Faced with the test of threading a sewing machine, in ninth-grade Home Ec, I still remember my fear. I knew the thread’s path through the various guides and levers but dreaded the last passage—poking it through the slit eye of that vertical exclamation point, the needle. So much emotion focused on such a small act. But was it small? Threading a needle, darning a sock, finessing a French braid or playing cat’s cradle, mastering scout’s and sailor’s knots, learning to knit, sew, and smock … All these little tests and games, these early encounters with hair, string, and skein, are early exercises of the hand-eye coordination that makes us human. For some, the thread unspools into the labyrinth of art.

Loomed, woven, and knotted, yarns of wool, silk, camelhair, and cotton make up some of the most spectacular works of art in Western and Eastern history. Look back 500 years and the tapestry masterpieces of Gobelins, in France, have their match in the magisterial rugs of Safavid Persia and Mughal India. That such works have traditionally been the product of female fingers, a motor refinement quick and quiet, just adds to their grandeur. They are largely, phenomenally, anonymous, and transcend signature.

While the tapestries, which hang, tell stories with a cinematic sense of time, the rugs, intended to lie flat, are wish fulfillments of self-contained, ever-regenerating energy and plenty. “They suggest something of the life and religious thought of the people who made them,” writes Walter A. Hawley in his book of 1913, Oriental Rugs. “Some seem redolent with the fragrance of flowers, others reflect the spirit of desert wastes and wind-swept steppes. So, too, in the colors and designs of some appear,” Hawley continues, “their effort to commune with the unseen forces of the universe.”

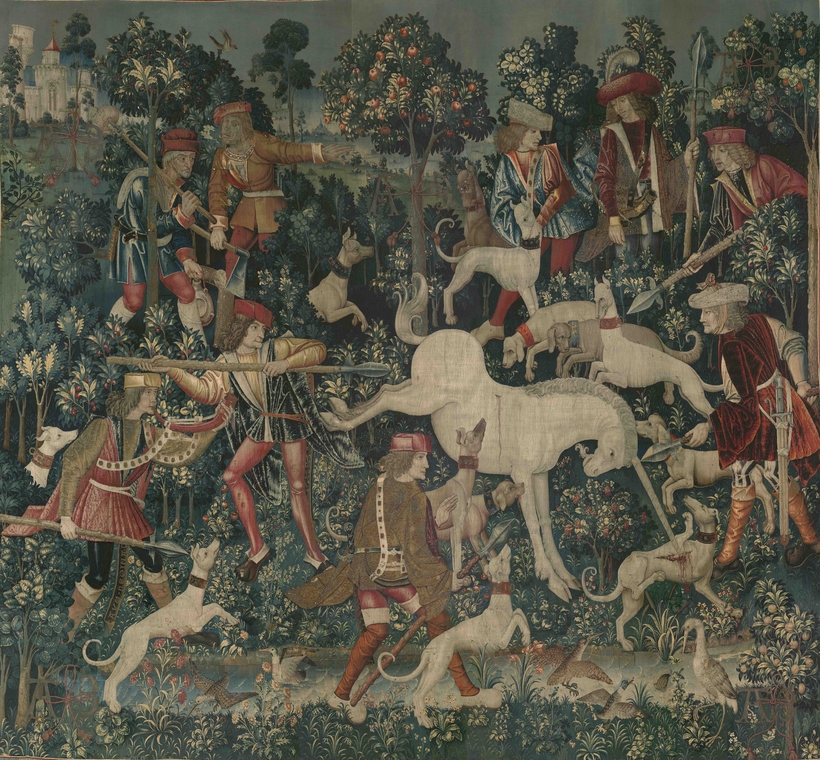

How beautifully put. The unseen forces of the universe are caught up, held in knots or loomed into a flat plane teeming with metaphysical depths. One thinks of the unicorn at the Met’s Cloisters museum in upper Manhattan, collared and corralled in the tapestry The Unicorn in Captivity (1495–1505). The creature symbolizes love, and Christ, and also the weaver’s art of capture.

The unseen forces of the universe are caught up, held in knots or loomed into a flat plane teeming with metaphysical depths.

Woven capture—“woven forms” was the term favored by the late fiber artist Lenore Tawney—has leapt to the foreground in recent decades, with profound work by modern artists now regularly presented in our museums. This month a number of textile-art exhibitions are on view.

From January 21 to 26, the London Antique Rug and Textile Art Fair (LARTA) offers an immersive experience of the textile “scene”—a tight world peopled with scholars, collectors, dealers, and passionate “ruggies.” In Buenos Aires, the phantasmagoric sculptures of Ernesto Neto, who frequently crochets textiles on a huge scale, are part of “Ernesto Neto: Soplo” (until February 16), and in Philadelphia, at the Barnes Foundation, the exhibition “Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miró to Man Ray” will explore the way Cuttoli revived France’s tapestry business by commissioning designs from prominent artists (opening February 23). “Knotting the Space: Aurèlia Muñoz Donation,” in Barcelona until April 1, celebrates the work of the visionary textile sculptress, who pulled totemic power from macramé techniques.

Finally, at the Art Institute of Chicago, “Weaving Beyond the Bauhaus” continues through February 17. Take a look at Ethel Stein’s White Pinwheel (1990). In shades of ecru and beige, not unlike a damask dinner napkin, it’s a playful game of depth perception, a vertiginous corridor that is also a trompe l’oeil expression of infinity.