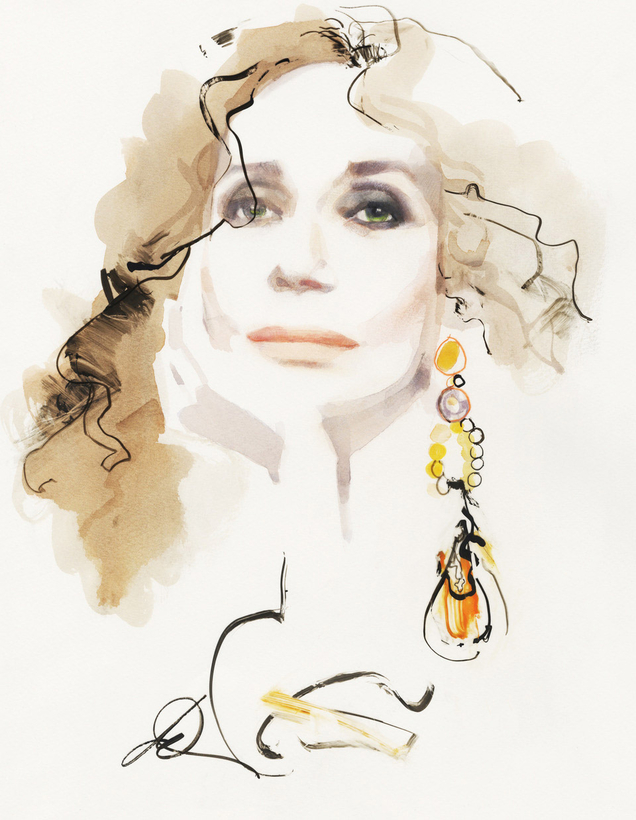

As the youthquake reached a crescendo in the mid-1960s, a trio of aristocratic young women were dominating the pages of Vogue, championed by its editor, Diana Vreeland. They were Penelope Tree, the offbeat “anti-beauty” beauty; Veruschka, epic, exotic, and as imposing as a Vesuvian guard; and Marisa Berenson, the chameleon of the group. Green-eyed and spider-lashed, she gazed from countless covers of the magazine, swinging through layouts in Paco Rabanne and Courrèges, or reclining naked on a beach at sunset, or posing on the roof of the Blue Mosque in Turkey.

Marisa was everywhere. But who was Marisa?

Marisa was born in New York in 1947 and educated in Europe, and her father was a director of Aristotle Onassis’s shipping company and later a foreign-service envoy. Her maternal grandmother, the iconoclastic couturier Elsa Schiaparelli, was descended from the Medici. “She was the backbone of the family, discreet, very strict, very severe,” says Marisa. “She had closed her business by then and never discussed it. It was only later through Yves [Saint Laurent] and Hubert [de Givenchy] that I really understood her influence, her legacy.”

“We must photograph Marisa!” declared Vreeland, a family friend, when Marisa moved to New York in 1965, following the death of her father. Shy and painfully insecure, Marisa wasn’t convinced. But Vreeland marshaled her forces, and within weeks the teenager was working with the defining photographers of the era: Bert Stern and David Bailey, Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, Cecil Beaton and Guy Bourdin.

On a photo shoot in India, she found herself on the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. George Harrison and Ringo Starr were there. And Mia Farrow. (It was the late 60s, after all.) Marisa stayed on and began practicing Transcendental Meditation. “It changed my life. I was searching, meditating. Looking for the light. I found my spiritual path and I have never deviated from it. Given everything that happened later, I must say it saved me.” Her timing was perfect. The 1970s were right around the corner.

Keen to try acting, she began taking lessons and quietly testing herself Off Off Broadway. Looks and pedigree and connections will out. She met Italian director Luchino Visconti through her boyfriend, the late Austrian actor Helmut Berger. “We loved each other,” she says of Berger today. “He was the most beautiful, fascinating man. He had everything. But he had a basic malaise. He didn’t know how to be happy.”

“We must photograph Marisa!”

Visconti (who had been Berger’s mentor and former paramour) offered her the role of Dirk Bogarde’s histrionic young wife in Death in Venice (1971). On her first day of shooting, on a set crowded with extras, she was required to weep and faint. Visconti likened her to Sarah Bernhardt. It was the affirmation she needed.

She was the patrician Fraulein Landauer in Bob Fosse’s Cabaret (1972). “What is screwing?” she inquires primly under the sweeping brim of a hat during an English lesson. Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli) has the answer. The role won her two Golden Globe nominations and brought her to the attention of Stanley Kubrick, who cast her in Barry Lyndon, based on the book by William Makepeace Thackeray.

The shoot took more than a year, relocating from Ireland to London after three months and exhausting everyone involved. Ravishing and mainly silent, she moves through the movie like a wraith, as pale as pewter, a Gainsborough come to life. A disappointment (though not a financial failure) on release, the film is now acknowledged as one of Kubrick’s masterpieces. “You will never be more beautiful on film,” the director told her, a truth she acknowledges today.

It was Marisa’s moment. Yves Saint Laurent declared her “the girl of the 70s.” The covers of Time, Newsweek, and Interview bore him out. Dazzling in Halston (her “big brother”) at Studio 54 with Truman and Andy; fur-clad in Klosters with Helmut Berger, she was the jet set’s new darling, the Queen of the Scene. “It was an amazing time. An era of creativity and freedom and joie de vivre. I floated through it all. Everyone laughed at me: ‘Oh, there’s Marisa, eating lotus leaves and meditating.’ I never did drugs. I was never attracted to the dark side. I was in that world but not of it.”

In 1976, she married business tycoon James Randall in a Hollywood ceremony attended by 800 people. (Berger was so disruptive he had to be escorted from the room.) The marriage didn’t last, but it did produce a beloved daughter, Starlite. A second marriage, to lawyer Aaron Golub, ended in divorce in 1987.

Paradoxically, cinema was entering an anti-glamour era, and initially Marisa struggled to find her place. Casanova & Co. (1977), with Tony Curtis, and Killer Fish (1979), produced by Carlo Ponti, were not high points. “I made the best films, and the worst!” she laughs. Among the best were Clint Eastwood’s White Hunter Black Heart (1990) and Luca Guadagnino’s I Am Love (2009).

On September 11, 2001, her younger sister, Berry, was killed in the first plane to hit the Twin Towers. A private tragedy played out in public. It was her darkest hour, made bearable only by the faith she had nurtured since the 1960s.

Since then, determined to challenge herself (“You have to have courage”), she has taken on Shakespeare for Kenneth Branagh and co-director Rob Ashford in the West End, and played a Weimar chanteuse in Berlin Kabarett, onstage in Paris in 2018, fulfilling a lifelong ambition to sing and dance.

Now based in a villa outside Marrakech (“my paradise”), surrounded by nature, she can look back with equanimity. “I am grateful for the people I met who changed me and contributed to my life. I was so lucky. I had the best mentors. But other people live in my past more than I do.”

Too busy for nostalgia, she has set up her own production company, is in three soon-to-be-released films, and launched her first jewelry collection in April. In early July, she was back in Paris for the haute couture shows, rallying to the flag of the designers she favors, among them Daniel Roseberry, creative director of Schiaparelli. “My grandmother would be smiling. He’s put Schiaparelli back in the light. Grandeur, elegance, originality.” Marisa should know.

David Downton is an Editor at Large for AIR MAIL