“So what are you? A concubine?”

A few years ago, my mother asked me this over the phone. I’d told her that I was in a polyamorous relationship—that the man that I was seeing already had a girlfriend.

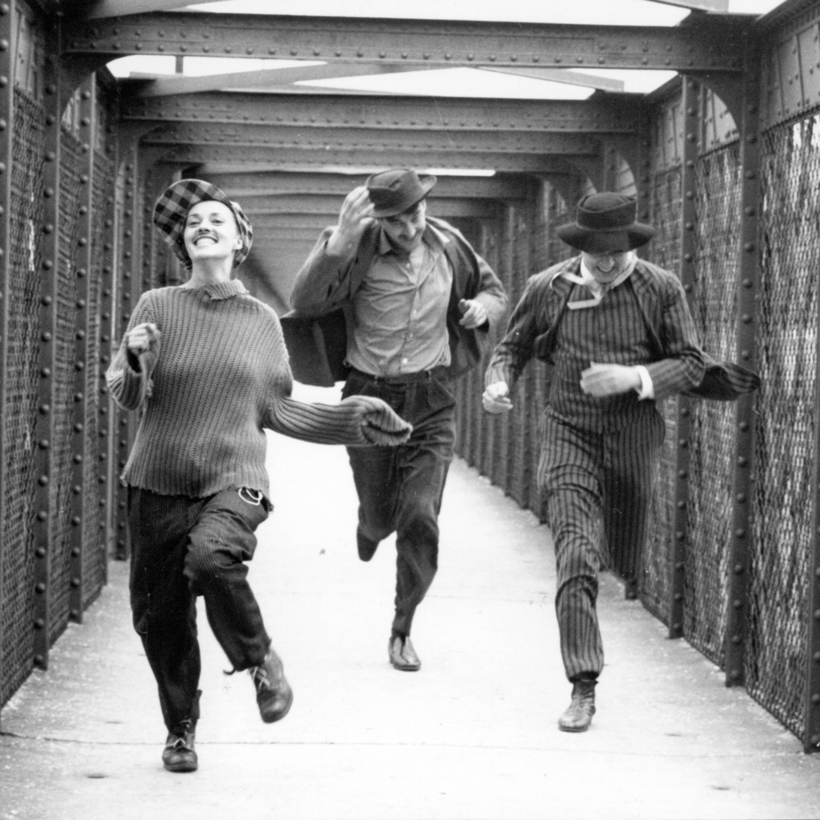

A young woman experimenting with polyamory wonders if she’s discovered the ideal relationship—or is simply settling for second best

“So what are you? A concubine?”

A few years ago, my mother asked me this over the phone. I’d told her that I was in a polyamorous relationship—that the man that I was seeing already had a girlfriend.