The naked image of the human body has often caused big trouble. Maybe that’s its point.

The first full-sized image of the female nude in the West was created in marble in the early 4th century BC. It was not universally welcomed. The Greek sculptor Praxiteles produced a naked statue of the goddess Aphrodite (the goddess of “love”, or of “sex”, depending on how coy you want to be). The first client to whom he offered it said a firm “no, thank you”. The next client on the list, the city of Knidos (on the coast of what is now Turkey), said yes. It was a big risk, and the people of Knidos were probably hesitant, but they got a statue that became their big tourist attraction for centuries, the Mona Lisa of the Greco-Roman world. They put it on their coins and it became the staple of their souvenir trade. Yet it always had an edge.

A naked Aphrodite: the Mona Lisa of the Greco-Roman world.

In the ancient world people knew that the female nude could be dangerous, even in cold marble or bronze. One famous story nails that danger. It is said that a young man in Knidos fell in love with this statue of Aphrodite, managed to get locked up with her at night — and made love to her (or, perhaps more accurately, raped her). He got his punishment: according to the stories, he went mad and threw himself off a cliff to his death. Yet he left the proof of what he had done in an indelible stain on the marble goddess’s thigh (which itself became something of an ancient tourist attraction).

When I came across this story as a student, it was a wake-up call. I had always imagined that the idea of the female nude as the object of the “male gaze”, or the sexual possession of its male viewer, was the insight of 1960s and 1970s feminism. That era of feminism got a lot right, but it didn’t invent the sexual politics of the nude. Those politics go back as far as the nude itself, and have always dogged our images of the naked female form.

The Male Gaze, Pre-Feminism

It is these controversies that I have been exploring in The Shock of the Nude, from the world of the ancient Greeks and Romans to the present. Perhaps my favourite painting featured in the programme is Johann Zoffany’s 18th-century view of one of the most exquisite rooms in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, packed full of naked art works. At first sight it looks like a load of art connoisseurs innocently admiring the gallery’s great masterpieces. Yet at a second look you can’t fail to see that there is an awful lot of leering going on. The male visitors (and they are all men, even though we know women came here too) are peering up the bums of the ancient statues, drooling over the naked Titian paintings and happily conflating the love of art with the love of … well, sex. Zoffany, in other words, is reminding us of (and satirising) the “male gaze” long before mid-20th century feminism came along to do the same.

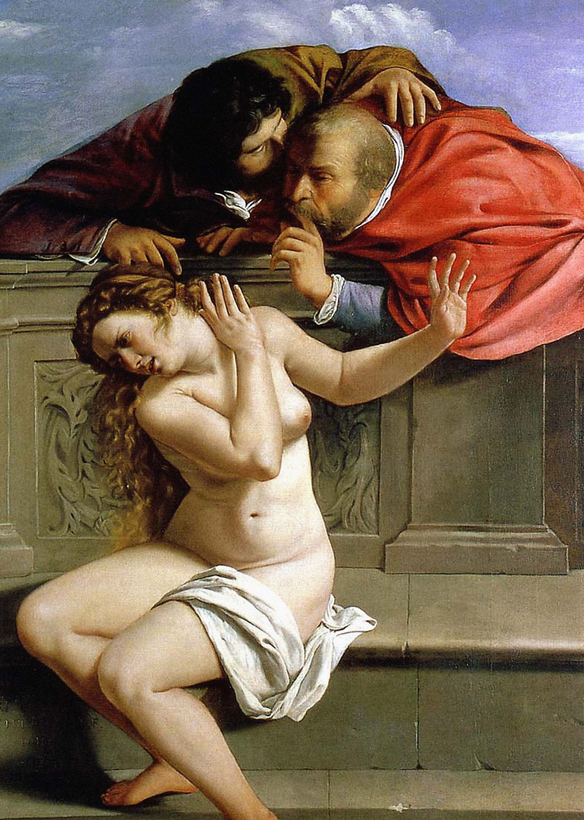

The nude is always about desire and power, from Titian’s Venus of Urbino (the one lying centre stage in Zoffany’s painting) whose fingers come perilously, or titillatingly, close to her genitals, to the terrified female victims of male violence on the canvases of the 17th-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who had herself been raped by her art teacher. Yet there is more to it than that. The nude also raises questions of how we think about ourselves — and of how we see (or refuse to see) the bodies we inhabit, female or male.

Johann Zoffany’s subjects peer up the bums of ancient statues, happily conflating the love of art with the love of … well, sex.

Here those much-ridiculed fig leaves are a big part of the story, decorating the private parts of naked statues. They turn out to be as revealing as they are concealing. It’s easy to imagine that these were a makeshift device driven by Victorian prudishness, a minor cottage industry in the interests of “propriety”. Sometimes they probably were. We were lucky enough to film a memorable moment when, after a couple of centuries of “modesty”, the fig leaves were removed from a set of plaster casts of classical sculpture in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork. The Great Fig Reveal it was called, and it prompted occasional cheers among the people who, like us, had turned up to watch the revelation (in my case even being allowed a go with the chisel). One older lady said to me that she had been waiting for this moment for decades, ever since as a young art student she had been made to draw these plaster casts with their genitals hidden from sight.

I am afraid that she was probably disappointed with what was revealed. To fix the fig leaves on to the sculptures — sometime in the early 19th century, we imagine — most of the penises they were intended to conceal had actually been hacked off. The fig leaves were covering up something that wasn’t there anyway. You might say that their job was not so much to conceal, but quite the reverse: to draw attention to what we should not see, to remind us of what was off-limits.

Who Sees What?

It would be wrong simply to blame the “prudish” Victorians for this. For almost a millennium the question of what bit of whose genitals should be on show, or covered up, has been centre stage and bitterly argued over. The story of the shame of Adam and Eve as they were expelled from the Garden of Eden has certainly played its part in this, but it doesn’t explain everything. Exposure is one thing we have always contested, and still do. In the early 16th century Michelangelo’s David was put on public view in the centre of Florence. It’s now a world famous “classic” plastered over tourist trophies from fridge magnets to tote bags. What is less well known is that, almost as soon as the statue went on display, it was physically attacked. Within a few weeks someone had designed a belt of low-hanging leaves to conceal the penis. The belt was of course an attractive target for Florentine youth (who wouldn’t want to try to take it home?), and an appropriately bulky fig leaf was soon attached, only to be removed in the 20th century.

The fig leaves were covering up something that wasn’t there anyway.

We are still engaged, and enraged, by debates about who sees what. The Renaissance anxieties over David’s willy have their modern descendants. We are just as anxious as any previous generation about the naked body. That came out very clearly in Sonia Boyce’s installation at Manchester Art Gallery in 2018 — which involved taking down a “favourite” Victorian painting, John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (an image of a dreamy young hero being enticed to a watery death by a posse of seductive, bare-breasted pubescent girls). For the most part, this intervention was reported with colossal inaccuracy by the British press. It quickly became a story about censorship, likened to Nazi cultural politics or (of course) to “political correctness gone mad”, and the removal was more or less universally deplored by Middle England and beyond. However, as Boyce explains in The Shock of the Nude, it was never intended that Hylas and the Nymphs should be gone for good. In a sense, by taking it down in a public way Boyce was trying to draw attention to the naked bodies that can seem so at home on gallery walls. What are we looking at when we go gallery-visiting? What is it like for those who work there to be surrounded by naked breast after naked breast, and more?

What did I learn while making the programmes? Three main things. First, I came to see more clearly how fixated western art has been on the nude. Of course, there are wonderful representations of the naked body across the planet (and we focus, in particular, on a glorious example from Nigeria). Yet no other culture has centred its art practice and training on what we call life drawing — in a way that looks just a little weird from the outside. Second, paradoxically perhaps, I began to enjoy the nude more. True, you cannot think about the naked woman in art without thinking about the “male gaze”, but that’s not the be all and end all. I discovered space for a female viewer too, and I scrutinised Titian’s Venus of Urbino with almost as much pleasure as Zoffany’s men. Third, I started to find the relationship between the naked model and the clothed artist and viewer more intriguing and decided that, to understand it better, I would have to do a little modelling myself. Quite how far I went, you will have to wait for the programme to discover.

The Shock of the Nude begins on February 3 on BBC Two.