There’s a brilliant scene in This Is Spinal Tap in which Bruno Kirby, as an invasively chatty limo driver, notices in his rearview mirror that David St. Hubbins’s girlfriend is reading Yes I Can, the autobiography of Sammy Davis Jr.

“You know what the title of that book should be?” the driver asks. “‘Yes, I Can—If Frank Sinatra Says It’s O.K.’ ’Cause Frank calls the shots for all of those guys!”

In Unrequited Infatuations, Stevie Van Zandt goes to great lengths to demonstrate that he is no Sammy, no acquiescent lil’ buddy to his friend Bruce Springsteen’s all-powerful Frank.

Dean Martin, now that’s another story. Van Zandt will gladly accept comparison to Francis Albert’s devil-may-care co-conspirator. “In addition to being Italian-American and a fan of Dino,” he writes, “I would use his relationship with Frank Sinatra as my future role model in the E Street Band.”

Like Springsteen, Van Zandt is a New Jersey kid who, despite the Italian blood coursing through his veins, has an unlikely Dutch surname. (His on account of taking his stepfather’s family name; Bruce’s on account of a paternal great-grandfather.)

Unlike Springsteen, Van Zandt leans into his Italian-Americanness. He calls himself Springsteen’s “underboss and consigliere.” He describes the legendary concert promoter Frank Barsalona as “the Godfather.” He punctuates his more forceful declarations with the word “gabeesh.” As is his right—he frickin’ played Silvio Dante in The Sopranos and Jerry Vale in The Irishman, gabeesh?

This florid voice, with which you’re familiar if you’ve ever listened to Van Zandt wax rhapsodic about the Rascals or the Standells on his Little Steven’s Underground Garage program on SiriusXM, translates well to the page. The result is a delightful memoir that, while not as literary and cohesive as Springsteen’s epic autobiography, 2016’s Born to Run, is a whole lotta wild fun, bay-bee.

Like Springsteen, Van Zandt is a New Jersey kid with Italian blood coursing through his veins. Unlike Springsteen, Van Zandt leans into his Italian-Americanness.

A headstrong man, Van Zandt does a lot of flexing, using his book to claw back some claim-to-history credits he believes he has been denied. It was Stevie who had the vision to rescue the Stone Pony, a down-at-the-heels nightclub in Asbury Park, by suggesting to its owners that it re-invent itself as a rock venue. It was also his idea to cut out the second verse of every song in Springsteen’s 2009 Super Bowl halftime show to create room for the band to showcase its latest single, “Working on a Dream.”

And it was our hero who helped Bob Dylan overcome creative stasis in the early 90s by suggesting that Bob record a roots album of folk and blues covers. (Dylan released two such records, Good As I Been to You and World Gone Wrong.)

But Van Zandt is a more complex and multi-dimensional cat than his schmatte-headed, bead-bedecked, braggadocious image would suggest. (In a quick aside, he explains that his “unusual habiliments” are a product of an early-70s car crash that cut up his scalp, wreaking havoc on his hairline and accelerating his dalliance with sartorial flamboyance.)

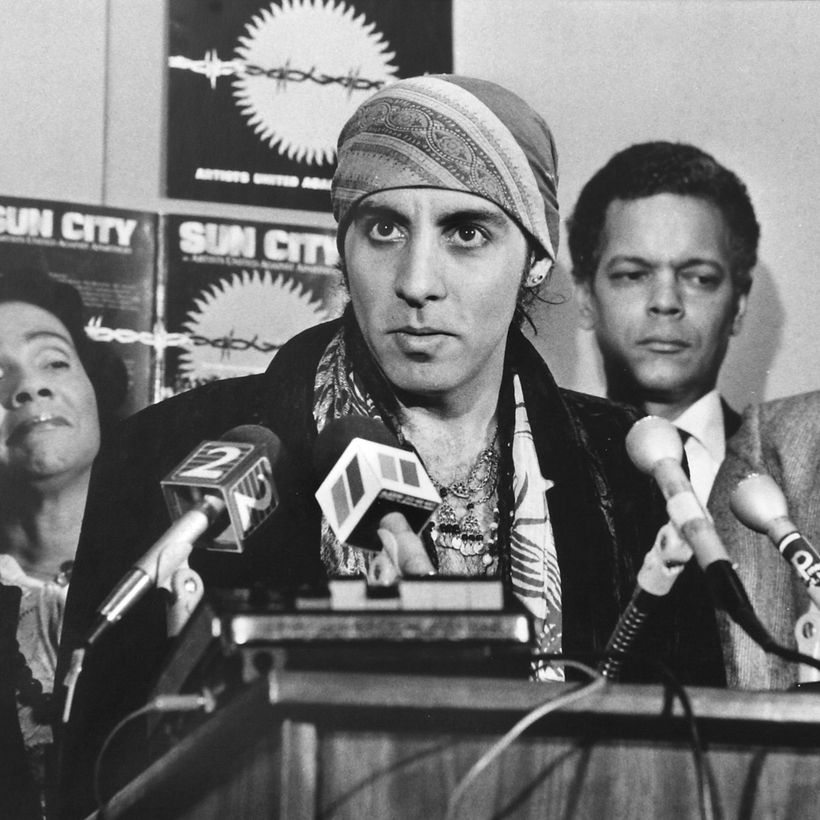

He is an E Streeter but also a fine performer and songwriter in his own right. He is, alongside Lenny Kaye of the Patti Smith Group, one of our foremost curators and caretakers of 1960s rock as an art form. He is, thanks to the persistence of David Chase, a celebrated character actor. And he is a dogged activist, most notably the songwriting and organizational brains behind the funky all-star anti-apartheid anthem “Sun City.”

All of these Van Zandts get a vigorous airing. The “Sun City” stuff is particularly fascinating. Keen not to be merely a dilettante do-gooder, Van Zandt traveled to South Africa, and in one scene we find him meeting in secret with Soweto revolutionaries who are armed with machetes and suspicious of his motives. Van Zandt, at least in his telling, defuses the situation by meeting tough with tough. (“‘Just fucking relax,’ I said.”)

The Sopranos sections are also rich. Van Zandt was, by his own admission, spiraling into cultural irrelevance when Chase came calling, initially wanting him for the Tony role. When James Gandolfini was cast, Van Zandt was given considerable leeway to develop the Silvio character on his own, with a caveat: HBO said it couldn’t afford to build a glitzy nightclub set. That’s why Silvio presided over the considerably more downmarket Bada Bing! strip club instead.

But the crux of any truly worthwhile rock memoir is the struggle—the hard knocks, the overcoming of one-in-a-million odds, the miracle of making something out of nothing. The struggle is the best part of Keith Richards’s Life, which begins with its author scuffing in London fields bombed out by the Blitz, and of Springsteen’s book, in which an introverted working-class kid with a terrifying father wills his way into becoming a Columbia recording artist.

It’s also the best part of Unrequited Infatuations. Van Zandt’s upbringing was much less traumatic than Springsteen’s, but his road to success was just as long and humbling: the bus rides to the city to catch the new acts at Café Wha? in the Village; the penurious days of sharing a hovel of an apartment in Asbury Park with Bruce, the two of them playing Risk while listening to Elmore James records; the sexual education administered by performers from the oldies circuit, who advised the young Stevie to apply cologne to his nether regions. (“It was a different time,” he notes dryly.)

All in all, this book is utterly true to who Van Zandt is. Which is a good thing, like a nice platter of prosciutt’ and gabagool. Gabeesh?

David Kamp is a New York–based writer and the author of Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America