Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957) was the greatest Wagnerian of his time, as smitten cognoscenti on three continents agreed. The Wagnerian prowess of Toscanini’s artistic heir Riccardo Muti (born 1941) is a memory little known outside Milan, where he led Parsifal and the four “Ring” operas as the longest-serving music director in the history of the Teatro alla Scala (1985–2005). With the overdue release of Die Walküre—the second and most popular segment of the “Ring” cycle—as televised on December 7, 1994, the genie at last escapes the bottle.

I remember Muti’s Götterdämmerung and Parsifal as profoundly imagined, thoroughly realized interpretations, revelatory in detail yet never fussy, tremendous in their sweep. This Walküre confirms such impressions. Call Muti’s Wagner “Italianate” if you insist. His flair for “endless melody” (Wagner’s phrase, coined in his polemic “The Artwork of the Future”) might seem to justify the label. Likewise the singing, free of the growls, groans, snarling, and ad lib shrieks the clashes of the “Ring” so easily trigger. Viewed another way, these qualities merely illustrate a vocal and dramatic ideal built on musical rather than crudely representational values, and that’s not a question of nationality.

A teaser for Die Walküre goes straight to the Ride of the Valkyries, popularized by filmmakers from D. W. Griffiths (Birth of a Nation) to Federico Fellini (8½) to Francis Ford Coppola (Apocalypse Now), to name just a few. In knockout visuals, the camera shows the mythic heaven-storming warrior maidens on horseback, stampeding through the sky above a field of poppies, their swords slashing thin air. But this imagery is ultimately as nothing to the orchestral attack and projection, along with the electricity of eight keyed-up soprano and mezzo soloists grabbing their brief chance.

Pictorially, the Ride is the high point of André Engel and Nicky Rieti’s serviceable though hardly distinguished production. Never mind. There’s plenty to watch in the performances of the players. Plácido Domingo sings Siegmund, hounded by fate, in burnished, thrilling tones. As Siegmund’s long-lost twin Sieglinde, the phenomenal Waltraud Meier channels Garbo even as she etches her ecstasies in liquid fire.

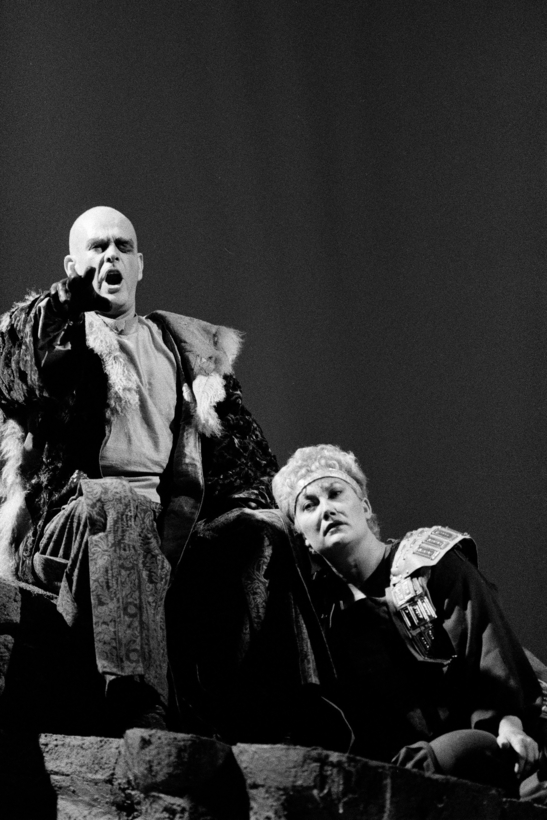

As the twins’ father Wotan, chieftain of the gods, Monte Pedersen displays the power you look for in this part but also a smoothly romantic timbre that approaches revelation. (It doesn’t erase more traditional interpretations, but it works.) In his 40s at the time, Pedersen was to die at the age of 51, having recorded little. What luck to rediscover him here, in such form. Finally, Gabriele Schnaut’s Brünnhilde doesn’t cut your ideal Valkyrie’s athletic figure, but her voice blazes like a beacon, and her lovely face reflects the character’s adolescent mood swings with rare transparency.

Newcomers to the “Ring” with a reading knowledge of Italian may appreciate a chyron that flags pivotal moments in the story. Wagner’s celebrated leitmotifs—his musical signatures for key characters, objects, and ideas—are selectively identified, as well: TEMA DELLA SPADA, (theme of the sword), TEMA DI SIEGFRIED (Siegfried’s theme), TEMA DELL’ENIGMA DEL FATO (known in German and English more simply as the theme of fate), and so on. For subtitles, there are the options of English, Italian, and none.

Die Walküre is available on the streaming service Teatro all Scala TV

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii