I know it’s perhaps odd to begin a memory of my dearest friend, Derek Granger, who died last month at 101, by talking about his homosexuality. Yet, even in the dark days of draconian sex laws in England in the 1950s, when I first met him, and with many men in various closets, he traveled in all sections of society as though being gay were no impediment, as if it was an essential part of his being and quite a nice thing to be, thank you very much, and if it did bother you, you could go fuck yourself.

Derek and I met in the summer of 1958, when we were both working at Granada TV in Manchester. He had been a journalist, then a theater critic for the Financial Times, and he had been poached by Granada to do a job as yet unnamed. I was a trainee floor manager, the person wearing old-fashioned ear “cans,” trying to understand the director’s instructions while navigating bursts of static. I was due to begin at Oxford in September.

I was going to London for what I hoped would be a sleepless weekend and was already on the train when Derek came into the carriage and asked if I minded if he sat opposite. We ordered tea. We’d not really known each other so far.

I’ve never forgotten the four-hour train journey, because that’s when we had our first conversation, and although he was 20 years older, a young junior officer in the Navy in World War II wanting to be involved with television drama now, he seemed sort of the same age, as he did all his life, never old no matter what the years said, always young.

Derek made me feel interesting, which at 18 I wanted to be but was often faking what I thought till I’d figured it out. He was a delight—funny, getting the joke wherever it appeared, serious, sharp, observant, and thoughtful—and had unusual ways of looking at things. We’d meet over the years as both our careers prospered, and I was always happy to see him as well as his life companion and, later, civil partner, the uproarious and irrepressible designer Kenneth Partridge. The two were together for 66 years.

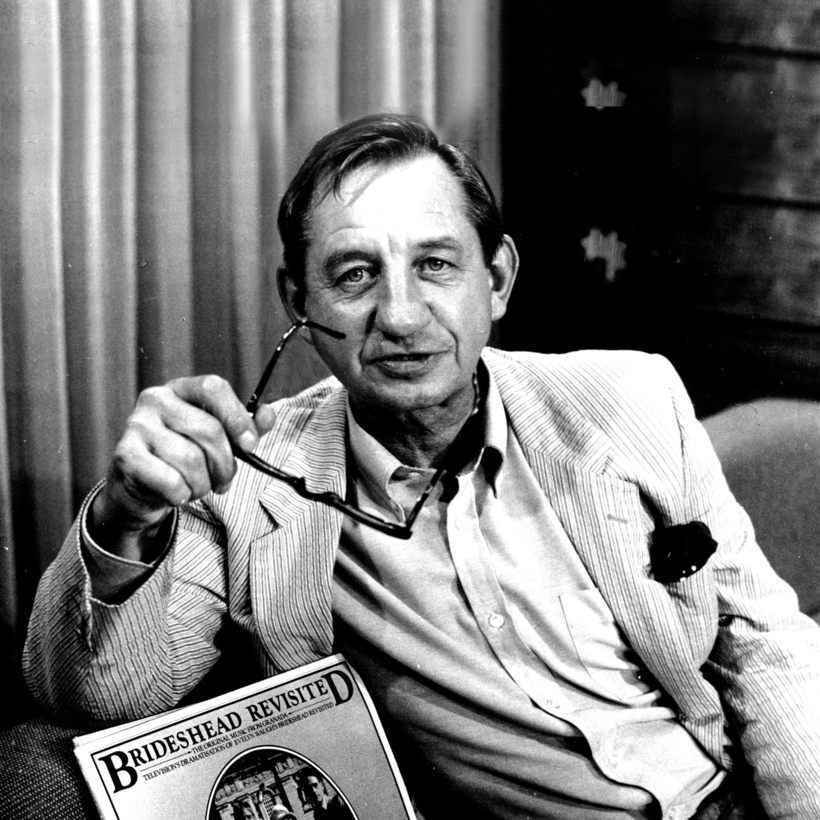

Then, in 1978, 20 years after that train ride, Derek, who had become a producer, offered me my dream project: to direct the TV adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. He and I cast it, and it started filming in Malta, then shot for another five months all over England, before a long-simmering union aggravation burst open and the whole network went on strike for four months, and I couldn’t finish it because of another commitment. Derek and I stayed friends, perhaps closer than before, because the early days of Brideshead Revisited were like lifting a large tree off the ground, and we did it together.

About a month ago, I got an e-mail from Anthony Andrews (Lord Sebastian Flyte) saying he’d recently been to see Derek and that he was getting frail and couldn’t move easily, although his mind was still quick. Derek had asked him if he knew where I was and said that he’d love to see me if I were anywhere around. My wife and I, by happy coincidence, were going to be in London a week or so later, and we made an appointment with Marilyn Jones, Derek’s neighbor, friend, companion, and helper, to come and see him around four o’clock on the afternoon of November 24.

In the few days before we were due to meet, Lisa and I got the coronavirus, and my doctor said no way could we be in a room with Derek, so we scheduled a Zoom.

Derek was lying in a recliner with a warm blanket wrapped around him. His funny face—slightly fleshy nose, broad smile, kind eyes—was the same but distant on the pillow. We reminisced a bit, but his hearing aids fell out every so often, and he’d say to Marilyn, “Can’t hear him.”

At one point I said loudly, “You should have an ear trumpet like Evelyn Waugh used.”

To which he responded, “Ear trumpet? I’d need an ear orchestra.”

I looked at my friend, distant in another part of London, and remembered our train ride of more than half a century earlier, when it had all started. But we’d see each other again next week.

“I love you, Derek.”

“And you too, Michael.”

He died five days later. He was a one-off.

Derek Granger died on November 29, aged 101

Michael Lindsay-Hogg is working on a memoir about the first production of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, which he directed at the Public Theater