On April 10, 1970, the music world shifted on its axis with the seismic news that the Beatles had split up. The revelation came after Paul McCartney announced he was officially breaking the bonds of brotherhood with John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr.

Millions of fans instantly went into an emotional tailspin. The band’s Apple offices in London were quickly under siege from thousands of weeping girls (and some boys). And the man from CBS News adopted the kind of somber tone normally reserved for a death in the British royal family, heralding the breakup as “an event so momentous that historians may one day view it as a landmark in the decline of the British Empire.”

Yet, 50 years on from that tremulous day, the Beatles still retain a fascinating foothold in the public psyche. Last year, a rebooted and remastered version of their final album, Abbey Road, was the world’s biggest selling vinyl record. And their download figures underscore their enduring popularity as history’s greatest legacy band for cross-generational appeal.

The overarching question is, Why? The answer is simple. Somehow, the songs they wrote and performed—almost 300 in just seven years—have over the decades been hot-wired into our subconscious to create almost a single brainwave pattern.

End of the Road

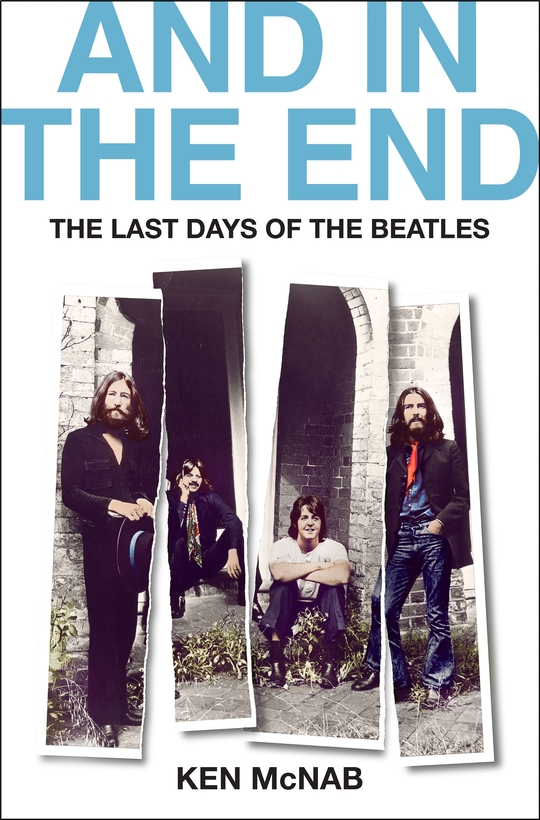

This year I published And In The End: The Last Days of The Beatles, a book that chronicled their final, tumultuous and rancorous months as a functioning band. Even amidst the chaos of their business and personal relationships, creativity still bloomed in the shape of “Let It Be” and Abbey Road, their last love letter to the world.

Nineteen sixty-nine was also the year Lennon emerged as a powerful political activist who aligned himself with those campaigning for the withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam. Lennon’s role as the era’s Pied Piper of Peace is just one of the many threads that were interwoven into the Beatles’ tapestry.

It was the year in which Harrison, the band’s dark horse, snuck up on the inside rail to finally blossom as a singular singer-songwriter with such seminal classics as “Something” and “Here Comes The Sun,” the most popular Beatle song on Spotify.

And it was the year in which McCartney, the band’s cheerleader-in-chief, wrestled with the personal angst of seeing himself slowly being supplanted as Lennon’s closest friend and creative collaborator by Yoko Ono.

CBS News called the Beatles’ break-up “an event so momentous that historians may one day view it as a landmark in the decline of the British Empire.”

The split, when it came, was unavoidable and probably necessary for all their nervous systems. Most fans preferred the notion that the Beatles would end as they started—as four friends who produced some kind of magical reaction, a musical big band. Unfortunately, fate got in the way. Lennon’s tragic murder in New York 40 years ago this December ended all such hopes. But I for one am glad they resisted the multi-million-dollar temptations to reunite.

Perhaps they were indeed a product of the times, avatars of a golden period when it seemed that music really could change the world. When I look at that cover of Abbey Road, I see a band frozen in rock ‘n’ roll amber. And that’s the way history should remember the Beatles—with gratitude for the legacy they left us, a bountiful bequest that continues to thrive in the digital age. Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!

Ken McNab’s And in the End: The Last Days of the Beatles is out now from Thomas Dunne