I return to Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina every other year. The novel contains the whole of high society and its passions set against the pull of the pastoral. Movies treat the story as a grand tragic romance, but Tolstoy is more subtle than that. He is revisiting Genesis, transplanting Eve to 19th-century Russia, where (as John Milton puts it) “she plucked, she eat. Earth felt the wound.” Bit by bit Anna loses everything, meanwhile sending dark ripples into the lives of those around her. The Fall of Man—or Woman—never gets old. Recently, however, I wondered why I don’t re-read War and Peace.

To make quick amends, I searched out the famous, and famously long, Soviet film series War and Peace, directed by Sergei Bondarchuk and released in 1966 and 1967. I’d heard about the movie but had never seen it. A trusted friend said that it captured, as no other film has, the long-ago pastimes of the Russian aristocracy—palace balls, sleigh rides, wolf hunts—and this is abundantly true.

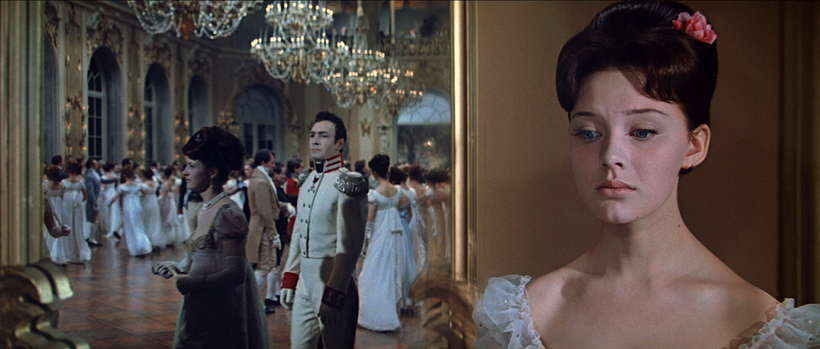

The film’s four sections, made over six years, are Part I: Andrei Bolkonsky, Part II: Natasha Rostova, Part III: The Year 1812, and Part IV: Pierre Bezukhov. During casting, the search for an actress to play Natasha had Soviet starlets aflutter, yet Bondarchuk chose a young ballerina straight from the Vaganova Academy, Ludmila Savelyeva. Audrey Hepburn, also a trained dancer, had played the role in King Vidor’s synthetic War and Peace of 1956, but was too old at 26. Savelyeva, with her big blue eyes and perched emotion, is a fledgling ready to soar.

Being Russian, the role comes naturally to her. In a key scene—Natasha’s dance at Uncle’s cabin in the woods—she performs a folk dance she’s never been taught but is in her blood. Savelyeva is sublime, her classical bearing suddenly sculpted with Slavic inflections. Indeed, the scene is a microcosm for a movie that dances between the philosophical and the instinctual, an opposition that Bondarchuk and his cinematographers often dizzyingly unite.

And never more so than in Part III, a masterpiece of choreographed masses given over to one event—the Battle of Borodino, September 7, 1812. Military buffs will debate this battle in perpetuity; those of us reading about it today may think of the war in Ukraine. Fierce fighting coupled with calculated retreat allowed Russia to defeat Napoleon’s invading forces. Ukraine is doing something similar against Russia. No cinematic battle, even in the movies of Spielberg and Peckinpah, compares with this one for multivalent structure and scale. (The Red Army provided 10,000 soldiers as extras and hundreds of horses.)

From high hilltops we watch myriad divisions advance in endless toy-soldier rows, bullets whining as black smoke blinds. The battle builds to a hellish crescendo of cannon fire, somersaulting horses, galloping chaos. The camera work is omnipotent—aerial, feral, face-to-face, panoramic. “Enough. Enough, mankind,” the narrator pleads, corpses clothing vast fields. As for Napoleon, grabbing at what is not his, Tolstoy sees only ego, arrogance, aggression. “He could not renounce his actions,” the genius writes, “and therefore he had to renounce truth and goodness and everything human.”

The film series War and Peace is available on the Criterion Collection

Laura Jacobs is AIR MAIL’s Arts Intel Report Editor