The I.R.S. wants to know exactly how much your donation or bequest of art is worth if you claim at least $50,000, and turns to a little-known, secretive body called the Art Advisory Panel of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for help putting an objective monetary value on it.

The panel, which consists of 17 prominent dealers, scholars, and curators from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Toledo Museum of Art, usually meets twice a year to advise the I.R.S.

According to the I.R.S., the panel reviewed 250 items in 2019 (the last year for which figures have been released by the I.R.S.). Taxpayers had valued them at a total of $1.765 billion. The panelists agreed with less than half of the appraisals. The I.R.S. sent the other returns back to the filers and their accountants with new valuations totaling $1.696 billion, an adjustment of about $70 million.

“We are not going to be right 100 percent of the time, but neither do I think we will be far off,” says David Tunick, an art dealer who has been on the panel for 30 years.

As its longest-serving member, Tunick likely remembers the time, in 2012, when the Art Advisory Panel valued one of Robert Rauschenberg’s most well-known works, Canyon, a “combine” that incorporates painting, collage, and a stuffed bald eagle, at $65 million. The heirs of the work, which had belonged to legendary art dealer Ileana Sonnabend, had valued it at $0.

Their reasoning was that the eagle was protected by law and therefore illegal to sell. Three appraisers hired by the estate and Christie’s concluded that Canyon was worth nothing since you could not sell it. The Art Advisory Panel, meanwhile, originally appraised the work at $15 million, then revalued it at $65 million—which meant the heirs owed $29.2 million in taxes.

In 2012, the Art Advisory Panel valued one of Rauschenberg’s most well-known works at $65 million. The heirs of the work had valued it at $0.

The case, which Eric Gibson of The Wall Street Journal said was “tinged more by Kafka than Feydeau,” ended with a deal in which Canyon was donated to the Museum of Modern Art. (No estate taxes were levied, and no deduction was claimed for the gift.) It also put the Art Advisory Panel under scrutiny for the first time. You can understand why they choose to fly under the radar.

“We are not the last word,” says Michael Findlay, a director of Acquavella Galleries, in New York. “The I.R.S. is the last word. They may or may not accept our recommendations. It is entirely up to them. We give them our advice.”

Panel meetings are usually held in Washington, D.C., and are closed to the public. Although there are differences of opinion among panelists, they have not been known to climb on chairs or scream at each other. “It’s collegial, it’s orderly,” Findlay says. “But that doesn’t mean we agree on everything.

“We do not know the identity of the taxpayer or whether a work is being given to a museum, in which case the taxpayer may want a high valuation because it is a tax deduction, or is inheriting it and would want a low value because he or she is going to have to pay tax on it.”

Guessing Games

The Art Advisory Panel was created in 1968 after the I.R.S. began to suspect it was receiving art appraisals that had little resemblance to true market value. There had been what were described as “threatening noises” from Congress, which was looking into eliminating deductibility of the value of artworks in income-tax and estate-tax filings.

The panelists are not paid but are reimbursed for airfare, hotels, and food. They are forbidden from giving details of individual cases. Several weeks before the meetings, they are sent one or two boxes by the I.R.S. containing photographs of artworks, details on the physical condition of the works, provenance, comparable sales figures, and the I.R.S.’s own research. Panel members also go through ethics training prior to meeting.

A leading collector who has donated many works had high praise for the panel. “I always felt that they dealt with considerable integrity,” he says.

Recusals are rare. “It doesn’t happen very often that one of us has a conflict,” said Howard L. Rehs, an art dealer who sits on the panel.

“The only times I’ve actually gone with panel members to look at a work,” says Rehs, “is when there is a big discrepancy—something is valued too high or too low.”

In one instance, members of the panel went to a taxpayer’s apartment to look at a painting that had struck them as “funny” on paper. They found that the painting was actually in two or three pieces—the taxpayer had pushed it together to take the photographs he had sent to the I.R.S.

“We’re in the same room plowing through pages and pages, slide after slide of hundreds of works of art,” said Tunick. “Thank goodness for the occasional comic relief provided by some of my quick-witted fellow panelists.”

During a recent panel meeting, conducted online for the first time due to the coronavirus, ahead of tax day on May 17, the members were shown a photograph of a painting. One member, an art dealer, said, “It’s the kind of picture you would think of for your grandmother.” Another panelist replied, “That’s if you don’t like your grandmother.”

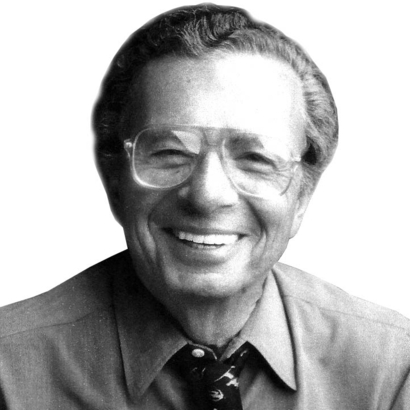

Milton Esterow was the editor and publisher of ARTnews from 1972 to 2014. He currently contributes to The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair