Artists tend to present themselves as they wish to be seen in their paintings. Through their letters, if we are lucky and any remain, we sometimes glimpse the less contrived reality.

In 1784, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founding president of the Royal Academy of Arts, wrote Charles, the fourth Duke of Rutland, about the “honour” of being sworn in as “principal painter”: “The Place which I have the honour of holding of the Kings principal painter is a place of not so much profit and of near equal dignity with his Majestys Rat-catcher. The salary is £38 per annum and for every whole-length I am to [be] paid £50 insteed of £200 which I have from every body else. Your Grace sees that this new honour is not likely to elate me very much.”

To another, Reynolds recognized that “a painter who has no rivals, and who never sees better works than his own, is but too apt to rest satisfied, and not take what appears to be a needless trouble, of exerting himself to the utmost, pressing his Genius as far as it will go.” It is this Reynolds, the amusing, self-aware striver, not the noble portraitist or prescriptive R.A. lecturer, that Dr. Johnson, James Boswell, and Oliver Goldsmith were fond of.

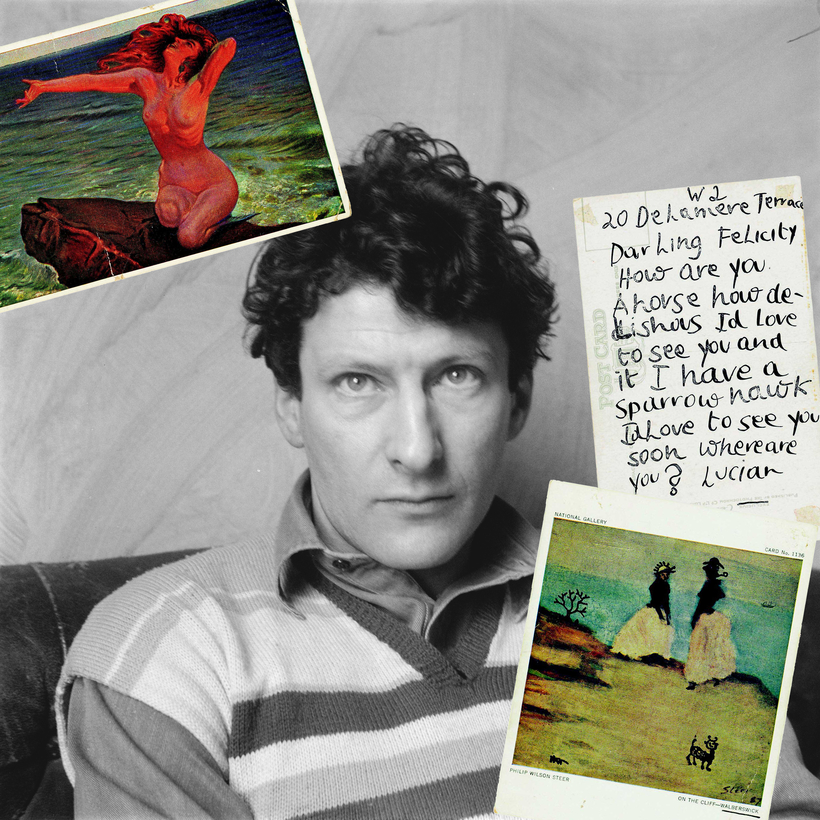

Technology has no doubt closed off many such views. Fortunately, practicality was no match for the young Lucian Freud’s affectations. “Even in the 1940s and 1950s,” David Dawson and Martin Gayford relate in the introduction to Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud, 1939–1954, “he was eccentric in generally not having a telephone.” I am inclined to agree that their volume is “among the most revealing, illuminating, and entertaining collections of artist’s letters in existence.” Love Lucian is beautifully presented, and contextualized with wit and an expert’s discernment. It doesn’t hurt that Freud was one of the century’s great talkers, rogues, and talents.

He was born in 1922 in Berlin. His father, Ernst, was an architect and the youngest son of Sigmund. According to Freud, his mother, Lucie, “was intuitive” about his contrariness: “I wouldn’t say that she knew exactly what was going on in my mind, but she could get quite close. She used to say, ‘I know it’s quite certain that you are going to go to jail, and it will be better after that has happened, when you come out.’” Of his decision to paint full-time, he would say, “Since my mother was so keen on my becoming an artist that it made me feel sick, it was a good thing in a way that my father was against it. If they’d both been in favour, I’d have had to become a jockey.”

The earliest letters featured, written around age nine, are notable for their carefully colored text, the frequent, stylized appearance of “LUX,” his childhood nickname, and inscriptions in an alphabet he had apparently invented. In an undated but likely contemporary letter, Freud depicts an upended, bedridden fish with the plaintive triple notation “KASPER iST KRANK” (“Kasper is ill”).

Ernst moved the family to London in 1933. Lucian was sent to board at Dartington Hall, in Devon, on the basis, it seems, that they accepted pupils who couldn’t speak English. His life there centered on animals rather than books. In one of the editors’ typically hilarious asides, an elderly Freud schools an 11-year-old on goats: “He explained how he knew a bit about goats, having looked after them at Dartington, and felt that what was described in a play that he had seen, The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?, by Edward Albee, showed a complete lack of understanding of goatlike behaviour.”

Serial expulsion brought him, in 1939, to the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, in Dedham, run by Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines. That year, Freud began capitalizing or underlining ingenuous requests for cash (“PLEASE SEND ME MONEY”) and regularly punctuating his letters with drawings. A man kicking himself (with accompanying speech bubble: “whos kicking me?”) ends one letter; the heraldic design for his pretend business with the poet Stephen Spender, “Freud and Schuster,” sits atop another.

Freud’s stint as an ordinary seaman during the war produced hurried correspondence, fine studies, and unconventional experience. “One of the other sailors once asked a question,” he recalled. “‘When you meet someone, what’s the first thing about them you notice?’ I couldn’t think of the answer, so eventually I asked him, ‘Well, when you meet someone, what do you notice first?’ ‘Whether I could beat them in a fight, of course!’”

Freud evaded military service by laying “great stress” in his medical examination “on his love of fires and request[ing] a private room in barracks to prevent his being molested at night by other soldiers.” Remember “love of fires” whenever you are next summoned to jury duty or an unwelcome date.

A 1942 letter to his girlfriend, Felicity Hellaby, reveals an unexpected sideline in films. In one, Much Too Shy (1942), Freud played an art-student extra: “I was supposed to be painting at an easel. The director [a French-born veteran of British comedy named Marcel Varnel] came up to me and said, ‘You don’t know anything about how to paint, do you? Look, I’ll show you.’” Varnel proceeded to throw back his head, survey “dramatically,” and paint “with a flourish.”

Unsurprisingly, Freud shifted his tone, style, and penmanship depending on his correspondent. As Dawson and Gayford note, there is “an enormous difference between the careful calligraphy of his surviving letter to Kenneth Clark” and whisky-soaked scrawls to his friend and fellow painter John Craxton. To special recipients Freud deployed outré postcards “where you pull levers and people start doing acrobatics or change their clothes, disrobe and change into witches.” On the versos were everyday trivia: “I find Ive grown a beard by mistake so I think I will shave it off now.”

Through the mid-1950s, we observe Freud growing artistically, if not personally. (Lincoln Kirstein was not alone in admiring “Lucian’s work but not … his behavior.”) A “destructive and unscrupulous” presence, he was the sort of guest who might—and did—spill ink on his sheets and set fire to his bed. (These were separate incidents.)

Ernst continued to misjudge Lucian’s work, offering well-meaning advice: “A well-composed picture can not be a hit or miss—altho’ you may make a hit one, there will be many misses which give a curious unbalanced sensation when looked at. The various parts of the composition can only be related to the whole if thought out in relation to the whole.… I do think that you genuinely have difficulty in seeing things all in one piece or perspective.”

Freud appears not to have heeded his father. Yet Love Lucian keeps the whole always in view.

Max Carter is vice-chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art at Christie’s in New York