We forget how young the American musical really is. In his 2013 book Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre, Ethan Mordden organizes that history into four ages. The first finds the musical’s roots in 19-century minstrel shows, burlesque, and the 1866 stage phenomenon The Black Crook. The second age, in the early 20th century, sees forms “consolidating and evolving.” The third, a “Golden Age,” commences in the 1920s, when the musical as we know it took wing. The fourth, which is where we are now, is an age of revivals and “revisals.”

Much of the Golden Age is still within the theater-going experience of many people. For us boomers, the genre-stretching, boundary-breaking musicals of the midcentury were backdrop. My sisters and I may not have been to Broadway, but we had the cast albums. Every night, as we fell asleep, a turntable stacked with LPs would play one side each of Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, and West Side Story. The whir and drop of the needle in the groove, the seconds of static like an existential entr’acte, then songs circling into the subconscious.

We had no idea that Oklahoma! had made a huge leap, that its choreographer Agnes de Mille—learning her psychoanalytical lessons from colleagues Martha Graham and Antony Tudor—had let dance speak for character in a way that deepened and dimensionalized desire onstage. We had no idea that West Side Story—created by Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, and Stephen Sondheim—was a work that defied category, flummoxing critics and launching decades of academic exploration. Was it a musical crossed with classical dance? Operatic tanztheater? Romeo and Juliet by way of Le Sacre du printemps? Bernstein’s own brother, Burton Bernstein, referred to the show as “a monster ballet where no one is actually directed but choreographed instead.” Stephen Sondheim, the show’s lyricist, said to me, “The triumph of West Side Story is that it’s about the theater, not racial prejudice. It’s about how you blend music and dance and dialogue and singing into one seamless whole.”

We had no idea that West Side Story was a work that defied category, flummoxing critics and launching decades of academic exploration.

Oklahoma!, of course, has come in for rethinks that look at the darker facets of Laurey’s longings. Under the direction of Daniel Fish, the 2019 Broadway production that just closed—and begins touring next fall—dispensed with a traditional proscenium stage and opted for a space undone, unstructured (like a barn before its raising, with chili simmering on side tables), an approach that opened up room for millennial textures and fresh questions about democracy, community, and the individual.

Agnes de Mille’s grip on Oklahoma!, however, was nothing like Jerome Robbins’s lock on West Side Story, which he directed and choreographed. One can get into the weeds about the four creators and who thought of what, but the top of the title page reads “Based on a Conception by Jerome Robbins.” And Robbins, nothing if not controlling, guarded his work. That said, he also knew that after he died, the lock would eventually spring and his shows would change.

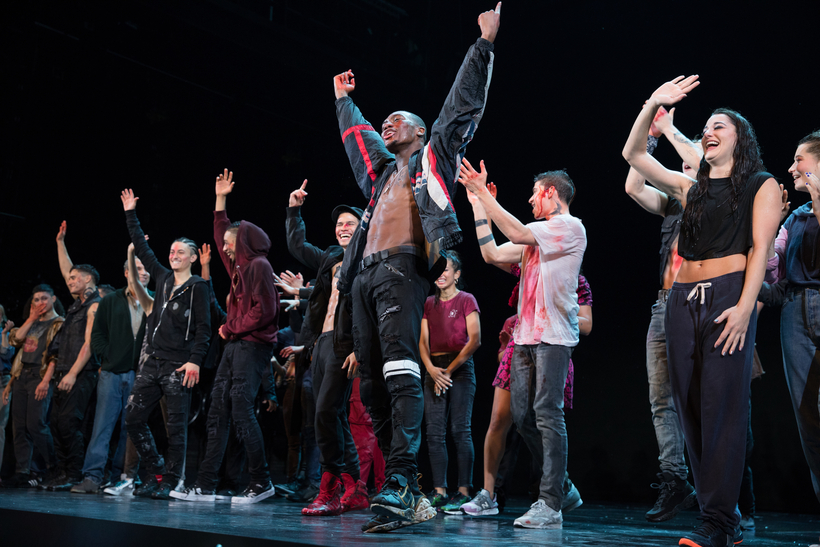

This month, 63 years since the 1957 premiere of West Side Story, a new production directed by Ivo van Hove, with choreography by Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker—both of them Belgian—is set to open on Broadway, on February 20. Van Hove brings his multimedia sensibility to a stripped-down stage. De Keersmaeker, a modern dance minimalist, is known for building expressive power through repeated motifs. It’s a daunting challenge, keeping the whole seamless, especially when two people are stepping into the role of one—a role that requires the creation of a language without words. As the lyricist, director, and producer Martin Charnin, who was a Jet in the 1957 premiere, wrote to me in 2017, “The true libretto of West Side is more in what the dances ‘say,’ than in the book that Arthur wrote, or the music and the lyrics.” Robbins could always do it better in dance.