Out of a cloud of dust and a thundering clop of hooves, Taylor Sheridan has emerged as television’s top auteur-entrepreneur, a singular phenomenon with a surprisingly modest profile. He is a writer (Sicario and the inimitably titled Sicario: Day of the Soldado), but more than a writer; a producer, but more than a producer; a director, but more than a director; he straddles the horizons as a bold concocter and expansionist in an era when nearly everything else in entertainment is being driven by algorithms and clinging to the lifeboats.

With his flagship series Yellowstone, television’s top-rated drama, Sheridan and his team have embarked upon an imaginative re-landscaping and billboarding of the American West that’s closer to the Marvel Cinematic Universe in its scope, detailing, fan recruitment, and muscular flex. The episode titles alone—“Under a Blanket of Red,” “No Kindness for the Coward,” “Meaner than Evil”—tell you we’re not in Julian Fellowes territory, admiring the place settings. The improbable success of Yellowstone has also provided a steady dose of testosterone to the Paramount Network, resolving its long-standing identity crisis.

Yellowstone was a popular hit right out of the gate and has only gotten bigger since. (Its Season Four premiere racked up more than 14 million viewers, an almost unheard-of number in these nichey times. For comparison, Succession’s season finale had 1.4 million viewers.) It was a series audiences didn’t know they craved until it rode into Sunday nights with a full retinue of finely drawn characters, bruising action, high stakes, traditional trappings, scenic wonder, and a modern attitude.

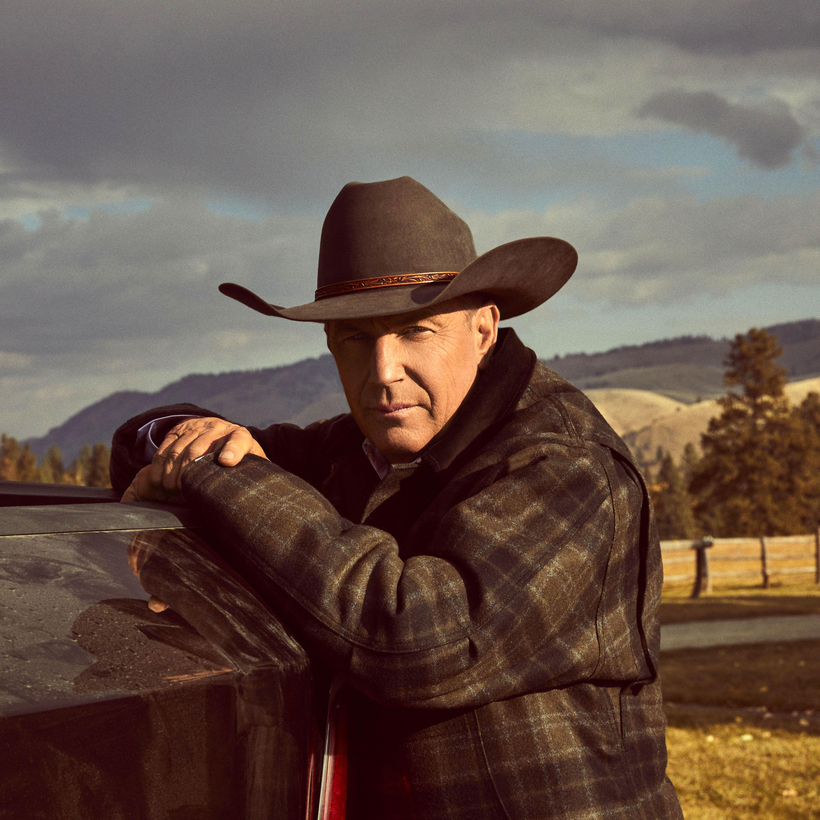

Co-created with John Linson, it is the contemporary saga of a rancher named John Dutton and his troubled brood, whose Montana spread is besieged by greedy, corporate land-grabbers and bedeviled within by sibling rivalry and outbreaks of fisticuffs in the bunkhouse. Put aside your notions of the benign, patriarchal land barons of yore, John Wayne in McLintock! or Lorne Greene’s Ben Cartwright in Bonanza. John Dutton is played by Kevin Costner, who drags the storm clouds with him and the hunched, embattled shoulders of custodial responsibility for the future of his kingdom. “Let a scowl be your umbrella” might be his motto.

A veteran of both contemporary and period Westerns, Costner has the walnut-grained authority and measured containment of a Hollywood star who knows how to apportion his moods and engrave every entrance and exit into a signature moment. He elevates the material by remaining resolutely grounded. His comic timing and phrasing, best displayed in Bull Durham, have not deserted him. The gruff, slow-burn exasperation in his sparring exchanges with his hellcat daughter Beth (Kelly Reilly)—the show’s incendiary device, who drinks, smokes, curses, snarls execrations (“I hope you die of ass cancer”), and wears scary eyeliner—is funny without being played for comic relief. There’s too much scissory tension at the supper table for that.

Sheridan and his team have embarked upon an imaginative re-landscaping and billboarding of the American West that’s closer to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

As in Succession, Yellowstone involves the maneuvering for crown and throne once the old buzzard croaks, but on Succession the bitchy sarcasms are distributed among all the malcontents; here it’s Beth who gets all the good zingers and battle-weary aphorisms, answering her father’s objections to her latest vicious ploy with “Well, that’s life on the Serengeti, Dad.” The menfolk, their cowboy hats worn tight as lids, tend to be on a more dialogue-restricted diet, tending to their psychic wounds and muttering as they head out the door. Like their boss, they adhere to codes of honor all the more powerful for being unspoken. Personal disputes are handled through bare-knuckle brawls because that’s what men do—thrash each other senseless to reach a mutual understanding. Either that, or just shoot the sumbitch.

Yellowstone may have been conceived for television, but visually it conjures cinematic vistas with an old-fashioned sweep of brooding mountains and sunset splendor, its theme music rich with epic swells, as if rising from the earth. It makes the viewer feel part of something bigger, bearing witness to the bitter yet unbowed dénouement of the Great American Procession. Sheridan’s 1883, the prequel billed as the origin story of the Dutton family and starring the real-life country-music royal couple Faith Hill and Tim McGraw, portrays the daunting beginnings of that ragtag procession, the slow trek across the treacherous, unclaimed West for the rocky bosom of Montana. The wagon train is led by that venerable hickory stick with the sheepdog mustache, Sam Elliott. As soon as you hear Elliott’s ornery drawl, you know you’re in for a vintage experience with a heap of gumption.

The premiere episode didn’t stint on incident and teeming bustle, replete with the massacre of a wagon party, a scalping, smallpox, a house aflame, a young lady roughly slapped across the face for being sassy, a street-corner lynching, an attempted rape, the thwarting of said rape with a bullet to the back, and other artifacts of authentic frontier savagery. Lonesome Dove crossed with Deadwood, it was all a bit gaudy for my epicurean tastes, but don’t go by me. Its December 21, 2021, debut earned the highest ratings of any series premiere since 2015, with social engagement also through the roof, further confirmation of the protein appetite Sheridan has tapped.

In Season Four of Yellowstone, the Australian powder keg Jacki Weaver joined the cast as an avaricious baddie with grand designs on the Dutton ranch, at one point laying out her rationale to a sulky, skeptical Beth. “Every resource of Montana can be grown elsewhere,” she explains. “The fantasy of the West is its only resource of any value. Colorado embraced that decades ago. It’s time Montana did the same.” That could be the mission statement of the Yellowstone project: presenting and marketing a real-life fantasy of the West in a horizontally integrated package that includes, so far, Yellowstone, 1883, the reality competition series The Last Cowboy, and, coming later this year, 6666, which is set on the mammoth 266,000-acre ranch that a Sheridan-fronted group of investors purchased in 2020. Episodes of Yellowstone this season featured ancestral flashbacks to 1883 and sidebars set at the “Four Sixes,” featuring a former ranch hand at Yellowstone, Jefferson White’s Jimmy, learning the ropes and being inducted into the ethos and hard-earned fellowship of Texas cowboyin’. The integration goes beyond program content into the merchandising, the ads in Yellowstone and 1883 promoting Ranch Water hard seltzer, Tecovas boots, Ram trucks (John Dutton himself drives a 2013 Heavy Duty Laramie Crew Cab), and, yes, Yellowstone Select bourbon whiskey (which I like to nip after a hard day punching typos), fostering a seamless, ruggedized experience for the viewer—a metaverse that doesn’t require Oculus goggles.

Make no mistake, though, Yellowstone United isn’t an escape portal into a glorified Americana, a theme-park tribute to exceptionalism, a MAGA hoot and holler. A strong undertow of melancholy and resignation suffuses Yellowstone, an elegiac sense that it’s closing time in the canyons of the West, that the good is mostly gone. In one scene we see Beth taking a breather from Lady Macbeth–ing to read The Solace of Open Spaces, by Gretel Ehrlich. A classic, but, oh, the bitter irony. With open spaces shrinking, solace is harder to find, the invasive roar of tractors nearer and nearer, the constant vigilance of defending the Dutton Way of Life exacting an ever higher cost. But a losing battle is better than no battle at all. If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the Serengeti.

Yellowstone is available to watch on Paramount

James Wolcott is a columnist for AIR MAIL