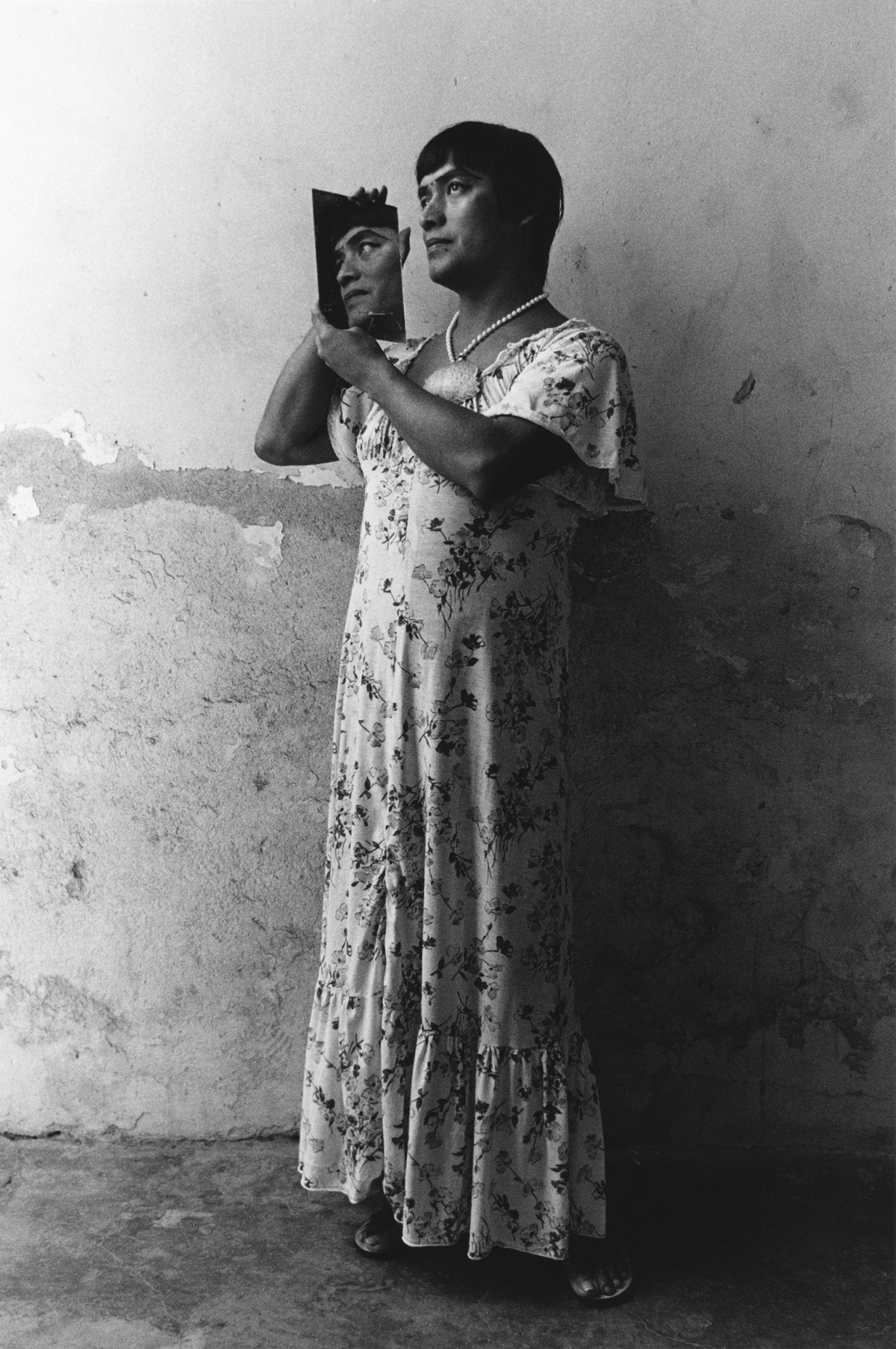

Like many of Iturbide’s pictures from around that time, The Abduction was taken in the town of Juchitán de Zaragoza, in southern Mexico. Iturbide continues to appreciate Juchitán de Zaragoza as “a place where eroticism flows in a very natural way.” She has enormous affection for the women of the town, who have driven its market economy for centuries. One of her most well-known photographs is Our Lady of the Iguanas (1979), which depicts a powerful Zapotec woman with a crown of live iguanas on her head.

The image is one of several by Iturbide to have taken on a life of its own, inspiring numerous murals and clay figures, and even featuring as a feminist icon in the 1996 Hollywood film Female Perversions. Another is Mother Angel (1979). Its representation of a caped Seri Indian woman, carrying a tape recorder, was used by Rage Against the Machine for the cover of their politically charged single “Vietnow.”

Iturbide welcomes the idea of these images’ “flying away” like the flocks of birds she has made a custom of photographing. But she also stresses that her original motivation for taking them has nothing to do with the way they are now frequently interpreted. “I am a feminist, but my work is not feminist,” she says. “I am very much involved in politics, but my work is not political.” —Tobias Grey

“Graciela Iturbide: Heliotropo 37” opens at the Fondation Cartier, in Paris, on February 12

Tobias Grey is a Gloucestershire, U.K.–based writer and critic, focused on art, film, and books