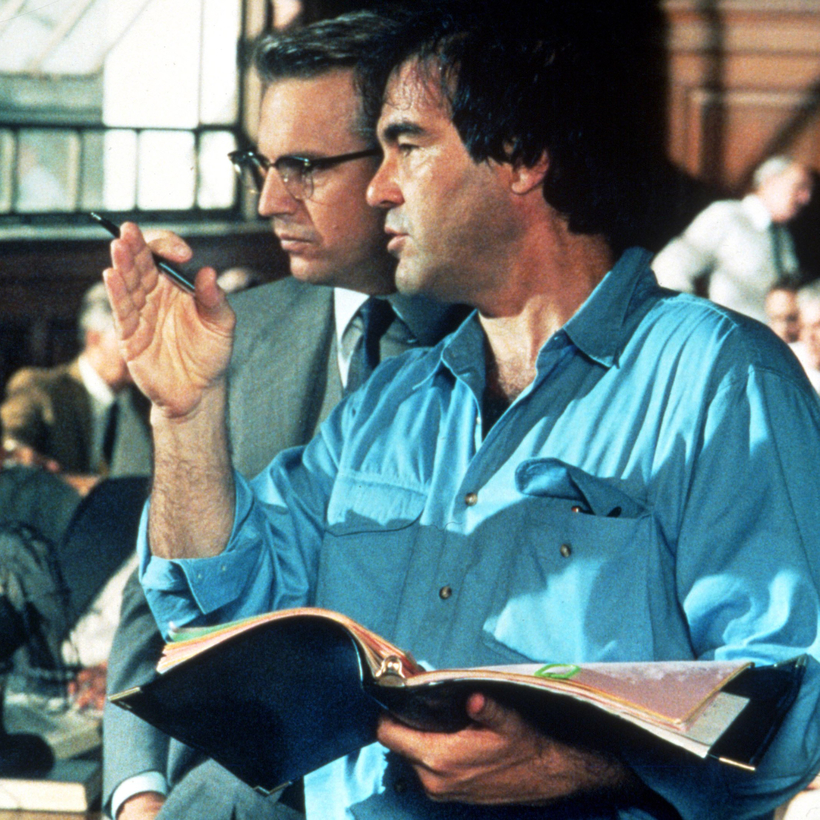

In his star-studded, mesmerizing 1991 film JFK, Oliver Stone endorsed New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison’s theory of the Kennedy assassination. It’s a complex web implicating the C.I.A., the F.B.I., the military-industrial complex, and anti-Castro Cuban exiles, but it relies heavily on the purported guilt of one man, the only person to be criminally prosecuted for the crime: Clay Shaw. In his recent Showtime documentary, JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass, Stone once again makes the case for Shaw’s culpability. But this time the director leaves out its most lurid element, one that played a prominent role in JFK but which now, 30 years later, seems dated, or worse.

A highly decorated veteran of the Second World War, a published playwright, and a successful international businessman, Shaw helped found the New Orleans International Trade Mart and was renowned for restoring landmark properties in the city’s historic French Quarter. Far from being a critic of the 35th president, let alone party to a conspiracy aimed at murdering him, Shaw was a member of the official reception committee for Kennedy’s 1962 visit to New Orleans.

Physically striking at six-foot, two-inches tall, with a shock of white hair, the confirmed bachelor, who counted Gore Vidal and Tennessee Williams among his wide circle of acquaintances, was a highly desirable escort—or “walker”—for prominent society women. And as these details suggest, Shaw was discreetly gay, a fact that today may strike us as irrelevant but which assumed an awesome place in the fevered imagination of Jim Garrison, and that of his latter-day acolyte Oliver Stone.

On March 1, 1967, Garrison arrested Shaw for conspiring to kill Kennedy. Lee Harvey Oswald, whom the Warren Commission had determined to be the sole assassin, was born in New Orleans, and his presence there for several months before the tragedy in Dallas piqued the interest of the publicity-hungry prosecutor.

According to Garrison, Shaw was the elusive “Clay Bertrand,” whose name surfaced during the Warren Commission’s investigation after an eccentric New Orleans lawyer named Dean Andrews claimed that Bertrand had called him the day after the assassination to ask if he would defend Oswald. Bertrand was the “queen bee” of the New Orleans homosexual underworld, Andrews said, and had previously sent Oswald and some “gay Mexicanos” in need of legal advice to his office.

Andrews had been in the hospital and under heavy sedation when he supposedly received this call, however, and he later told the F.B.I. that Bertrand was “a figment of my imagination.” In persisting to claim otherwise, Andrews said in his testimony at Shaw’s 1969 trial, he had been “carrying on a farce.”

“Farce” aptly characterizes Garrison’s prosecutorial effort against Shaw, which seemed to attract every flake, con man, and grifter in the Big Easy.

Take his star witness, an insurance salesman named Perry Russo. Under various states of hypnosis and narcotic inducement, Russo told investigators about a party he attended where Shaw, Oswald, and a former airline pilot fired for homosexuality named David Ferrie discussed their plans to kill the president.

Asked by one of Shaw’s defense attorneys, Irvin Dymond, during cross-examination why he had not immediately gone to the authorities with this information, Russo nonchalantly replied that he “had an involvement with school, which was more pressing to me.” Russo also claimed to have witnessed Shaw amid the crowd during Kennedy’s 1962 visit to New Orleans, where Shaw was sporting tight pants, “like a lot of queers in the French Quarter wear,” and cruising young men.

The testimony of a second supposed witness to Shaw’s murderous scheming was undermined by his admission that he regularly fingerprinted his daughter because “enemies” often impersonated his relatives in their efforts to destroy him. Yet another prosecution witness came to the courtroom dressed in a toga and claiming to be the reincarnation of Julius Caesar.

Ultimately, the jury spent less than an hour in deliberations before acquitting Shaw. (It would have taken even less time, one juror confessed, had he and his peers not “all had to queue up and pee before we got down to business.”) Garrison was widely condemned for committing gross prosecutorial misconduct; according to The New York Times, the trial constituted “one of the most disgraceful chapters in the history of American jurisprudence.” Shaw, who died in 1974 at the age of 60, was the victim of a vicious character assassination.

You would not know anything about Garrison’s disreputable behavior from watching JFK, however, which turned reality on its head by casting the reckless prosecutor as a hero (“a Jimmy Stewart character in an old Capra movie,” according to Stone) and the innocent man he persecuted as a villain. JFK Revisited recycles the same lies.

Shaw was discreetly gay, a fact that today may strike us as irrelevant but which assumed an awesome place in the fevered imagination of Jim Garrison, and that of his latter-day acolyte Oliver Stone.

“We now have evidence and 12 people who confirm that Shaw used [Bertrand] as an alias,” one of the documentary’s two narrators, Whoopi Goldberg, states. (The other narrator is Donald Sutherland, who memorably played mysterious ex-Pentagon official “X” in JFK.) But as Fred Litwin, the author of an indispensable book about the Garrison prosecution, On the Trail of Delusion, has meticulously demonstrated, each and every one of these 12 claims is false. JFK Revisited also states that Shaw was arrested “on charges that he was part of the conspiracy to kill President Kennedy” while neglecting to mention that he was acquitted.

The most egregious lie about Shaw that Stone advances in JFK Revisited is that he was “a highly valued contract agent” of the C.I.A. with “covert security clearance.” From 1948 to 1956, Shaw was one of 150,000 Americans who volunteered information about their travels abroad “on a non-clandestine basis” to the C.I.A.’s Domestic Contact Division. This was the extent of his involvement with the agency. As the historian Max Holland has written, the claim that the C.I.A. played a role in the Kennedy assassination through its “agent” Clay Shaw—which Garrison promoted, JFK popularized, JFK Revisited reproduces, and a majority of Americans believe—is almost certainly a K.G.B. fabrication.

First aired by a Communist-aligned Italian newspaper, Paese Sera, on March 4, 1967, three days after Shaw’s arrest, the charge that Shaw was a C.I.A. “agent” was picked up (and embellished) over the next several weeks by leftist and Communist newspapers around the world. It was dezinformatsiya—disinformation—of the sort that the Russians had been honing since long before the Cold War even began and would deploy masterfully during the 2016 presidential election.

Shaw harbored another secret that intrigued Stone. From the very beginning of Garrison’s investigation, homosexuality assumed an outsize role. A group of “high-status fags,” he told reporters, was responsible for the assassination. The first person against whom Garrison announced conspiracy charges, David Ferrie, was, like Shaw, gay. This, the district attorney believed, was more than mere coincidence. “Clay Bertrand,” he asserted without evidence, was the alias Shaw used in New Orleans gay society, and homosexuality was the means by which the conspiracy to kill the president could be understood.

Oswald was “a switch-hitter who couldn’t satisfy his wife,” Garrison said, and the Dallas nightclub owner who shot and killed him, Jack Ruby, was a homosexual whose “nickname was Pinkie.” (No evidence has ever emerged that Oswald or Ruby was anything other than heterosexual, though Marina Oswald did complain about her sex life.)

As for these men’s motive? “John Kennedy was everything that Dave Ferrie was not—a successful, handsome, popular, wealthy, virile man,” Garrison said. “You can just picture the charge Ferrie got out of plotting his death.” Shaw, notwithstanding his own good looks, also wanted to kill “the world’s most handsome man.” It was “a homosexual thrill-killing” akin to the infamous 1924 Leopold and Loeb case, wherein a pair of young male lovers killed a 14-year-old boy in hopes of committing “the perfect crime.”

In August 1968, one of Garrison’s investigators wrote a cover story for Confidential, a scandal magazine that pioneered the practice of outing closeted gay people. Kennedy was the “victim of a sick and vicious homosexual plot,” author Joel Palmer wrote. “Two shocking parallels tie the various suspected plotters together at every turn: overt homosexuality and frustrated attempts to liberate Cuba, culminating in the Bay of Pigs affair.” Oswald was “a $20 trick” who shaved his pubic hair “to present the illusion of puberty” for his johns.

A group of “high-status fags,” Garrison told reporters, was responsible for the assassination, which he described as “a homosexual thrill-killing.”

Palmer further posited that “President Kennedy represented the father to these men and Cuba the mother. When the President aborted the Cuban invasion by not supporting it as these men thought he should, he became a wife beater, the mother beater, all the ugly things a child finds to rebel against in a father no longer needed.” The right-wing homosexuals acted out their Oedipal feelings, therefore, by assassinating the president. According to Garrison, Oswald’s professed Communist sympathies, his passing out leaflets on behalf of the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee on the streets of New Orleans, were a cover story. Shaw, the theory went, had delegated him as the “patsy” because he was jealous that Oswald had stolen his boyfriend, Ferrie.

These ramblings seem crazy today. But remember that, at the time they were expressed, homosexuality was illegal in almost every state; in Louisiana, those found guilty of the “crime against nature” could be sentenced to five years’ hard labor. Despite his social prominence, Clay Shaw could not afford to be open about his sexual orientation, a vulnerability Garrison was keen to exploit.

“The only way to fundamentally understand Garrison’s prosecution of Shaw is by understanding the ways in which men who had sex with men were legally defined, socially constructed, intensively policed, and culturally pathologized in the United States in the decades following World War II,” writes Alecia P. Long, author of Cruising for Conspirators: How a New Orleans DA Prosecuted the Kennedy Assassination as a Sex Crime, a new book about the role of homosexuality in the Shaw case. “If Americans had not believed that sexual deviance made people inherently suspicious and that homosexuals were likely to commit all manner of crimes, Garrison’s case would have been much harder to undertake and then prosecute.”

Aside from references to Shaw’s “peculiar gait” and “tight pants,” and Russo’s testimony about his cruising young men in the crowd during Kennedy’s visit to New Orleans, the prosecution avoided the issue of homosexuality at the trial. Stone lacked such inhibitions, putting the motif of “high-status fags” front and center in JFK.

Tommy Lee Jones portrays Shaw as an epicene rogue, campy and menacing. The scene in which this sinister homosexual is interrogated about his decadent lifestyle and murderous activities is interspersed with images of Kevin Costner as Garrison at home with his wife and children. When the police come to arrest Shaw at his palatial French Quarter mansion, he appears at the front door wearing a silk bathrobe, cigarette holder daintily in hand.

In one scene, a gay prostitute named Willie O’Keefe, played by Kevin Bacon, tells Garrison about a party he supposedly attended where Oswald (Gary Oldman), Ferrie (Joe Pesci), and Shaw planned the assassination with a group of anti-Castro Cubans. Like much else in the film, the O’Keefe character is fiction, a composite of Perry Russo and three gay men who told Garrison that Ferrie had introduced them to Shaw yet whom Garrison judged not sufficiently credible to withstand cross-examination. (One of many examples illustrating how Stone’s threshold for accuracy is even lower than that of his truth-challenged hero.)

Another scene, emanating entirely from Stone’s perverted imagination, depicts a sadomasochistic Mardi Gras orgy where Ferrie, Shaw, O’Keefe, and a second male prostitute dress up in costumes and watch stag films. As O’Keefe, outfitted as Marie Antoinette, pleasures himself in the background, Ferrie, dressed as an 18th-century French fop, leads Shaw, a gold-paint-encrusted Hermes (the Greek god of trade), around on a leash.

Upon JFK’s premiere, Stone indignantly denied any homophobic intent. JFK was “not about their being gay,” he insisted. “It’s about the connections that being gay makes.” Never mind the absence of any evidence that Ferrie and Shaw ever met, much less plotted to assassinate the president of the United States. The only purpose homosexuality serves in JFK is to signal depravity, sedition, and evil.

The film’s ridiculous thesis is summed up in a line defiantly spoken to Garrison by O’Keefe: “You don’t know shit because you’ve never been fucked in the ass.” Apparently, the terrible truth about the assassination of John F. Kennedy was accessible only to bottoms. That JFK was released just as the number of gay men dying from AIDS was cresting compounds its repugnance.

Even if Shaw was innocent, Stone implied in an interview with Esquire, his prosecution would have been justified. Garrison’s attempt to “force a break in the case” and thereby discredit the Warren Commission was “worth the sacrifice of one man,” he said. It was a chillingly authoritarian sentiment, and in light of how Stone would go on to produce a series of hagiographic films about dictators, including Vladimir Putin, Hugo Chávez, Fidel Castro, and former Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev, a portentous one.

Hounded to the grave by a demagogic district attorney, Clay Shaw can no longer defend himself from Jim Garrison’s calumnies—or Oliver Stone’s. But at a time when prosecutorial abuses and conspiracy theories are undermining faith in our democracy, we would do well to heed the ordeal of a man victimized by both.

James Kirchick is the author of The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues, and the Coming Dark Age. His next book, Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, will be published by Henry Holt in May