After reading Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Killers” in March 1927, the 44-year-old artist Edward Hopper was moved to write to the editor of Scribner’s Magazine. “It is refreshing,” he said, “to come upon such an honest piece of work in an American magazine after wading through the vast sea of sugar-coated mush that makes up the most of our fiction.”

There is no sugar or mush about Hopper. He takes his coffee black and he drinks it late at night. We know him as the artist of diners and deserted curbs, roadside stops and hats pulled low. His paintings inspired Alfred Hitchcock. The set for the Bates Motel in Psycho (1960) was based on Hopper’s House by the Railroad (1925). Very austere it is, too. Once you start thinking of Hitchcock you can’t help but see Rear Window (1954) in Hopper’s views of fire escapes and flats. One of Hopper’s favorite films was Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), with its shadows, silhouettes and echoing Viennese streets. You can see the mark of Hopper in the sets for Sin City (2005) and every ill-lit Batman film.

In a new documentary, Hopper: An American Love Story, released to coincide with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York, the Hopper scholar Carol Troyen talks of the “powerful emotional emptiness” of his paintings. Only Hopper could paint Sun in an Empty Room (1963) and fill it with pathos. It is every house move, every end-of-term pack-up, every heart-wrenching clearance after a death. Unlike some BBC arts documentaries that can’t show a painting for more than three seconds for fear of boring the viewer, here the camera lingers and allows you to look.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York, on the Hudson River, in 1882. His father was a well-to-do dry-goods merchant; his mother encouraged her son to draw. Hopper filled page after page with thumbnail sketches of local boats, trains and men on newfangled bicycles. He grew up to paint the America of the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. In early works it is the America of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). Not the Jazz Age parties of Long Island, but the gas stations of George and Myrtle, and New York City’s all-hour bars. Later it is the America of Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, published in 1961 but set in the 1950s: secretaries, filing cabinets, commuter trains and suburban ennui.

Hopper’s diner striplights shine just as brightly today, nearly 60 years after the artist’s death, at the age of 84, in 1967. Compare his Nighthawks (1942) with another “iconic” American painting, Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930). Fewer and fewer of us identify with the long-faced man and woman, and their pitchfork. Farming life was hardscrabble then and the great-grandchildren have long left the family farm. Hopper’s nighthawks haven’t gone away. Three generations on and they are still there, at single desks in WeWork offices, on treadmills at 24hr PureGyms, slurping noodle soup in ramen bars. The hawks had their hats, we have our headphones. If I had the knack of Photoshop I’d show how easy it would be to replace the books and coffee cups of Hopper’s sitters with smartphones. Scrolling the nights away.

You can see the mark of Hopper in the sets for Sin City (2005) and every ill-lit Batman film.

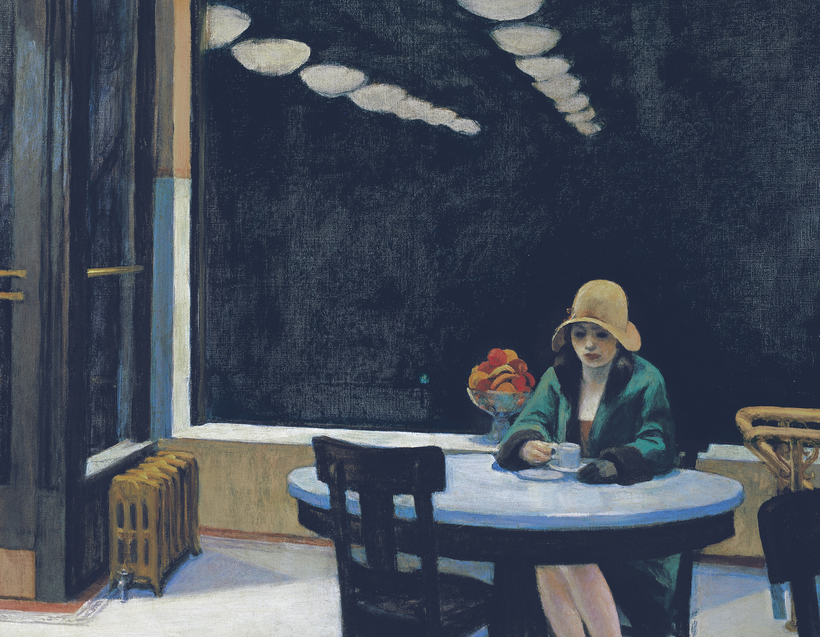

One of his most famous paintings is Automat (1927). A woman sits alone at a table, staring at not very much. The automat was at that time a newish invention. You dropped a nickel in a slot and out came a sandwich, a potpie or a mac ’n’ cheese. Hopper would have made fine paintings of self-service checkouts in all-night Tescos or the strange anonymous aisles of Amazon Fresh. No interaction, no connection, no need for a friendly cashier. Just scan your goods and go. Lockdown made Hopper seem all the more prescient. I lost count of the number of pandemic essays and think pieces illustrated by Hopper’s Morning Sun (1952). A woman in a pink slip stares out of a window. Bare legs, bare walls, bed made but not slept in. Social isolation in a single city room.

