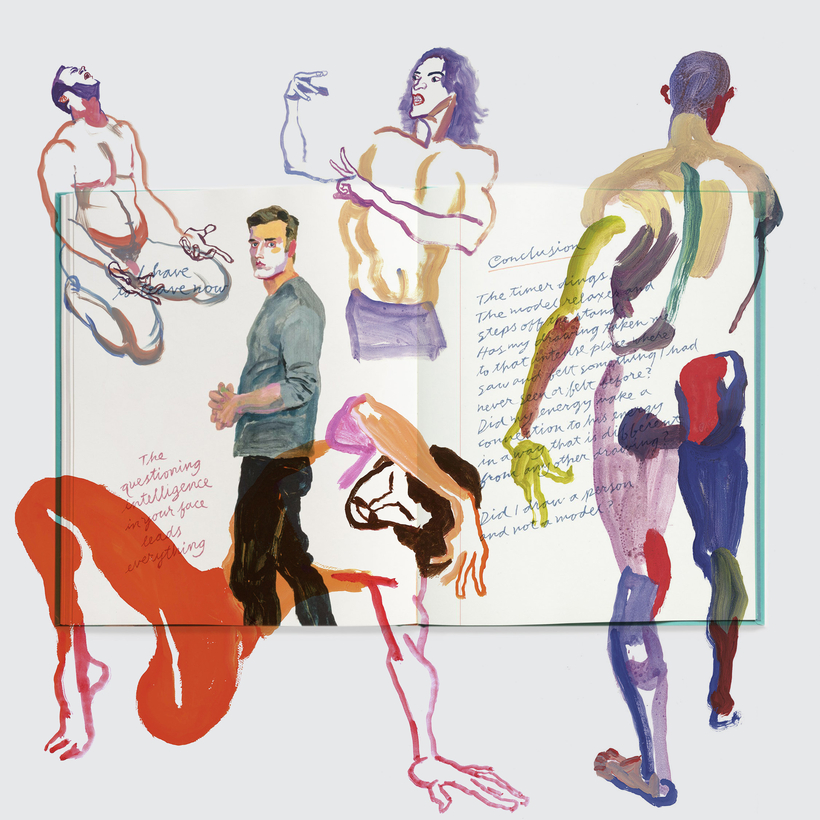

James McMullan, the celebrated artist, illustrator, and poster designer, has a lovely, funny, and poignant new book: Hello World: The Body Speaks in the Drawings of Men. The book features beautiful paintings of nude men and the artist’s reflections on what the painting process was like and what the attitudes of these men were. To celebrate the publication of the book, the Bienvenu Steinberg & J gallery, in New York, will host an exhibition of these paintings opening on November 17.

Fans of McMullan’s who know him chiefly through his posters for Lincoln Center Theater will be amazed at this new collection—not only by the paintings themselves but by McMullan’s often hilarious commentaries about what he is thinking as he paints. For example: for the nude man who says, “Everything is going to my hips,” the artist muses, “I paint a big stroke around your belly feeling like a Nascar driver.” For the “just slightly annoyed” man, the artist says, “Eyebrows and fist say it all!” This is a new world for the artist and a great departure from his previous work.

If Lincoln Center Theater has a “brand,” then that brand has been created as much by McMullan’s posters as by our work. He has painted 91 of our plays, starting in 1986, and each one manages to express its creator’s interpretation of the play and perfectly represent the author’s intention.

McMullan manages to capture le moment précis of each play, and he does it well in advance of ever having seen the production. Even more astounding: his paintings manage to look like the production way before there is a production! How is that possible? Some strange psychic power is at work here.

This phenomenon has occasionally manifested itself in the form of the director stealing the moment caught in McMullan’s poster and putting it onstage. Daniel Sullivan, for instance, put the artist’s tortured embrace of his easel into Ten Unknowns (2001). A few years earlier, in 1995, Nicholas Hytner put the Carousel poster pose into the musical’s ballet, and Gerald Gutierrez put McMullan’s heroine gazing out the window into The Heiress.

Another of McMullan’s skills lies in his versatility and willingness to change. In 2015, we were producing The King and I, and there was much debate about whether Mrs. Anna or the King should appear on the poster, or both.

McMullan first painted a lovely, delicate moment in which Mrs. Anna leans over the railing of a ship and takes in the glories of Bangkok as she sails into the harbor. Too lovely, too delicate, we said. Try something more brutal. McMullan then painted the King in a scary and Yul Brynnerish pose. Too ferocious, we said. He then hit on a moment when Mrs. Anna, filled with wonder and fear, enters the giant gates of the palace for the first time. Bingo!, we said.

Of course, any of the three would have worked, but we chose the one in which McMullan decided to mix beauty and brutality. He had listened to us very carefully.

Two important and often overlooked, or taken for granted, characteristics of McMullan’s art are his glorious, bold, surprising use of color and his lettering. Who could imagine that wallpaper could ever be such a shade of green, or a king’s robe would be plum-colored, or that a piazza would be so vibrantly yellow? He finds shades of colors that are rarely seen anywhere. And his title treatments! Somehow, the lettering always suits the painting—and the play.

James McMullan is a great artist, an intelligent thinker, an appreciative listener, a persuasive arguer. His contribution to Lincoln Center Theater has been extraordinary; the publication of his new book and the simultaneous exhibition is proof that he continues to grow and dazzle.

Hello World: The Body Speaks in the Drawings of Men, by James McMullan, is out now from Pointed Leaf Press

An accompanying exhibition of paintings from Hello World opens at the Bienvenu Steinberg & J gallery, in New York, on November 17

André Bishop is the producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater