I was sitting outside the Roxy Hotel at midnight one night this past July, after a showing of Ciao! Manhattan next door. Rock ’n’ roll Zelig Danny Fields and artist and actress Bibbe Hansen were there to field questions about Edie Sedgwick, the film’s star, but now everyone was gone. The party was over.

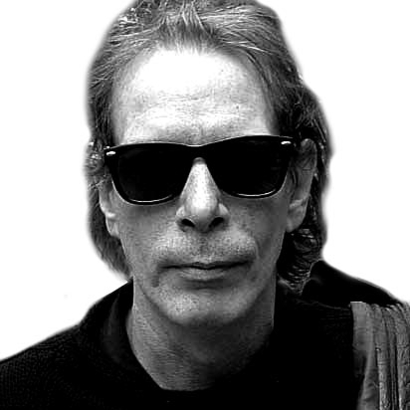

With temperatures over 100 degrees during the day, it was finally cool enough to sit outside and get re-acquainted with the photographer Bob Gruen and his artist wife, Elizabeth Gregory-Gruen, both old friends, when a strange elfin guy with dark, angular eyebrows, curly Charlie Chaplin hair, and a ravaged pair of boots appeared from out of the humid haze and asked if I was Legs.

The guy looked more than out of place. He had a thick Australian accent, but that wasn’t it. There was something unnerving about him, some old-world danger, as he handed me his card and then asked if my wife, Alexis, and I would stand for a portrait in front of the 8-by-10 camera that he kept in the hallway of his room at the Chelsea Hotel. He said his name was Tony.

His request seemed like an invitation from the damned, but who was I to refuse this call to adventure? Except I was so broke. I said, “Yes, but only if you buy us brunch in the morning.” The Count, as I had come to think of him, accepted my offer. We exchanged cell-phone numbers, and he vanished back into the thick, humid night—a phantom who’d gotten what he came for.

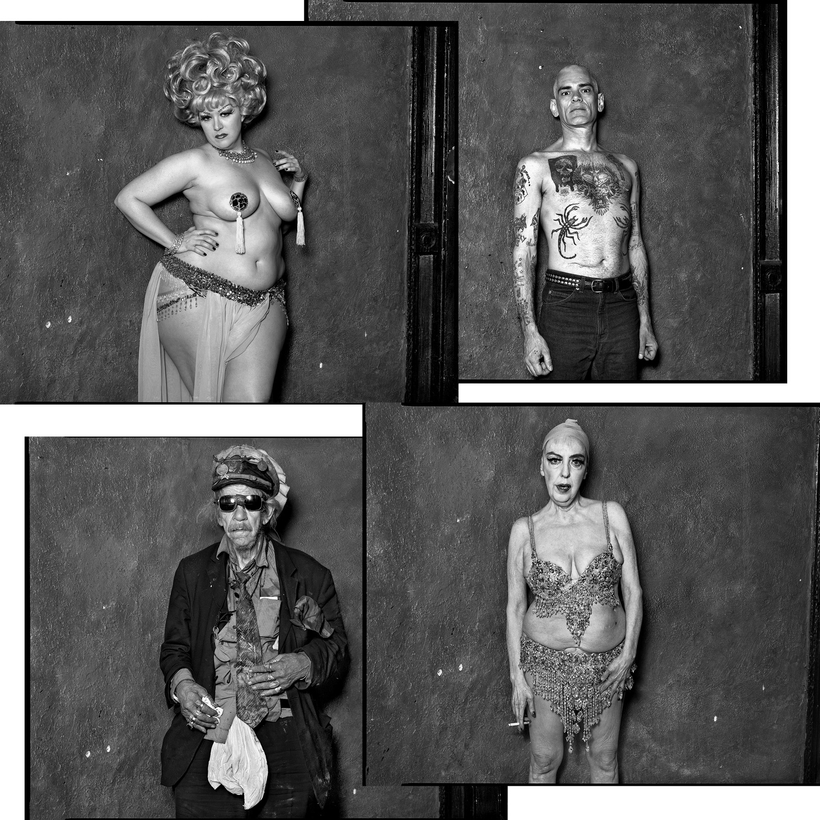

We met the next day at the Malibu Diner around the corner from the hotel for a hearty breakfast. The Count introduced himself as “Tony Chelsea,” explaining his Italian name (Notarberardino) was too long to pronounce. He said that he’d dedicated the last two decades to his book, The Chelsea Hotel Portraits Project, photographing, as he told The Sydney Morning Herald, “the extraordinary cross-section of people who lived at or came to the hotel for one reason or another: tenants, transient hotel guests, staff, actors, writers, circus performers, drug dealers, drifters, porn stars, show girls, musicians and pretty much anyone I found in the lobby or the hallways late at night.”

“Yeah,” I said over breakfast, “but isn’t everyone gone now? Isn’t the Chelsea Hotel now just another renovated soul-less shell of its former self?”

“Why don’t we go see?” Tony grinned mischievously as he paid the check and we walked around the corner to the hotel. There were the dozens of plaques outside the Chelsea’s front door announcing the great works of art created there over the years: one for Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey at the hotel, as well as others paying tribute to Dylan Thomas, Leonard Cohen, Arthur Miller, Brendan Behan, Virgil Thomson, Thomas Wolfe, and James Schuyler, all of whom called the Chelsea Hotel home at one time or another.

He handed me his card and then asked if my wife, Alexis, and I would stand for a portrait in front of the 8-by-10 camera that he kept in the hallway of his room at the Chelsea Hotel.

There was no plaque for Mark Twain, who’d long been forgotten as a resident of the Chelsea Hotel. Neither were there memorials to more recent celebrated residents: Nico, Edie Sedgwick, Janis Joplin, Patti Smith, Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen, or many of the other rock ’n’ roll luminaries who lived there.

We made our way up to the sixth floor and down to the end of the hallway. Tony’s door was painted, with dazzling garish colors, what looked like an acid head’s ridiculous attempt to paint the crazed images inside his mind. When we walked inside, we were immediately transported to another time, another place, another world. Immediately, we knew we’d come to the right place.

Mysticism overflowed from every corner of Tony’s museum-apartment—every shelf, every tabletop, every wall space, and every wonderfully tattered rug. There on the floor of the doorway was a portrait of Padre Pio, the Catholic saint known for his ability to replicate the stigmata. Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, Russian Orthodox, and other religions’ bizarre hybrids were represented elsewhere.

When we came around the corner into the main room, I felt that I’d been lured into the lair of a well-traveled, horny Victorian. There was an inviting velvet couch, Russian oil lamps, lush roses, ornate frames without pictures. And the celestial ceilings! We were mesmerized!

Coco, his white cat, sauntered across the black-and-white checkerboard floor tiles as Count Tony told us of his fascination with freaks, especially circus freaks: sword-swallowers, fire-breathers, strippers, and the like. I said, “Just a hint of Diane Arbus jealousy there?” Tony smiled wide and boomed, “But I love Diane Arbus so much! She’s just the greatest, isn’t she?” I had to agree, adding, “That photo she took of that crazed little boy with the hand grenade has to be the scariest photo I’ve ever seen.” Tony nodded his head and mumbled, “I know, I know … ” And somehow, I knew he did know.

When Tony Met Vali

Tony Notarberardino was born in Melbourne, Australia. The Italian section of Melbourne was a close-knit community with its own movie theater that Tony inhabited every Saturday night to marvel over the neo-realist films of Rossellini, De Sica, Pasolini, Fellini, and Antonioni and dream himself into that life. When I gushed over Charlotte Rampling in The Night Porter, Tony quickly scurried to a hidden closet where all his valuable artwork is locked away in large unmarked manilla envelopes, but he couldn’t find his original film poster, so we skipped to the next fascinating subject.

In 1993, Notarberardino’s cinematic photography caught the attention of Vogue editors, which resulted in his first editorial commission, which soon led to others in Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, Marie Claire, Elle, and GQ. Tony says his commercial work was just a way to pay his bills, but it did allow him to live in Paris, London, and Milan. Still, there was something missing from his life, which is why he saved moving to New York for his last great adventure. Tony arrived in 1994 and checked into the Chelsea. His neighbor was a woman named Vali Myers. “Vali was this incredible dancer, tattooist, and fantasy artist that was born in 1930,” Tony said.

At 19, Vali had traveled to Paris looking for work as a dancer, but wasn’t prepared for what the ravages of war can do to a city, and was left homeless on the Left Bank, where, according to An Cathach magazine, Ed van der Elsken made Vali the main subject of the 1958 photobook Love on the Left Bank, which also featured some of her art. With her Snidely Whiplash–mustache tattoo and her flaming red hair, Vali became infamous and found herself hanging out with Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Cocteau, Tennessee Williams, and Jean Genet. She also developed a wicked opium habit.