The documentary reminds us to look for the light in Hopper as well as the darkness. When he was a boy in Nyack his eye had been caught by the effects of the sun on a nearby building. “There is a sort of elation,” he remembered, “about sunlight on the upper part of the house.” From a young age, Hopper didn’t fit. To begin with, he was too tall. In high school he was already 6ft 4in, and bullied for his height. He spoke in a monotone “slower than the proverbial molasses”, the art critic Forbes Watson said, and looked “like a professor of higher mathematics in an out-of-town college”.

He studied art by correspondence course, then, in the early 1900s, at the New York School of Art and Design. He was never part of the Ashcan School, which painted scenes of everyday life in the poorer parts of New York, or of the American Scene, which sought to capture the Depression of the 1930s, or of Symbolism, Surrealism or photorealism. He hated to have labels “pinned on me”. He thought the American Scene painters “caricatured” the US.

Hopper had no definite calling. He was not strictly a portrait painter, nor a still-life painter (although the lives he paints are often very still), nor a painter of the great outdoors. “Well,” he said when asked. “I like buildings. And I like people, somewhat. I like landscapes, somewhat.” Somewhat is the word. Reticence, uncertainty, the sigh not the shout. There is tension, but rarely drama, in his paintings. He complained in his youth, when working as a “rotten illustrator” to make ends meet, that magazine editors wanted busy scenes with people waving their arms and “grimacing and posturing”. (There wasn’t an artist in America, he said, who hadn’t been driven by the Depression to take on commercial work or to “teach, paint signs, shovel coal or something”.)

Hopper would have made fine paintings of self-service checkouts in all-night Tescos or the strange anonymous aisles of Amazon Fresh.

The woman in Automat could hardly be stiller. Should she stay or should she go? She’ll stay for want of a motive to move. Hopper knew the syndrome he so often painted. The illustrator Walter Tittle remembered the young Hopper “suffering from long periods of unconquerable inertia, sitting for days at a time before his easel in helpless unhappiness, unable to raise a hand to break the spell”.

Hopper was partial to paintings by Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. You can trace a line from Automat to Manet’s Plum Brandy (c 1877), with its slouching sitter in pink, or to Degas’ dejected L’Absinthe (1875-76). Hopper had reason to feel dejected as a student in Paris. He made three trips to Europe between 1906 and 1910 and, for the better part of ten years, held a torch for the capricious, prickly Alta Hilsdale, whom he may have met in France. He pined, he pestered, she married someone else. One improbable academic theory has it that the fragile female figure in Summer Interior (1909), naked from the waist down, is Hopper, traumatized by sexual rejection. This is given short shrift in the documentary.

The love story of the title refers to the US and to Hopper’s partnership with his wife, Josephine Nivison. They met as art students, then again in Brooklyn in 1923. He quoted poetry by Paul Verlaine, she quoted the next lines in French. Nivison became his painting companion, his wife and his model. She cured him of the Alta affair.

Nivison was his spur and his champion. They married in 1924. He hadn’t sold a picture in a decade before she started promoting his art, and had no real success or recognition until he was 44. Nivison posed for almost all his female figures, rather ending the idea of Hopper as voyeur or Peeping Tom. Can it be peeping when it’s your own willing wife?

Some of Hopper’s most arresting scenes are unpeopled. Take Drug Store (1927). It must be late if even the drugstores are closed. The lights are still on. They lend the green and red pharmaceutical bottles an almost alchemical glow. In Nighthawks and Automat Hopper gives most of the composition to vast panes of plate glass. As the nights draw in, think how you would paint a dark city window, black and transparent, at once revealing the inside and reflecting the out. Where would you even begin? In another Hemingway short story, A Clean, Well-lighted Place (1933), a waiter says: “I am one of those who like to stay late at the café. With all those who do not want to go to bed. With all those who need a light for the night.”

The documentary points out the oddness of some of Hopper’s scenes. The Nighthawks café has no apparent outside door. The window in Automat reflects a line of pendant lights, but no other tables, chairs or punters. Hopper’s angles are off. He always tells it slant.

Nivison kept a diary that revealed her husband’s methods. She watched in awe as he worked at Office at Night (1940), in which she played the slinky secretary part. “Each day,” she wrote, “I don’t see how E. can add another stroke … each day he goes right on & this picture becomes more palpable — not fussy … reduced to essentials … so realized.” It could be a still from Mad Men, but Hopper always resisted stories and interpretations. “I hope,” he said of this painting, “it will not tell any obvious anecdote, for none is intended.”

There’s one thing we get wrong again and again about Hopper: solitary is not always sad. We never say Vermeer’s women at windows are lonely. Rapt, pensive or reflective, but not lonely. We ought to envy Hopper’s blue-suited woman in Compartment C, Car 293 (1938) with two seats to herself, and books and magazines to hasten the journey. It is dusk. The blinds are half-lowered. If no importuning man appears — exception might be made for Cary Grant — she may get around to her novel.

Sometimes, then as now, a person wants to be alone with their thoughts. No company, no chatter, no iPhone. Hopper understood that in the right circumstances, whether in compartment C or at a café counter, solitude meant not despair, but discovery. “The inner life of a human being,” he wrote, “is a vast and varied realm.”

Hopper: An American Love Story is playing now in cinemas in the U.S. and the U.K.

Laura Freeman is a U.K.-based book-and-art critic and the author of The Reading Cure: How Books Restored My Appetite