You might say my idea of a hero has been on a downwardly mobile spiral over the course of my life. My first heroes were famous baseball players, and when I was nine years old I could tell you why—like Mickey Mantle, because he could bat both righty and lefty, hit for both power and average, and run and field, too. Most guys could only do one or two of those things at the highest level, but he could do them all. That was enough to make him a hero for me.

In college, my heroes were famous jazz musicians, and I could tell you why—like John Coltrane for creating “sheets of sound” that aimed for spiritual transcendence. I wished he was still alive so I could see him perform. And Miles Davis for fusing jazz and rock—with virtuoso instrument playing by people like Chick Corea and John McLaughlin, who married the older genre of jazz improv to the electric sounds that expressed more of what I felt. And Joni Mitchell, for fusing that electric jazz with folk music and poetry. They weren’t as famous in America as Mickey Mantle, but they were, of course, giants, and deeper inspirations to the people who knew their work.

As a young journalist in my 20s, my heroes became history-changing human-rights activists from before my time, like Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Martin Luther King Jr. That’s as obvious, and obviously worthy, as it gets, and they were, of course, world-renowned, not for their personal athletic or artistic accomplishments, but on behalf of the poor and marginalized. And in King’s and Gandhi’s cases, at constant risk to their personal health and safety. One of the great privileges of my life has been to co-host public Martin Luther King’s–birthday events the last 15 years. Come join us next January at the Apollo Theater if we’re doing events in person again by then.

But even the greatest of public figures or the bravest of risk-takers are not where a discussion of heroism should end, and not where my idea of it stopped changing. In my 30s, I married a social worker and came to realize that while she was in the trenches every day, helping people with AIDS or addictions or not enough to eat, I was the one who strangers thanked for my work when we walked down the street, because they hear me talk on the radio. When I later hosted some events for social workers—also for librarians—I included an invitation to give themselves a round of applause because musicians and ballplayers and radio hosts get that from audiences, but they never do. That these are historically female professions also suppressed how much glory they were seen to confer. At least they could give a standing ovation to each other.

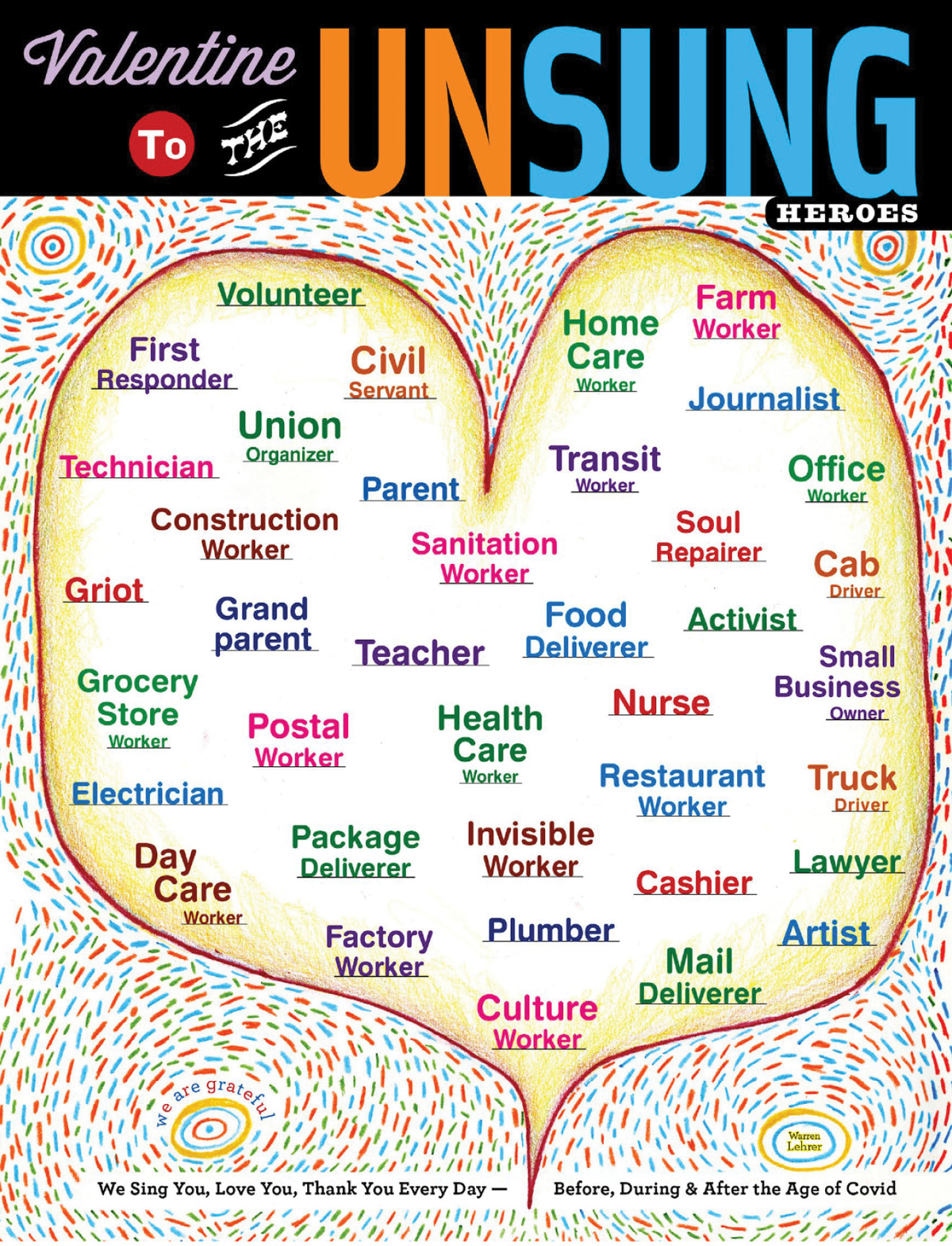

In this volume, one of the contributing artists is my amazing brother, Warren Lehrer, who composed his page around “essential workers”—from first responders to package deliverers—as the heroes of our time. I’m with him, and, for my part, I can tell you why—not just for things like delivering my packages in a virus-soaked world, but for taking this risk in so many cases to support their families. In the old days, it never occurred to me to consider things like someone’s family life (hello, Miles) or how they treated their employees before I gave them hero status. Now that status has devolved for me from the public realm to the private, from the singular to the group.

Lately I’ve been grief-bingeing on videos of Chick Corea, who died this year, who I’d say I once idolized, and who may have brought me more joy over his career than any other musician. But it wasn’t hero worship I was feeling anymore. It was just love. And yet, when listeners ask me what it’s like to interview people’s “heroes” on my show, I have to be honest. I’ve had heads of state, some of the world’s greatest scientists and philosophers, Nobel Peace Prize winners, you name it. Generally, I tend to be more curious than star-struck. But when Yogi Berra was in my studio (to promote the Montclair, New Jersey, public library!) that was who I asked for an autograph. And when Wynton Marsalis was there, I was all jelly-legged and saying to myself, “Please don’t sound like an idiot in front of Wynton.” So some impulses die hard.

While doing some homework for this piece, I did the obligatory dictionary search, and was surprised to see that Merriam-Webster’s first entry for “hero” is not of someone real but someone imagined: “a mythological or legendary figure often of divine descent endowed with great strength or ability.” It wasn’t until the third entry that I saw something like what I had expected, “a person admired for achievements or noble qualities.” Courage was only mentioned in entry No. 4. Here I was, writing about earthy grinders like Gandhi and social workers, and the first dictionary definition of hero was of someone completely made up.

But I think I get it. Anointing someone a hero can require some imagination. A person may do something high-achieving or noble for its own sake, very concrete, maybe very dangerous, then other people put them on a pedestal and call them the h-word. That doesn’t diminish what the hero accomplished, but it also satisfies a need of the person pinning the label on them—an understandable human desire to have people to look up to as pinnacles, and maybe to see as a little bit larger-than-life, a little bit legendary, a little bit mythological, in ways that make us aspire to be our best selves. So O.K., yes, I shouldn’t get too contrarian. Heroes can be public figures, and they don’t even have to be real to do some good.

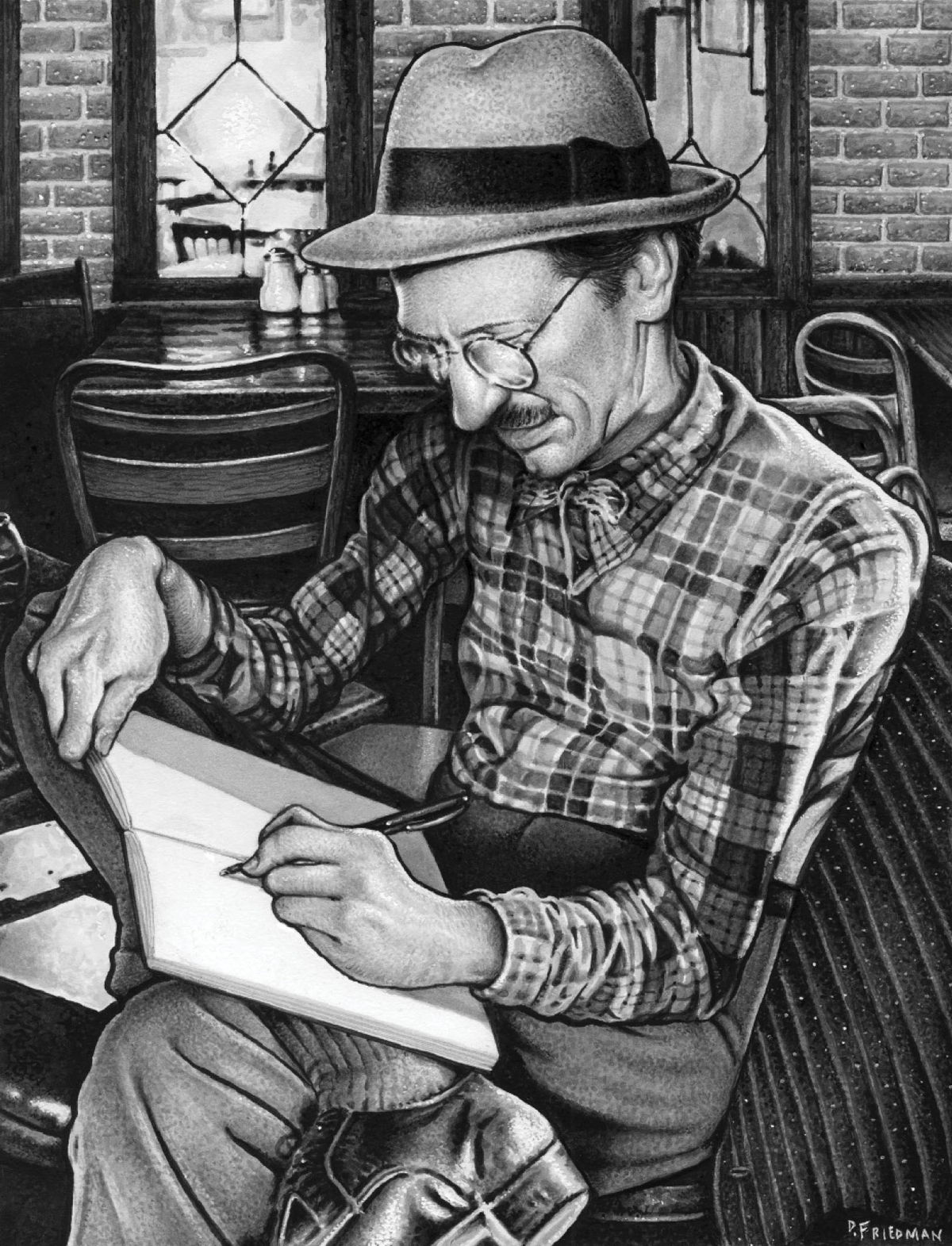

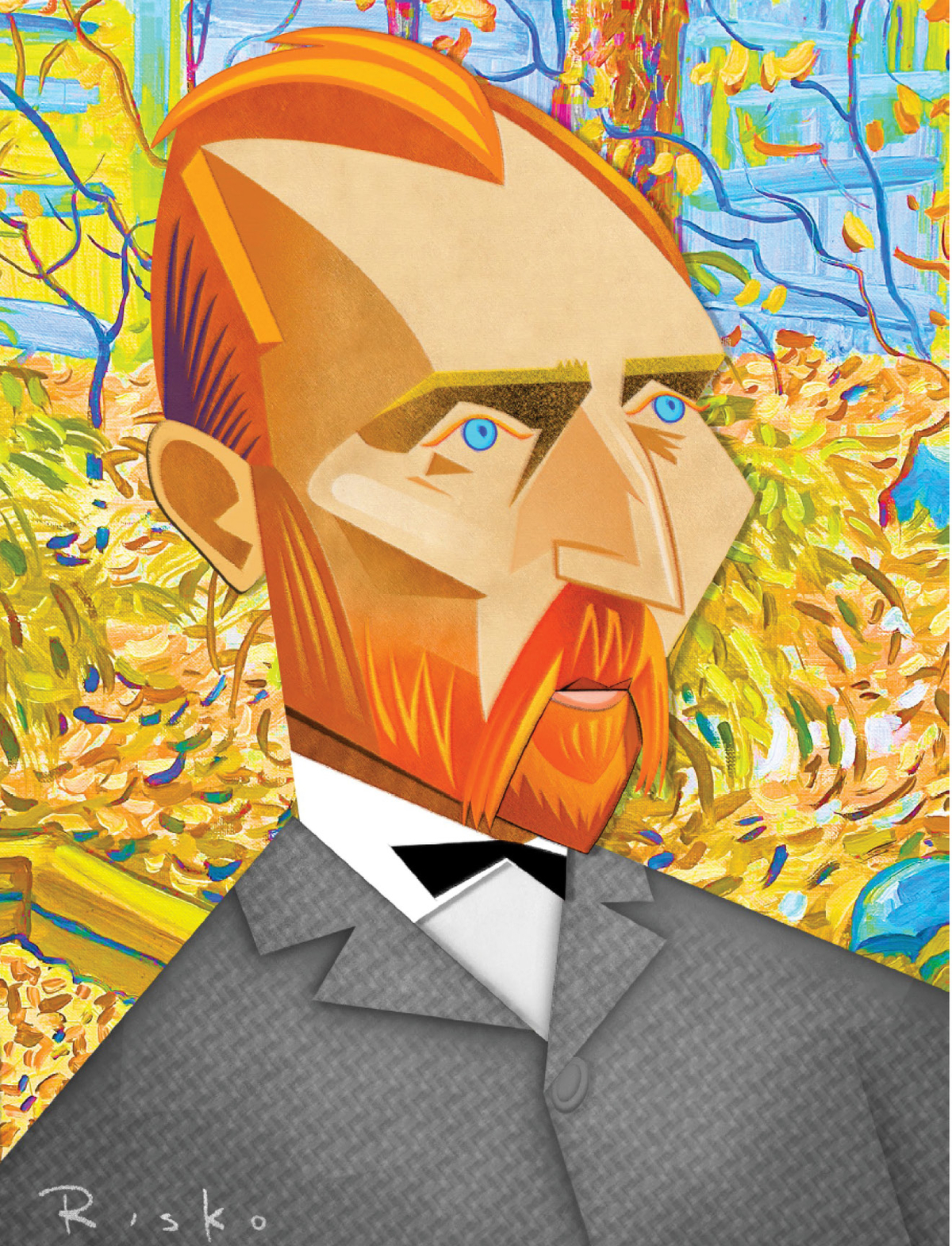

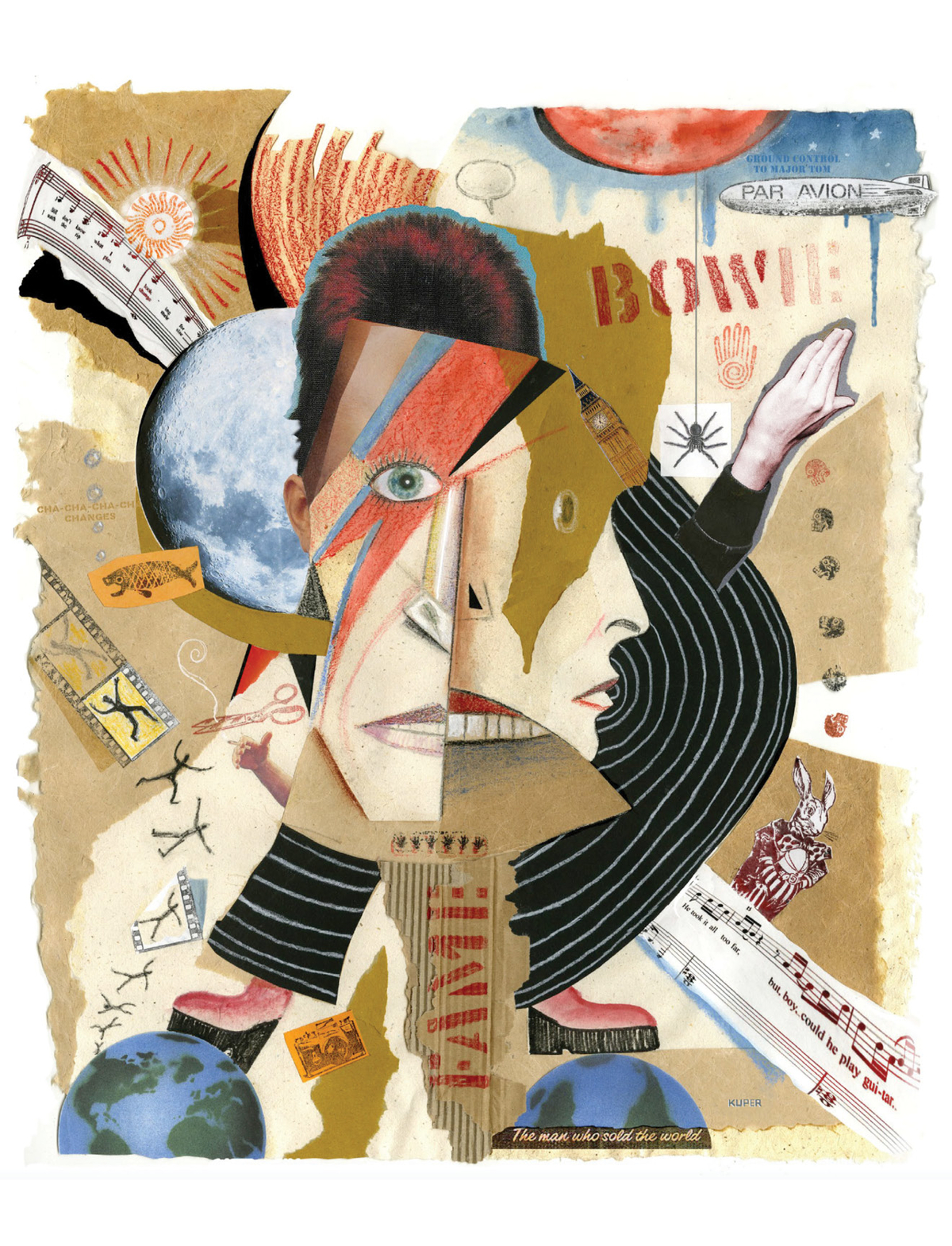

This magazine of language and art creates an ecstatic street festival at the intersection of those dictionary definitions. For the most part, the heroes are real and famous people. But the imagination of the artists takes us to that visual, visceral, next-level place, that’s as much about how the hero makes them feel as about what the hero did. Enjoy Kate Sullivan’s take (with a cake!) on Stacey Abrams, Karen Barbour on her sister, or Mitch O’Connell on Jesus. But also check out Meg Hitchcock, whose selected hero is “Tibetan Buddhism,” Daniele Melani, who picked “Wildflowers,” and Elizabeth Haidle, who makes a hero of “slow things.” Legendary and mythological indeed!

So revel in this collection. You won’t be able to help but think and feel, laugh and cry, and maybe get inspired to up your game—on the ball field, on the political battlefield, or on your kid’s remote-learning app. And maybe afterward we’ll all get on Zoom together and agree that our hero is art itself.

An animated version of Public Eye, Volume I: Heroes is available on Instagram (@publiceyeart)

Brian Lehrer is the host of the Peabody Award–winning The Brian Lehrer Show, which airs on WNYC Radio Mondays through Fridays 10 A.M. to 12 P.M. E.T. The show is also available anytime at wnyc.org