In 1970, Vali moved to New York, where she was introduced to the Chelsea Hotel by Abbie Hoffman. Once she moved in, Andy Warhol encouraged her to start exhibiting her fantasy artwork, which mixed pointillism with watercolors for a dazzling effect. Salvador Dalí convinced her to do a show in Amsterdam, where she wowed the art world. Even Mick Jagger collected her work.

“In 1993,” Tony continues, “at age 73, Vali moved back to our hometown of Melbourne, Australia, and I somehow inherited her apartment [in the Chelsea], though we remained friends and I always saw her on my returns to Melbourne to visit my parents.”

“My next-door neighbor, Dee Dee Ramone, was the only problem,” Tony says. “I’d be walking down the hallway with my friends and they would say, ‘There’s a homeless guy sleeping in your doorway!’ ‘No,’ I’d say, ‘that’s just Dee Dee Ramone.’ I’d always ask him as he was snoozing on my doorstep if he wanted to sleep on my couch and he’d tell me to fuck off. Two minutes later there would be a knock on my door, and I’d let him in and put him to sleep on my couch. The real problem were the arguments between Dee Dee and his young wife, Barbara. They were always yelling at each other. But eventually Dee Dee and Barbara moved out, and I acquired Dee Dee’s apartment. So, with Vali Myers’s apartment, now I have two wonderful apartments inside the Chelsea Hotel, preserved to their former grandeur.”

It was inconceivable to me that Count Tony could maintain this bohemian paradise in the midst of New York’s cutthroat real-estate jungle. So I asked him how he managed to prevail.

“Since the Stanley Bard family sold the hotel, in 2010,” Tony explained, “there have been three other owners. The latest owner, Sean MacPherson, seems to be much more amicable and more inclined to preserve what is left of the real Chelsea Hotel!”

Tony also remembers Stanley Bard fondly. Stanley was the Chelsea Hotel innkeeper who would accept artwork, like Vali Myers’s paintings or Warhol’s silkscreens, in lieu of rent, and was a guy you could reason with if you were a little short that month. One day, Stanley called and told Tony that his old friend Arthur C. Clarke was in town for a conference and asked if he could drop by. “If you take a photo of me and Arthur in the Chelsea Hotel doorway,” Tony remembers Stanley telling him, “I will make the introduction and you can take it from there.”

Vali became infamous and found herself hanging out with Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Cocteau, Tennessee Williams, and Jean Genet.

“Arthur C. Clarke was writing all these great science-fiction books in the 1940s and 1950s that predicted what is now satellite technology,” Tony says. “Well, all these young kids read his books and became NASA physicists and engineers who invented satellites, and they invited him to some science conference in the 1990s, because they wanted to hang out with him.

“By this time, he was in a wheelchair,” he continues. “I wheeled him up to my room, where he stood up and let me take his portrait. I believe that was the only time he stood up. He talked about how much fun it was writing the script with Stanley Kubrick at the Chelsea. After we finished the portrait, Arthur asked me to wheel him down Eighth Avenue to some bookstore that featured a lot of sci-fi books, and I did. He was really enjoying himself browsing the collections when someone recognized him, and all hell broke loose! Arthur was quickly engulfed by fans wanting his autograph and to talk to him. But luckily, we escaped with our lives.”

For the past two decades, Tony has been scouring the Chelsea for interesting people to photograph for his book, The Chelsea Hotel Portraits Project, all shot on his huge 8-by-10 camera, which is mounted permanently in his hallway. While his apartments are alive with color, Tony’s photos are stark black and white—portraits of the damned.

My favorite is his portrait of Dee Dee Ramone, a friend of mine since 1975 and one of the oddest people I’ve ever met. He was once one of the cutest boys on the punk scene, but in Tony’s rendition, Dee Dee is represented as a ravaged monster, bare from the chest up, revealing dozens of ugly tattoos as he scowls at the camera, waiting for the remark that will trigger his next tantrum.

Tony captured Dee Dee in all his psychotic splendor in a menacing but chillingly honest picture of a man destroyed by fame, drugs, mental illness, and the inability to find a place where he belonged. That’s Tony Notarberardino’s specialty: people who don’t belong. Which is why the Chelsea Hotel, even in 2022, is the perfect place to set up shop and catalogue the dispossessed. Luckily, they will find a friend in Count Tony, lurking in the lobby, waiting to greet them after midnight and escort them to his lair, where he will capture their soul for all the world to see.

Legs McNeil is the co-author of Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk and The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry